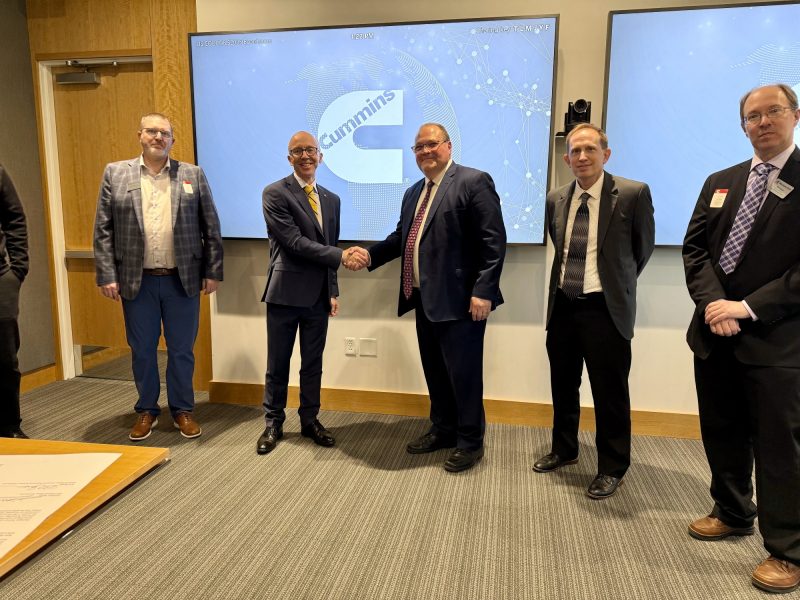

Cummins’ Chief Technical Officer, Jonathan (Jon) Wood stands next to MTU’s Vice President for Global Campus and Corporate Partnerships, David Lawrence at the Cummins’ Corporate Fellowship signing ceremony. Surrounding them are various leaders and representatives of both Cummins and Michigan Tech.

On Friday, May 9, 2025, the MTU Global Campus team, and a cohort of esteemed professors, program directors, and other leaders from Michigan Technological University travelled to Columbus, Indiana.

Their goal: spending a very full day at the Cummins Corporate Headquarters. While there, they toured the impressive facilities, attended a signing ceremony for the Corporate Education Fellowship Program, and took in an alumni event.

Cummins Inc., a global power solutions leader, comprises five business segments: Components, Engine, Distribution, Power Systems, and Accelera by Cummins. These segments are supported by its global manufacturing and extensive service and support network, skilled workforce, and vast technological expertise. Cummins is dedicated to its Destination Zero strategy. The company has a commitment to sustainability and to helping its customers successfully navigate the energy transition with its broad portfolio of products. Cummins, which has approximately 69,900 employees, earned $3.9 billion on sales of $34.1 billion in 2024. (See how Cummins is leading the world toward a future of smarter, cleaner power.)

For all these reasons, Cummins is an ideal partner for Michigan Tech’s Corporate Fellowship Program.

The Corporate Education Fellowship supports Cummins’ employees in their pursuit of graduate education through MTU’s Global Campus. In short, eligible employees of Cummins will receive fellowships to enroll in one of Tech’s online graduate certificates or master’s degree programs. Thus, the fellowship enables the company’s employees to acquire industry-needed skills, follow areas of professional interest, and meet the diverse needs of their stakeholders.

Experiencing Cummins’ Rich History

The eventful day began with a tour of the Cummins Technical Center. This tour provided a view into the company’s operations, their special projects, and recent technological developments.

Next, the group viewed Cummins’ Corporate Office Building. This building’s lobby, which includes the company’s museum, features several impressive display cases documenting the company’s rich history and technological achievements.

For instance, the group enjoyed one wall featuring a mounted 1989 Ram D250 truck with a Cummins’ engine. This display highlighted the company’s long partnership with Ram for producing high-powered, on-highway pickup trucks. In fact, this 1989 truck began as a 1988 Model Year D250, built at Chrysler’s Warren Truck Assembly Plant in Detroit, Mich.

They also witnessed other impressive company firsts. For instance, one standout was Cummins’ red and yellow #28 Diesel Special IndyCar. Built to take advantage of the new 1952 Indy 500 race rules permitting four-cycle diesel engines, this experimental car featured a 6.6 inline-six, 380-horsepower diesel engine. At the time, in fact, it was the first turbocharged Indy racer!

Also, many were fascinated by the exploded engine installation. Strikingly merging art and technology, this sculpture deconstructs Cummins’ NTC-400 Big Cam into more than 500 unique parts suspended in midair. Thus, it celebrates both the achievement–and wonder–of Cummins’ technology. In the 1980s, the NTC-400 Big Cam was the company’s largest diesel engine. Another fact. The sculpture was designed by Rudolphe de Harake and Associates, but it was Cummins’ employees who painstakingly put it together in 1985.

Signing the Fellowship Agreement

After this tour, the group attended lunch and then the formal signing ceremony. This second event solidified the Corporate Education Partnership agreement between Michigan Technological University and Cummins.

David Lawrence, Vice President for Global Campus and corporate partnerships; Rick Berkey, Director of Global Campus; and Will Cantrell, Associate Provost and Dean of the Graduate School represented for Michigan Tech. Also attending for MTU were Andrew Barnard, Jason Blough, Jin Choi, Jeff Naber, Brian Hannon, Nagesh Hatti, and Rob Waara.

