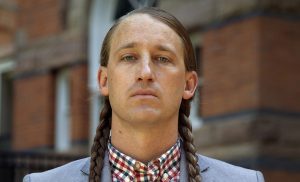

HOUGHTON — Dylan Miner identifies strongly with his Wiisaakodewinini, or Métis, ancestors — a people of mixed indigenous and European ancestry who have lived in both Canada and the United States. Since his own family ancestors lived on Drummond Island in Lake Huron, water, land and settler colonialism are important elements of his art, his activism and his scholarship and teaching.

HOUGHTON — Dylan Miner identifies strongly with his Wiisaakodewinini, or Métis, ancestors — a people of mixed indigenous and European ancestry who have lived in both Canada and the United States. Since his own family ancestors lived on Drummond Island in Lake Huron, water, land and settler colonialism are important elements of his art, his activism and his scholarship and teaching.

Miner is Director of American Indian and Indigenous Studies, and Associate Professor in the Residential College in the Arts and Humanities at Michigan State University. He sits on the Michigan Indian Education Council and is a founding member of the Justseeds artists collective. Miner holds a PhD from The University of New Mexico and has published more than sixty journal articles, book chapters, critical essays, and encyclopedia entries.

Presenting himself humbly as a learner of indigenous languages, Miner introduced himself to the audience at Michigan Tech in two of them.

In addition to expressing his environmental concerns, Miner demonstrated how he uses art on social media to call attention to socio-political injustices against indigenous people. He also displayed artwork created by one of his own Métis ancestors.

Bonnie Peterson, a local artist who attended Miner’s talk, was impressed by his use of art to communicate messages on social media.

“His work turns the patriarchial power establishment on its head,” Peterson said. “He reacts to current events by creating thoughtful, compelling images immediately, and freely distributing them on social media. His image ‘no pipelines in/under the great lakes’ is especially salient because of the threats to Great Lakes from oil spills, and also robbing the Great Lakes of water.”

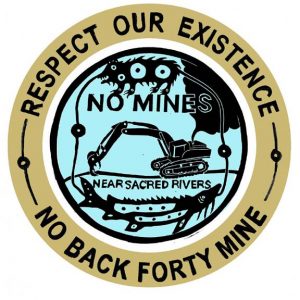

Miner also mentioned how he altered some of his images after talking with people directly impacted by extractive industries. He noted as an example his discussions with Menominee tribal activists fighting Aquila’s Back 40 mining project, which could destroy indigenous sacred sites and impact the Menominee River. He changed his original design to include the Menominee ancestral bear and the sturgeon.

Miner also mentioned how he altered some of his images after talking with people directly impacted by extractive industries. He noted as an example his discussions with Menominee tribal activists fighting Aquila’s Back 40 mining project, which could destroy indigenous sacred sites and impact the Menominee River. He changed his original design to include the Menominee ancestral bear and the sturgeon.

Collaboration is important in Miner’s work. He spoke about working with others to create projects that combine creative activities with environmental consciousness or stewardship, such as a traditional building of a birch bark canoe, an urban sugar bush, Native kids riding bikes and his recent Drummond Island reclamation project.

According to Lisa Gordillo, curator of the exhibit, “Miner’s work reimagines the landscape through digitally adjusted images that counterbalance cyanotype and  contemporary processes. Cyanotype is an antiquated photographic method developed in 1842, the same year that the Treaty of La Pointe ceded Anishinaabeg Lands in the western Upper Peninsula and northeastern Wisconsin. The artist’s use of cyanotype builds a physical and conceptual connection to colonial Land expropriation, capitalist expansion, and the development of new image-making technologies. Our viewpoint is stirred as Miner distorts his original images, applying pigments, minerals, and smoke, shifting their size and scale.”

contemporary processes. Cyanotype is an antiquated photographic method developed in 1842, the same year that the Treaty of La Pointe ceded Anishinaabeg Lands in the western Upper Peninsula and northeastern Wisconsin. The artist’s use of cyanotype builds a physical and conceptual connection to colonial Land expropriation, capitalist expansion, and the development of new image-making technologies. Our viewpoint is stirred as Miner distorts his original images, applying pigments, minerals, and smoke, shifting their size and scale.”

Local artist Joyce Koskenmaki, who attended Miner’s talk and visited the exhibit, commented on the cyanotype images.

“Dylan’s cyanotype images at the Rosza are beautiful,” Koskenmaki said. “His work and his talk speak to me about art for poor people: art that can be done with simple materials, and art with a message. I felt inspired.”

Miguel Levy, artist and Michigan Tech professor of physics, who is active in the local Indigenous Peoples’ Day Campaign group, said he was especially impressed by Miner’s connections between art and indigenous resistance.

Levy noted, “Regarding Dylan Miner’s talk, I found the connections he made during his talk quite illuminating: [between] the social and political dimensions of his art, between indigenous culture and resistance to environmental devastation, and between the revolutionary potential of the indigenous tradition and its points of coincidence with the anti-hierarchical and anti-capitalist traditions of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) labor union.”

Emily Shaw, Michigan Tech PhD student in environmental engineering, who introduced Miner, told Keweenaw Now Miner’s stories and connections inspired her to ask herself questions.

“So often we view art and science as unrelated but making art and doing science are processes that require us to ask ourselves what do we know and what skills do I have that can contribute to our learning? Dylan opened with those questions and shared the story of his art, weaving connections between land abuses, indigenous rights, and labor unions. I left inspired to make such connections in my work as a scientist.”

Dylan Miner has also authored and edited several limited-edition books // booklets. His book Creating Aztlán: Chicano Art, Indigenous Sovereignty, and Lowriding Across Turtle Island was published in 2014 by the University of Arizona Press. In 2010, he was awarded an Artist Leadership Fellowship through the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian. He has been an artist-in-residence at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, École supérieure des beaux-arts in Nantes, Klondike Institute of Art and Culture, Rabbit Island, and The Santa Fe Art Institute.

Learn about Dylan Minor’s projects. Thanks to Bonnie Peterson for this link.

Learn more about Dylan Miner and the art he shares on justseeds.org.

By Michele Bourdieu

With videos and photos by Allan Baker for Keweenaw Now