Invasive buckthorn is running rampant in northern forests, including those right here in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Curbing the spread of the invasive forms of the species, which include glossy and common buckthorn, is a formidable challenge, but our Husky experts continue to explore and innovate solutions. Their methods encompass everything from natural treatments to herbicide applications.

Researching An Old Problem for Young Forests

Forest science PhD candidate Chris Hohnholt is among Tech researchers investigating countermeasures against the glossy buckthorn invasion. Hohnholt’s research tested the efficacy, ecology, and economics of three glossy buckthorn treatments: hand-pulling, treatment with a glyphosate herbicide, and treatment with a triclopyr herbicide.

“This work began with a question of whether hand-pulling has less impact on the plant community than herbicides,” said Hohnholt. “Our goal isn’t to weigh the potential impacts of a single herbicide; it’s to weigh the potential impacts of all of the control mechanisms.”

Though he is still parsing data from his work, initial observation shows hand removal followed by immediate herbicide treatment creates an effective combination with relatively minimal impact on native plants.

Hand-pulling is a tried-and-true method for battling invasive buckthorn, but the downside to this approach is the physical strain. “It’s not a muscle you go to the gym and work out for,” Hohnholt said.

Root wrenches and other tools can make removal easier. However, larger plants can be difficult, if not impossible, to pull even with an assist from mechanical leverage. In the case of stubborn, well-developed plants, buckthorn can be cut back to stumps—but stumps can regrow over time if no further action is taken.

In addition to using hand removal, Hohnholt experimented with applying two types of herbicide directly and selectively to glossy buckthorn stumps: glyphosate and triclopyr. Glyphosate, a common herbicide used on broadleaf plants that works by blocking an enzyme essential for amino acid production, is often found in forestry, agriculture, and home-use products for weed control. Triclopyr is a selective systemic herbicide used to control woody and broadleaf plants in non-crop areas, pastures, forests and turf. Triclopyr mimics the plant hormone auxin to cause uncontrolled growth that leads to plant death while being less harmful to grasses and conifers.

Hohnholt, currently a curriculum development specialist for Michigan Tech’s Pavlis Honors College, has a background that includes more than three years as a regulator for integrated pest and pesticide management programs for the Department of the Navy. Herbicide applications are regulated by the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), which, Hohnholt explains, dictates that “the label is the law.” This means chemical herbicides must be used according to the directions and applications listed on the label, including the use of personal protective equipment. During his research, he took the extra precaution of only using treatments approved for aquatic applications, although ultimately wet-surface application proved unnecessary for the research.

Buckthorn from a Birds-eye View

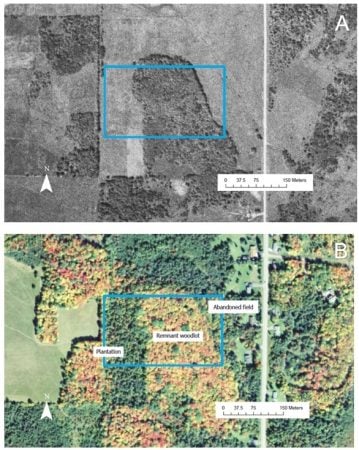

Honholt’s research started in 2021 and focused on a relatively small area on Green Acres Road south of Houghton, Michigan. The property has three distinct types of terrain, including a Scotch pine plantation, an abandoned field, and a northern hardwood forest woodlot in its second-growth stage. Aerial photos show that the remaining hardwood forest on the property has been there since 1938, and likely long before that, though researchers cannot determine the exact age or when buckthorn was introduced. The forest’s resistance to the invasive plant, however, was obvious. When assessing the area, he found that while other types of land on the property had buckthorn growing so thick he could hardly walk or see more than 10 feet through it, the thicker forested areas had far less of the invasive plant.

“There was a third of the buckthorn in the intact forest remnant compared to the rest of the site,” said Hohnholt. “When you cross into the forest canopy, it is as if someone drew a line. You reach a point where the invasive buckthorn growth just stops.”

Within the forest, glossy buckthorn growth pops up where there are gaps in the canopy. In the paper “Glossy buckthorn invasion across three land-use classes in northern Michigan,” published in the Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society, Honholt found that the distance from the edge of the canopy had a significant impact on stopping the growth of glossy buckthorn. He said it’s good news for older forests.

“I would advise land managers to use old area photographs and figure out where they’ve got some older forests. You might want to pay attention to those because you could get on top of it more easily, but also recognize that if you’ve got young forests growing, you might want to develop a long-term strategy of how you’re going to manage that plant,” said Honholt.

The issue is of crucial importance to both personal and industry land owners.