Representing Cummins were Jonathan (Jon) Wood, Chief Technical Officer; Bob Sharpe, Executive Director, Enterprise Engineering Solutions; and Marc Greca, Technical Product Development Excellence Leader. Other members of the Global Campus team and several leaders from both organizations were also in attendance.

At the ceremony, Jonathan Wood, Bob Sharpe, David Lawrence, and Will Cantrell all spoke to the importance of continued learning and making advanced education attainable for employees.

On the fellowship program, Bob Sharpe, Executive Director, Enterprise Engineering Solutions, said, “We set up this program with Michigan Tech to leverage the numerous courses, certificate programs, and graduate programs focused on key skills and capabilities that we know Cummins needs for the future.”

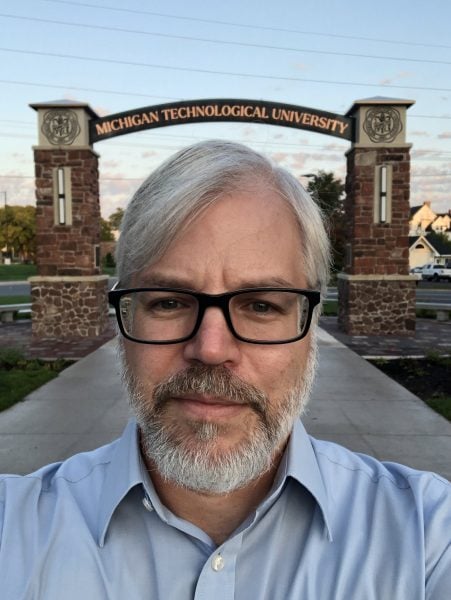

In addition, Sharpe confirmed the preparedness of MTU graduates. “Michigan Tech delivers excellent research in our industry and, even more importantly, develops people with strong practical and hands-on engineering experience. These engineers arrive ready to hit the ground running and deliver great technical work here at Cummins.”

Further Touring and Then Networking with Alumni

After the formalities, the group visited Cummins’ impressive Fuel Systems Operations manufacturing facility. Armed with all the necessary safety equipment, they were privileged to witness the precise work that goes into creating new technologies.

In fact, this branch of the company, which has a very broad presence in the market, offers fuel system technologies for various engine applications. For instance, they produce and remanufacture both unit injectors and common rail systems. Thus, they support engines ranging from 6 to 78 liters. As well, they offer fuel system control modules that work with Electronic Control Modules (ECMs) to optimize fuel delivery, reduce emissions, and improve fuel economy across different fuel types. Learn more about Cummins’ fuel systems.

Finally, the group ended their day with a well-attended Michigan Tech Alumni Gathering. Close to 40 MTU Alumni joined the Michigan Tech and Cummins group. The gathering was an opportunity for MTU and Cummins leaders to network as well as engage with fellow Huskies. And, even better, there was cake!

Collaborating and Growing with a Global, Respected Leader

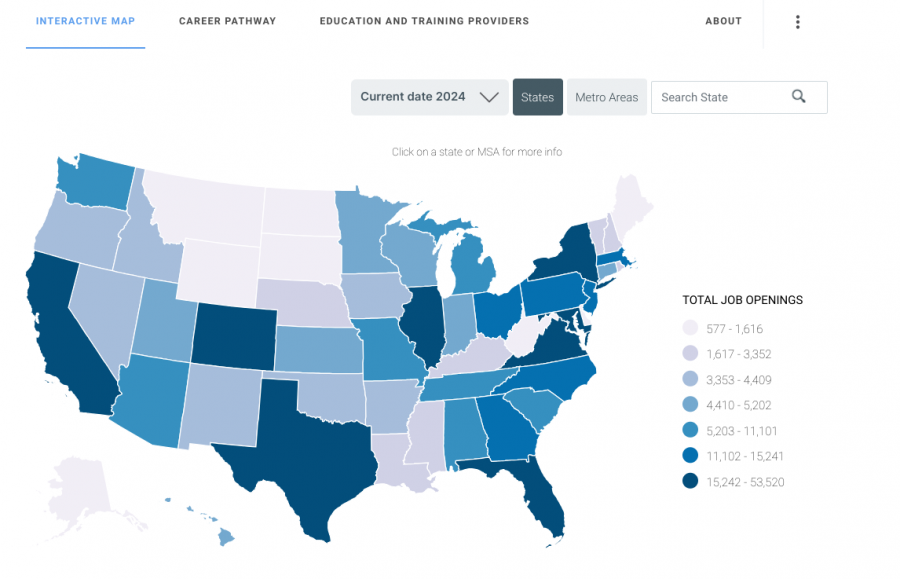

This fellowship program is crucial to Global Campus’s mission of building relationships between academia and industry. It is also central to the objectives of making quality online education more accessible to adult learners and of helping professionals advance and grow with their workplaces.

Overall, the signing and the tour marked yet another milestone in Michigan Tech’s long history of collaborating with future-forward companies that are tackling pressing technological challenges in electricity, power generation, and mobility.

Michigan Technological University looks forward to continuing to collaborate with Cummins and to helping grow its success.

(Shelly Galliah would like to thank Lauren Odem, Executive Assistant to VP David Lawrence, for her superb notes and research.)