The last week of April was World Immunization Week. A campaign of the World Health Organization (WHO), this special event celebrates the development of vaccines to prevent diseases that once ravaged communities. The Copper Country was no exception to the scourge of sickness: measles, meningitis, diphtheria, and other illnesses made the rounds of mine towns, often with devastating effects.

Mining companies took a keen interest in the spread of these diseases and others in their surrounding communities, both for the benefit of the corporation and the good of the workforce. From nearly the beginning of Copper Country mining, company payrolls included doctors, a holdover from the Cornish roots of many early miners. As the region matured, several mines constructed hospitals and medication dispensaries to serve their employees. For a modest monthly contribution and additional fees for inpatient care, workers and their families were entitled to diagnostic services–both at home and at the hospital–and medication. Calumet & Hecla (C&H) offered perhaps the archetypal example of this service. The company opened its first hospital in 1871 and, by 1897, boasted an expanded, state-of-the-art facility with a substantial staff. Patients seeking treatment visited this impressive building on the east side of Calumet Avenue (US-41), just north of Church Street. C&H also operated a clinic in Lake Linden.

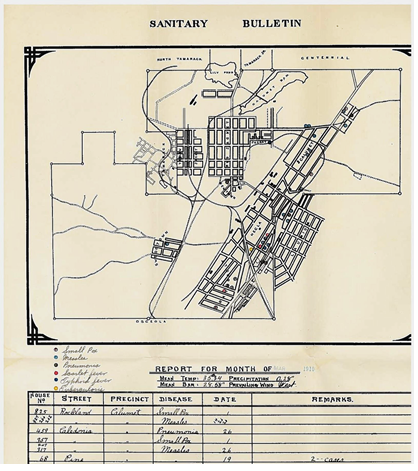

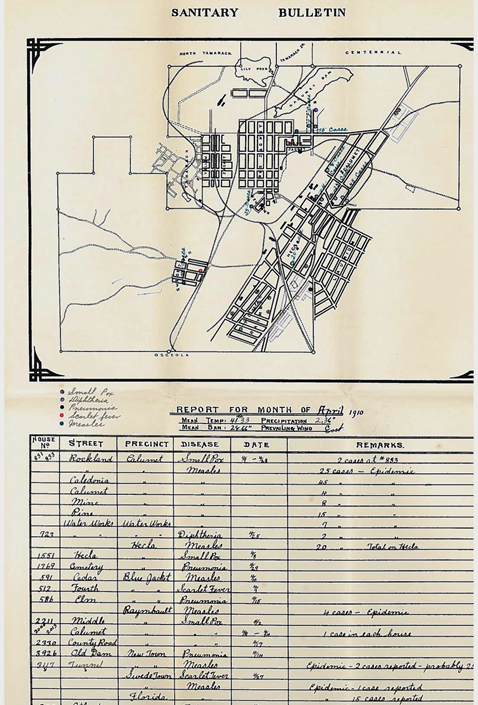

By the late 1890s, C&H hospital physicians also aligned themselves with the growing field of public health. At the end of each month, doctors sent the company’s superintendent reports about the highly communicable diseases–now often preventable with vaccines–that its staff had treated. These dispatches, which C&H titled “Sanitary Bulletins,” recorded the nature of each illness, the neighborhood in which it had occurred, and the address of the patient; in an endeavour that presaged today’s emphasis on data visualization, physicians then carefully plotted the cases on a map of the Calumet area, using colored circles corresponding to the illnesses observed. The month’s average temperature, mean barometric pressure, total precipitation, and prevailing wind direction also featured prominently in these bulletins, which have been preserved as part of MS-002: Calumet and Hecla Mining Companies Collection.

The sanitary bulletins are a fascinating snapshot of the state of public health in Calumet in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Through the meticulous note keeping of the mine physicians, modern researchers glimpse the illnesses that struck the community and the geography of epidemics, how sickness spread through a mine town. In March 1910, for example, a physician was called to Rockland Street in Calumet location–a settlement along the east side of today’s US-41–to tend to a feverish patient, probably a child, who was suffering from a cough, running nose, and watery eyes. An angry red rash had erupted across the patient’s skin. When the doctor came to the home, his diagnosis confirmed what family members had no doubt suspected: a case of the measles. This became the first blue dot–that month’s chosen color for measles–in a wave of illness, the tip of the iceberg.

Four days later, C&H physicians were called to tend to two cases of measles down the road in Hecla location; the following week, the neighborhood where the outbreak had begun saw another four patients with the same disease. Measles began to spread west along Pine Street, branching into the community of Blue Jacket even as it took further hold in Hecla and Calumet locations. In April, the simple outbreak of measles exploded into an epidemic. Pine Street had 18 measles patients, Rockland Street a total of 25. Adjacent Caledonia Street topped them all: 45 residents came down with measles that month. Imagine this happening in your neighborhood! The epidemic, which faded by June, sickened over 200 people. No longer able to squeeze all of the blue dots onto their sanitary bulletin, C&H doctors settled for drawing one dot per street and painstakingly penciling the total number of measles cases beside it.

Although none of the 1910 measles cases appears to have been fatal, the sanitary bulletins often tell of patients who were not so fortunate. Diphtheria, a capricious disease, sometimes dealt a glancing blow–or led to a date inked onto the chart with the word “died” beside it. Pertussis (whooping cough) lingered in homes; a painful annoyance to older children, it frequently led to deadly pneumonia in infants. Meningitis killed without prejudice, taking up to 80 percent of its victims in a matter of days.

Today, vaccines dramatically curtail the spread of these diseases, sparing countless individuals from miserable illnesses and their families from grief at the premature loss of loved ones. Poring over these fascinating artifacts unlocks a vivid story of life and death, a world before widespread vaccination. To discover more of the story, visit or contact the Michigan Tech Archives–our friendly staff are always ready to assist you.

A special thank you to our Assistant Archivist, Emily Riippa, for another well-researched and thoughtful post.