Husky Battles Buckthorn in the Forest Industry

Here in the Upper Peninsula, Tech alumna and CFRES advisory board member Amber Marchel ’19, who earned her Tech MBA®, assists with several properties as the area manager for Lyme Great Lakes Timberlands. The company has addressed two local cases of glossy buckthorn invasion, including one in Ontonagon County, which they believe originated at a now-vacant homestead. Buckthorn growth on the property kept young pine trees from thriving, limiting the property’s productivity. Unmanaged growth along highways bordering the company’s properties is also a cause for concern.

Marchel’s company has addressed the invasive plant through broadcast spraying of herbicide from helicopters.

“This method was unique in that the crew sprayed the site from two different directions, with the hope of hitting the leaves on numerous faces for increased efficacy,” said Marchel. “Apart from treatment, we also have logging crews spray their equipment down before leaving sites believed to house buckthorn to prevent the machines from possibly carrying the infestation elsewhere.”

The approach has allowed pine growth to advance. The company expects that in the long term, the pine canopy will overtake the buckthorn.

Goats Gobble Tasty Invaders

Goats are a surprising but effective tool when it comes to controlling the spread of invasive buckthorn. Easy to transport, able to access dense growth areas where humans and machines can’t easily go, they’re a non-toxic replacement for chemicals used in eradication efforts.

Sigrid Resh, CFRES research assistant professor, says goats can play an important role in buckthorn remediation in the understory. “They eat almost anything, so they’re perfect in those areas where native plants struggle in dense infestations.”

Because goats have expansive digestive tracts, the seeds they ingest don’t germinate after being passed. It’s also helpful that goats trust people and keep to the herd, making them easy to manage. They can shelter for days or weeks at grazing sites.

Goat remediation projects are a key experimental tool for Keweenaw Invasive Species Management Area (KISMA). The organization has been funding goat remediation at Swedetown Mountain Bike and Ski Trails in Calumet, Michigan, for three years under a USDA Forest Service Great Lakes Restoration Initiative in partnership with Swedetown Trails Club and Calumet Township. During their visits, the goats have cleared a four-acre section of buckthorn near the recreation area’s chalet—along with delighting observers.

Invasive Problems, Fungal Solutions

Mushroom soup may seem an unconventional method for combating invasive buckthorn, but that kind of outside-the-box thinking is what led to Abe Stone’s research into fungal preventatives for invasive buckthorn. As an undergraduate studying ecology and evolutionary biology, Stone ’24 used novel cultivation techniques to grow and process globs of the fungus Chondrostereum purpureum – or “SuperPurp,” as he called it – into a spray-on treatment to discourage buckthorn growth.

SuperPurp is a weak forest pathogen commonly known as silverleaf disease. Stone blended a local strain of the cultivated pathogen with water, creating a “mushroom soup” that could be applied to both glossy and common buckthorn plants with a garden-variety sprayer. Though the fungus won’t kill buckthorn on its own, inoculating it with SuperPurp weakens the aggressive invaders – giving native species a chance to rebound.

Though SuperPurp hasn’t been developed for public or commercial use, Stone’s work shows fungal alternatives hold promise. The added benefit is that SuperPurp is native to the region and, when applied judiciously, doesn’t pose a threat to the surrounding ecosystem.

“It is very much a part of the forest ecosystem and has been around for thousands of years,” said Stone, in a Michigan Tech News story about his work. “In its natural state, it only infects trees with significant wounds and wouldn’t wipe out an entire forest. It is merely one of the many actors causing our forests to develop into various types of ecosystems.”

How to Identify Glossy Buckthorn

The first step in removing invasive plants is properly recognizing and identifying them. KISMA, one of 22 cooperative invasive species management areas in Michigan, uses outreach and education to prevent and manage invasive species across land ownership boundaries. KISMA goes beyond invasive species removal, restoring native plants to habitats to add food sources and habitats for pollinators, helping to increase forest ecosystem resiliency by increasing biodiversity.

Two buckthorn varieties are on KISMA’s list of priority terrestrial invasive species. Both glossy buckthorn, Frangula alnus, and common buckthorn, Rhamnus cathartica, are small, woody trees from the Rhamnaceae family. Both are highly invasive and cause a myriad of ecological problems. Glossy buckthorn is especially problematic in wooded areas with soggy soils, lots of human traffic, and a history of land disturbance, but both varieties can tolerate a wide variety of habitats.

Common and glossy buckthorn plants spread rapidly by producing a large number of seeds, suppressing the growth of native shrubs that are important food sources for nesting birds. While buckthorn produces loads of berries, it lacks the protein and fats that native fruit-eating birds require. The plant also doesn’t support native caterpillars that carnivorous birds prefer.

