The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects a 12% growth in manufacturing engineering jobs through 2033, indicating strong demand for professionals with these skills. And many of these jobs will be derived from the advanced manufacturing of Industry 4.0.

Advanced manufacturing is the broad, encompassing term for the integration of innovative technologies, automation, cyber-physical systems, data analytics, and advanced materials into traditional manufacturing processes. One main goal of advanced manufacturing is improving products and processes in the manufacturing sector. Another is increasing efficiency and flexibility across the entire production lifecycle.

Both of these objectives are crucial to reshoring American manufacturing.

Take automation, for example. Automating processes reduces labor costs and makes industries more competitive, offsetting the incentive to outsource. Modern technologies also enable higher-quality, lower-defect products. This precision is especially important to high-tech industries that the U.S. is known and respected for: automotive, aerospace, defense, pharmaceuticals, and medical equipment and devices. Advanced manufacturing also supports innovation ecosystems by encouraging creativity through Research and Development (R & D), prototyping, and customization.

And then there are responses to global disruptions (COVID-19) and geopolitical tensions. Advanced manufacturing, better able to support local, just-in-time production, also helps make the U.S. supply chain more resilient.

Because of all its benefits, it is clear that advanced manufacturing is crucial to the growth and sustainability of American industries. Or to put in another way, to reshore US manufacturing while carefully managing labor costs and operational expenses, companies must make significant investments in advanced manufacturing.

Investments in Advanced Manufacturing Accelerate

The benefits of advanced manufacturing are clear. A 2023 Deloitte report indicated that AI-driven automation could reduce operational costs by up to 30% and increase productivity by 20-25%. Similarly, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) emphasized that embracing advanced manufacturing is essential for U.S. businesses to stay competitive while building resilient domestic supply chains.

Admittedly, certain sectors have long been poised for advanced manufacturing. For instance, the semiconductor industry has invested heavily in both AI and automation. On April 15, 2025, Nvidia made a promising announcement. For the first time ever, it would produce its AI supercomputers and Blackwell chips in the U.S. To meet this goal, it will invest up to $500 billion over the next four years while partnering with local suppliers, foundries, and data center builders. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) is putting $100 and Intel are also expanding domestic chip production.

These commitments mean that a large part of the computational power required for driving advanced manufacturing—that for robotics, predictive maintenance, or AI-driven production optimization—will be increasingly available on U.S. soil. This availability will support “smart factories” in America while helping to build the digital backbone of the United States.

But it’s not just semiconductor companies that are putting big dollars behind advanced manufacturing in the United States. For instance, Stellantis recently announced a $5 billion investment in its US manufacturing network. This plan includes re-opening its Belvidere, Illinois plant. Similarly, Kimberly-Clark has committed to expanding its U.S. operations, which includes a new advanced facility in Warren, Ohio. And closer to MTU’s home, Corning’s upcoming expansion of its Michigan manufacturing facility will mean 400 new high-paying advanced manufacturing jobs.

Advanced Manufacturing Requires a Highly Skilled Workforce

All of these examples across various industries underscore the critical role of advanced manufacturing in enhancing efficiency, reducing operational costs, and mitigating supply chain risks. These effects are pivotal to revitalizing domestic manufacturing in the era of Industry 4.0.

However, supporting advanced manufacturing goes far beyond building cool things and adopting new technologies. Companies must also put money into their workforces, training employees of all levels in advanced manufacturing techniques, AI, and robotics. Creating a U.S.-based ecosystem, then, that supports automated, lean, high-output production begins with this most important resource: PEOPLE.

Admittedly, low-skill jobs will be lost to AI and automation. But as industries incorporate new technologies, there will be a demand for high-skill occupations in engineering, software, and data science. For instance, when it comes to technical and engineering roles, companies will need engineers specializing in mechatronics, materials science, and additive manufacturing. To manage digitization and data, they will require more industrial data scientists, automation and controls systems engineers, and cybersecurity analysts.

Also, to troubleshoot automated and computer-controlled systems, companies must bring on additional robotics technicians and quality systems analysts. And of course, supply chain analysts must be on hand to manage the just-in-time inventory while mitigating possible disruptions. In other words, advanced manufacturing requires a highly skilled workforce composed of specialists and innovators from various fields.

Examples of MTU Programs that Support Industry 4.0 Manufacturing

Several programs at Michigan Tech, many of them interdisciplinary, reflect the university’s commitment to integrating advanced manufacturing concepts into its engineering education.

Thus, they prepare students for the evolving demands of manufacturing in Industry 4.0.

These include MTU’s bachelor’s degrees in Mechanical Engineering Technology, Mechatronics, and Robotics Engineering.

MTU also has specific minors directly related to manufacturing. For instance, the university’s Manufacturing Minor has intensive coursework related to machining processes, design with plastics, micromanufacturing, metrology, metal casting, robotics, and mechatronics. And MTU’s Manufacturing Systems Minor focuses on manufacturing fundamentals and automated systems. Courses cover topics such as programmable logic controllers, simulation modeling, and discrete sequential controls. Complementing various engineering majors, this minor enhances students’ understanding of manufacturing operations and automation.

And through the Global Campus, Michigan Tech offers several online graduate certificates relevant to advanced manufacturing and its associated challenges. These include 9-credit programs in Manufacturing Engineering, Quality Engineering, Foundations of Cybersecurity, and Safety and Security of Autonomous Cyber-Physical Systems

Advanced Manufacturing Graduate Programs at MTU

In addition, MTU’s Department of Manufacturing and Mechanical Engineering Technology has respected graduate degrees in manufacturing engineering. These programs are some of the few available in the United States. That is, as of 2025, there are only 75 industrial and manufacturing grad programs in the United States. And only 25 of these are available online.

