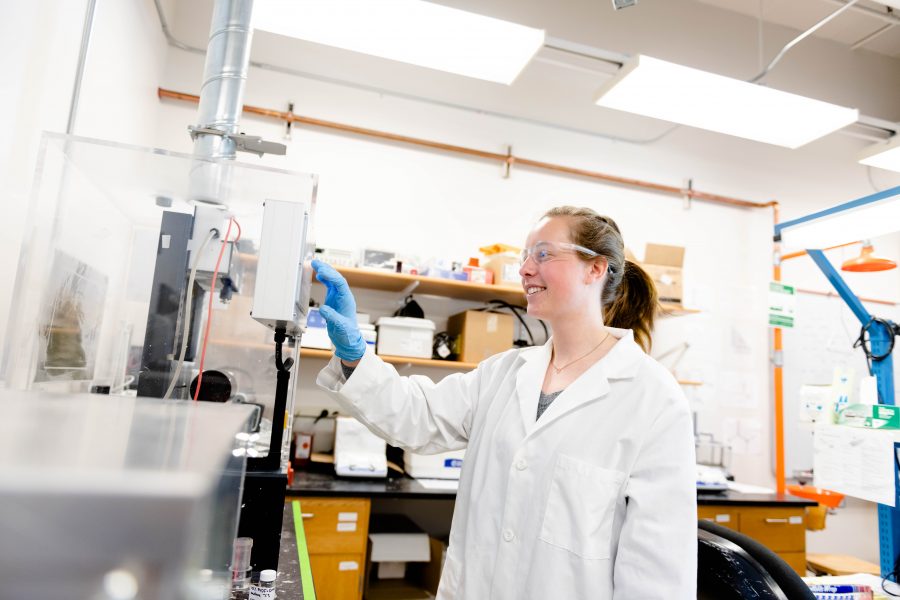

Guest Blog: Life in the Lab: Biomedical engineering student Carolynn Que, explains how one hallway conversation changed her career.

I saw an opportunity when my course instructor for Micro- and Nanotechnologies took us on a tour of her lab. The lab was small, but she was proud of it, and I was keenly interested in what she was working on. I told myself that the next day in class, I would ask to join her research group.

I chickened out for two months. Then I happened to run into her in the hallway one day. It was just the two of us and I mustered some courage, counted to three and blurted out the question. I flushed immediately thinking about how clumsy it sounded and patiently awaited her refusal. To my surprise, it never came. Instead she casually agreed to meet with me to discuss a potential project. My first thoughts were that she must be mistaking me with someone else; I had two classes with her and she had to know I’m not at the top of my class. I think she did know but Dr. Smitha Rao gave me a chance — and I haven’t looked back since.

After jumping through the necessary hoops and following all protocols to become certified to work in the lab, I found myself responsible for creating polymer solutions using various combinations of solvents and polymers such as polycaprolactone (PCL), polyvinylidene (PVDF) and polyaniline (PANI).

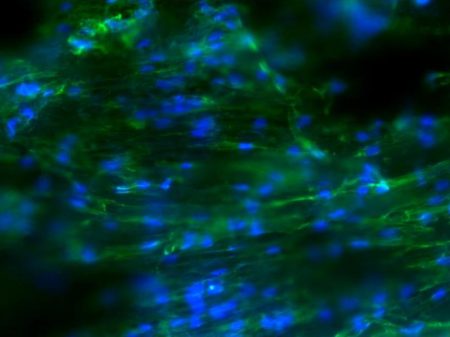

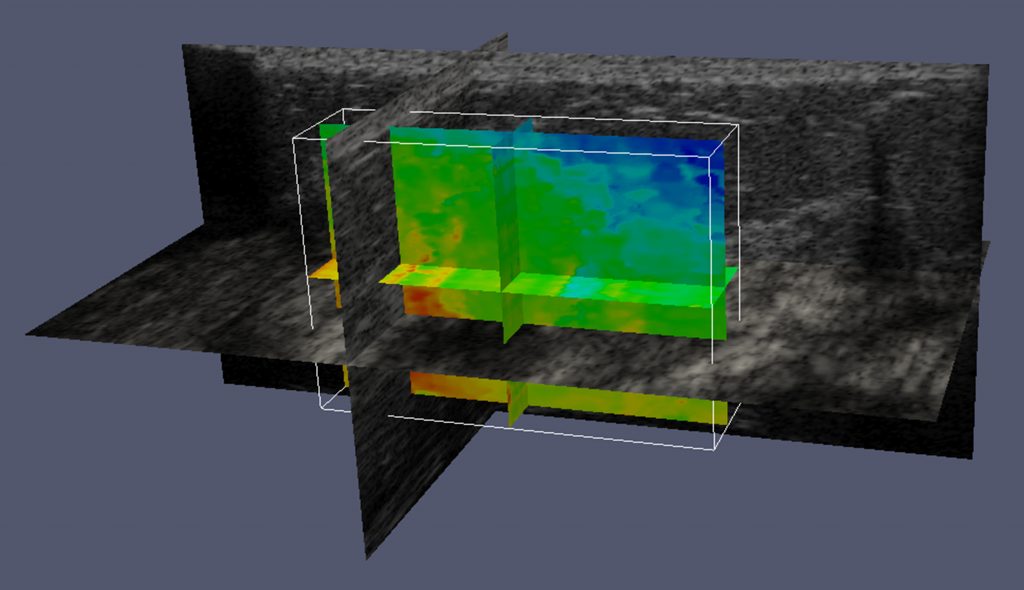

Using these solutions, I fabricate nanofibers using a method known as electrospinning. I change the morphologies of the nanofibers by playing around with the voltage and other parameters. I use these nanofibers as scaffolds, seed cells onto them and monitor cell proliferation and growth, which tells me how the cells behave on the scaffolds and helps me figure out ideal wound dressing parameters. The end goal is that one day this technology will expedite the healing process of diabetic foot ulcers or burn wounds.

While characterizing the fibers, I have learned how to use several facilities and devices. This includes a dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) machine for tensile testing in a temperature-controlled environment, a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) used in nanoscale imaging, ultraviolet-visible and Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy for compositional analysis, brightfield and fluorescent imaging. Not to mention the cell culture experience I gained working with several cell lines from cardio myoblasts and adult human fibroblasts to breast epithelial cells of varying malignancies.

The work I do in the lab builds on coursework. Working in the lab helped me understand my coursework better because I could relate it to real-life applications.

And I’m a published author. I am a co-author on a paper published in Materialia with others in the works.

Working in the lab has taught me how to use my resources to solve real problems in need of real solutions, whether it be via poring over existing literature or seeking the knowledge of peers and faculty. It is okay not to know everything, but lab work gave me the confidence to learn and better myself daily. It has also taught me to accept outcomes and results as they are — I may not like them, I may not have expected them, but things are what they are, and I will find a use for them or modify experiments to achieve better outcomes.

Working in the lab restored my confidence in myself and helped me realize GPA is just a number. It’s something I would highly recommend to any student.

Editor’s note: Carolyn earned her Bachelors and Master’s in Biomedical Engineering at Michigan Tech, and accepted a position as an associate scientist at Regeneron, in New York.