Invasive buckthorn is on KISMA’s priority list, and the organization offers several resources to help identify and remove the plants. Both buckthorn varieties have brown stems that turn gray with age, covered in very prominent white lenticels. Small, five-petaled flowers are green-yellow and grow in clusters. Plants produce numerous black, round, bird-dispersed drupes that are persistent through winter.

Common buckthorn leaves are dark green, oval-shaped, with a toothed margin and veins that bend toward the tip. This variety of buckthorn can be confused with native cherries like pin cherry and chokecherry. Cherries will have two black spots (glands) on the leaf petiole (stem) near the base of the leaf, while buckthorn will not.

Glossy buckthorn leaves are similar to their common relatives, but have a shiny underside and glossy surface that gives the variety its name. Glossy buckthorn is easily confused with dogwood. While glossy buckthorn leaves are shiny on the underside, dogwood leaves are not. Also, dogwood leaves have white strings when torn apart carefully.

The Best Solution for Your Buckthorn Blues

Individual landowners have several options for managing buckthorn—but removing it completely is a different story.

“I don’t think that we’re going to eradicate it. I think it’s a management issue that’s going to boil down to what the landowner wants to do with that piece of property,” said Hohnholt.

For landowners who want to minimize impacts on native plant species, Hohnholt recommends hand-pulling alone as the best management method. Despite his early hypothesis that disturbing the forest floor by yanking out buckthorn would negatively affect local plant life, his work shows no major impacts on the surrounding forest.

The biggest safety precautions when hand-pulling are for the eradicators’ physical well-being.

“Mental fatigue starts to come in after about 30 minutes, and then you start to take shortcuts to pull it out,” said Hohnholt. “That’s fine 99 times out of 100, but at some point, you get the angle wrong and end up talking to your chiropractor about it.”

To maximize the effect of all that hard labor, buckthorn plants are best yanked before berries start to form. Dropped berries spread seeds that lead to more plants. Once removed from the ground, inverting the plants’ root system to die will eventually kill the rest of the plant.

If the plants have seeds when pulled, KISMA recommends burning the branches where they are removed to contain the seed and prevent additional spread, but only where burning is permitted and in conditions where it is safe to do so. On-site burning, when it’s safe and legal to do so, also helps keep the area clear for easier access. If branches with seed need to be moved off-site, it’s best to use tarps to contain the seeds that fall during transportation.

Hohnholt’s glossy buckthorn research showed that the most effective treatment for larger plants is to cut back as much as possible and immediately apply herbicide directly to the stump.

“I found some literature on other invasive shrub species that recommends getting in there and treating those stumps with the herbicide within 60 seconds. When we did this during our research, it proved to be very effective. If you’re applying it with a paintbrush, you’re not going to get it on the surrounding plants, which makes it an amazing solution,” he said.

Deciding whether and what type of herbicide to use depends on where the buckthorn is located and how mature it is.

“Glyphosate requires a lot of active growth to be effective, so the plants need to be receiving a lot of sunlight for that to happen. If they’re overtopped by forest canopy, it seems as though it just wasn’t quite as effective,” said Honholt. “The triclopyr labeled for forest use, though, it really does a good job of targeting woody species. You’d hit the glossy buckthorn with that stuff, and it was just gone.”

Though seedlings have returned in areas Hohnholt treated with triclopyr, the mature shrubs have shown no signs of life two years after a single year’s treatment. That being said, he views herbicides as a “tool in the toolbox” of invasive species management, not necessarily the recommended primary method, due to environmental and ecological concerns.

For plants too large to pull by hand, KISMA recommends a smothering method that involves cutting the plant back, then tying or zip-tying a plastic sheet or bag over the stump and securing it with soil or rocks. This smothering technique will prevent stump sprouting and kill the root mass, and eliminate herbicide use.

Those looking for additional guidance or interested in helping combat invasive species in the area can reach out to KISMA at kisma.up@gmail.com or 906-487-1139.

About the College of Forest Resources and Environmental Science

Michigan Tech’s College of Forest Resources and Environmental Science brings students, faculty, and researchers together to measure, map, model, analyze, and deploy solutions. The College offers six bachelor’s degrees in forestry, wildlife ecology and conservation, applied ecology and environmental science, natural resources management, sustainable bioproducts, and environmental science and sustainability. We offer graduate degrees in applied ecology, forest ecology and management, forest molecular genetics and biotechnology, and forest science.

Questions? Contact us at forest@mtu.edu. Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn for the latest happenings.