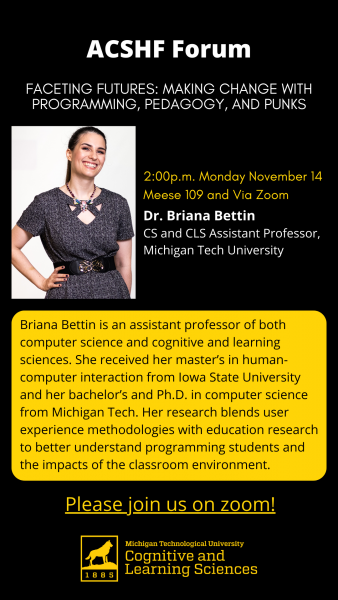

The Department of Cognitive and Learning Sciences will host CS and CLS Assistant Professor Dr. Briana Bettin at the next Applied Cognitive Science and Human Factors forum Monday (November 14) from 2:00pm to 3:00pm in Meese 109 and via Zoom.

Briana Bettin is an assistant professor of both computer science and cognitive and learning sciences. She received her master’s in human-computer interaction from Iowa State University and her bachelor’s and Ph.D. in computer science from Michigan Tech. Her research blends user experience methodologies with education research to better understand programming students and the impacts of the classroom environment.

Abstract: Our increasingly digital society requires citizens to effectively communicate about and with computing technologies to thrive. All too often, these technologies impacting our lives are suggested to be apolitical, while details of their design – including their limitations – are obfuscated, ignored, or considered inevitable. Navigating the world of computing and digital landscapes already poses a variety of challenges which can make new obstacles, “glitches”, and outcomes feel insurmountable. Coupled with stereotypical notions suggesting increased difficulty and limited societal impacts of computing and programming, learners of all ages and skills can easily become frustrated and discouraged from learning skills and topics necessary for today’s society.

This talk explores the need for and explorations toward increasing awareness, understanding, and agency toward computing as a crucial component of modern society. From learning to code to understanding data collection, opportunities abound to transform learner relationships with computing material. Empowering learners to communicate confidently about computing gives them the power through language to begin critically analyzing and reimagining these technologies. With technology demystified and new pathways opened, learners may feel more capable to advocate for and/or create change. This approach to agency formation draws from theories of “punk DIY subculture”, positing that “punk programmers” might be defined as individuals who recognize faulty societal norms in technology design, and “DIY” approaches to subvert them. By toppling barriers to entry, giving learners a voice, and inspiring agency, more “punk programming pedagogy” may play a key part in reimagining the multifaceted possibilities of our sociotechnical futures.