Michigan Technological University’s ingenious little vehicle took first place and nabbed honors for creativity at the North Central Region Chem-E-Car Competition, held April 21 at the University of Akron. The event is sponsored by the American Institute of Chemical Engineers and Chevron.

Chem-E-Car entrants build small cars, about the size of a shoebox, and power them using chemical reactions. About an hour before the competition, they are told the length of the course and the weight of the payload. Then, they configure their vehicles to roll as close as they can to the finish line.

This year, the course was 71 feet long, and the payload was 300 grams. The Michigan Tech car, named “Paradise Lost,” halted just six inches shy of the finish line. The next-closest competitor, Purdue University, was 11 inches away.

“We had a fantastic weekend,” said Ross Koepke, team leader and a junior majoring in chemical engineering. “We put a lot of time in before the competition, and it paid off. Coming away with these awards is outstanding.”

For a few moments, though, it was touch and go. “One of our pressure regulators locked closed about 30 seconds before our car was supposed to run,” Koepke said. “We would have had to scratch, but the team really came together, got the tools we needed, and fixed the problem. Not only were we able to compete, but also that was the round that won us the competition.”

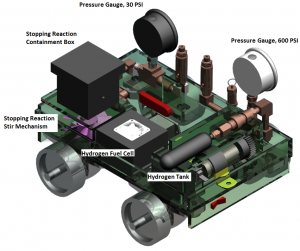

The car relied on two chemical systems. Electric power was provided by a hydrogen fuel cell that drew hydrogen gas from a metal hydride cylinder. “Hydrogen molecules are so small they can migrate into metals and form an alloy,” Koepke said. “What this allowed us to do was store more hydrogen in a smaller volume at less pressure. Last year’s Chem-E-Car team developed this technology, and it was a key part of our success.”

A different, two-part chemical reaction stopped the car. The first part created chemicals that turned a solution deep purple. The second reaction removed those purple chemicals, keeping the solution transparent.

A photodiode kept an eye on the solution, and as soon as the solution darkened to purple, the photodiode flipped a switch to stop the motor. Timing the appearance of the purple was key to making the car travel the length of the course.

Yes, Koepke said, it’s pretty cool, but that’s only part of the story. When the team was developing the car, it wasn’t stopping consistently, because the chemicals weren’t dispersed evenly in the solution. “So we installed a stirring mechanism,” he said. “There were two magnets, one inside the reaction vessel and one beneath it. The one beneath is connected to a modified computer fan.

“Basically, the fan would spin the magnet outside, which would spin the magnet inside, which stirred the solution.” Soon they had their car stopping on a dime.

However, they earned their creativity prize for something other than their creative use of chemicals. “We had an obsessive focus on safety,” Koepke said. The team replaced chemicals that posed a hazard with very benign substances, like ascorbic acid, or vitamin C. But they kept their beefed-up shielding anyway to emphasize the importance of safety.

The team’s faculty advisor, Tom Co, was not surprised that the Tech team took first. “Before they even left for the contest I considered them winners because of their teamwork and their persistence in getting quality results,” said Co, an associate professor of chemical engineering. “I was confident that they would do well. We are all very proud of them.”

But how did they come to name their vehicle after an epic 17th century poem? The team just liked the sound of it, Koepke said. But none of them anticipated what they would see as they entered the awards banquet.

“We found a copy of Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’ in the foyer,” he said. “It was the only book there.”

The team will attend the 2012 AIChE Chem-E-Car National Competition set for Oct. 28 in Pittsburgh. In addition to Koepke, the team members are Christian Dale, Ben Veenstra, David Hutchison, Justin Levande and Ben Markel.

Read More