MTU’s programs are not only unique, but also practical. They are created and taught by manufacturing engineers with decades of on-the-job experience from several industries.

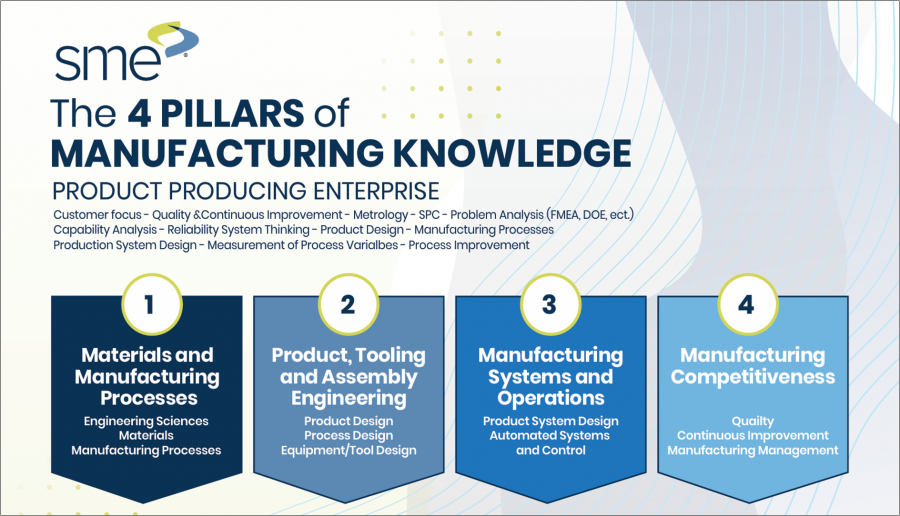

And their up-to-date curriculum is also based on The Society of Manufacturing Engineers’ Four Pillars of Manufacturing Knowledge.

In particular, MMET’s unique programs focus on the fourth pillar–Manufacturing Competitiveness–which is at the hub of smart manufacturing, modeling, simulation, sustainability, additive manufacturing, and advanced materials.

As well, the program also strongly emphasizes the third pillar, Manufacturing Systems and Operations, which includes the two key areas of Production System Design and Industry 4.0 and Automated Systems. Coursework covers Manufacturing System Design, Planning/Plant Layout, Human Factors, Environmental Sustainability, and Safety Production.

Furthermore, the program also supports several of the key knowledge areas that are integral to supporting advanced manufacturing: smart manufacturing, modeling and simulation, sustainability and additive manufacturing, advanced materials, and leadership.

Coursework Designed for Advanced Manufacturing and Industry 4.0

In fact, several core courses address these knowledge areas while preparing students for the specific challenges of as well as leadership roles in advanced manufacturing. Take Industry 4.0 Concepts) (MFGE 5200), for instance. This course covers smart factories, sensor networks, and intelligent decision-making systems. In so doing, it teaches students how to model and simulate digital factories and how to integrate these systems into existing operations.

And Organizational Leadership (MFGE 5000) helps students develop communication, emotional intelligence, and ethical decision-making. Educating engineers in communication and decision-making is key to the complex, changing tasks of not only training employees but also integrating advanced technologies and tools in the advanced manufacturing environment. This course prepares students for technical leadership roles, such as those of team leads, project managers, and cross-functional coordinators.

In addition, the content of Statistical Methods (MA 5701) prepares students to lead Six Sigma and continuous improvement initiatives. Other core courses are Tolerance Analysis with Geometric Dimensioning & Tolerancing (MFGE5100) and Industrial Safety (MFGE5500).

Beyond these required courses, others prepare students for some of the specific challenges of advanced manufacturing. For instance, Operations Management (BA 5610), which focuses on lean systems, ERP integration, and demand forecasting, trains students to analyze operations holistically, from inventory to logistics to production. Furthermore, Introduction to Sustainability and Resilience (ENG 5515) recognizes that sustainability is more than just a buzzword. Its content introduces engineers to ecological economics, sustainability metrics, and policy-driven design. Therefore, it builds those systems-thinking skills necessary for leading green transitions, which are crucial for industries like automotive, energy, aerospace, and consumer goods.

Examples of Current Students in MTU’s Online Manufacturing Program

According to John Irwin, Professor and Chair, Manufacturing and Mechanical Engineering Technology, MTU’s online program is ideal for working professionals. Two of Global Campus’s current students are engineers at top-tier automotive companies. In their projects, they are supporting advanced manufacturing by developing methods for increased part production and safety.

For instance, shared spaces where humans and robots work and interact in close proximity are common in advanced manufacturing. One student is working to increase safety for collaborative robotic systems. Another MS Thesis student is collaborating with Pettibone, which produces material handling equipment. They are conducting a lean energy study to pinpoint both direct and indirect energy waste in production. The goal: increasing efficiency without sacrificing productivity.

Since the introduction of graduate degrees in MMET, we’ve had many full-time engineers pursue our programs. And these programs are growing. The Global Campus Fall 2025 enrollment has increased 100% over last spring semester. At MMET, we’re always looking to provide more opportunities for working professionals to pursue their research while earning a respected degree from Michigan Tech.

Learn More About Michigan Tech’s Online Graduate Program in Manufacturing Engineering

All in all, Michigan Technological University has programs that are strategically aligned to support the upskilling needed for manufacturing for Industry 4.0. Graduates of MTU’s online graduate manufacturing program, for instance, are well-positioned for various roles–especially those in leadership–across advanced manufacturing.

Learn more and talk to subject matter experts by attending an upcoming virtual information session on Michigan Tech’s online graduate program in manufacturing engineering.

DETAILS:

- Date: Thursday, June 19

- Time: 11:30 AM (EDT)

- Location: Zoom