The following post is part one of a two-part series, which was researched and authored by Emily Riippa, Assistant Archivist.

Fall semester is always busy for our department, but October was an especially busy month of outreach for the Michigan Technological University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections. Everyone on our staff had a part to play. It was my honor and privilege to speak at the monthly meeting of the Houghton-Keweenaw County Genealogical Society on some of our most popular documents: the employment records from the Calumet & Hecla Mining Companies Collection (MS-002).

The Michigan Tech Archives holds more than 54,000 of these records for workers–primarily male but, in some instances, female–hired by the company between 1865 and 1957. Astonishing though that number is, it still does not quite capture the vastness of the workforce under the Calumet & Hecla (C&H) umbrella. Records for an unknown number of employees who left the mines before the mid-1890s or stayed on with C&H until its bitter end in 1969 were lost or destroyed before the collection arrived at Michigan Tech. C&H’s habits when it acquired competitors also weighed negatively on documents from those companies: if a worker was employed by Tamarack Mining Company, for example, only before it ceased to be an independent organization in 1917, C&H apparently disposed of his employment information. If he stayed on when Tamarack officially came into the Calumet & Hecla family, the corporation’s clerks transferred his information to a new, C&H-specific document.

Rich with information about such topics as family backgrounds, occupations, rates of pay, and on-the-job injuries, the many cards that have survived are perennially in demand with genealogists, labor historians, and many other researchers. Yet the very wealth of information available often renders the cards challenging to read and decipher. Even more than its biggest competitors–Copper Range and Quincy–C&H created employment cards with a complex structure and devised a collection of information-storing abbreviations as expansive as the workforce it described. For researchers a hundred years later, understanding the C&H language and card structure can be a challenging proposition. In my presentation last October, I provided what I called a Cliffs Notes guide to what a person needs to know to read a C&H employment card, and I am pleased to be able to share a version of that with you. It would be a disservice to the records to abbreviate that discussion too dramatically, so this Cliffs Notes guide will be divided into two posts. The first entry will focus on the information that the cards provide on an employee’s background and personal traits.

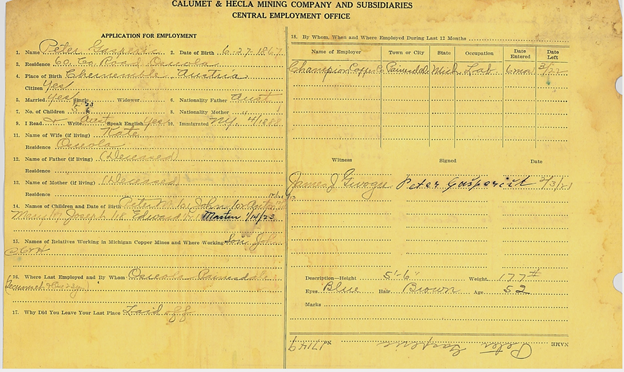

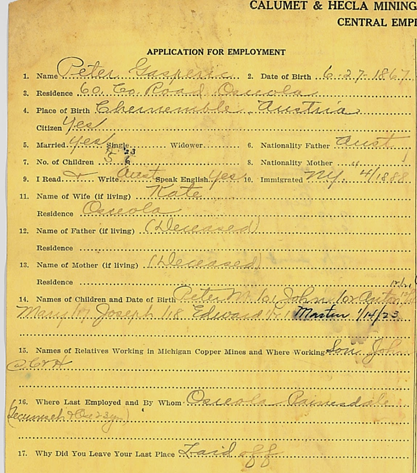

When we speak of C&H employment cards at the Michigan Tech Archives, we are, in fact, referring to two distinct styles of record. A small, dense document that resembles a modern index card came into use for documenting C&H employees in the 1890s. A larger, yellow sheet with a more complex structure replaced it beginning in 1915. While the format might have changed, many of the company’s questions and abbreviations remained constant over the years. Understand the newer C&H employment record, and interpreting its predecessor will be simple. For that reason, both posts will examine the yellow document.

It’s easiest to understand yellow cards by looking at a sample record, so I selected the employment card for a relative of my own, Peter Gasperich. Peter was born in Slovenia and came to the United States in the late 1880s, settling near Calumet. He worked in the copper mines for more than thirty years and concluded his career at C&H, where he was employed at the time of his death.

On the front page of the yellow card, C&H employment clerks recorded the aforementioned information about Peter as an individual. The left side of the page began by asking for a substantial number of details of interest to genealogists; name, date and place of birth, current residence, and status with regard to marriage, citizenship, and parenthood lead the list. A genealogist may find that, if the individual’s name was unusual to American eyes or if the worker was an immigrant looking to blend in with his peers, the name given on the employment card varies from what is given elsewhere. Employees may also have misremembered or been motivated to obscure their years of birth, either to inflate or reduce their ages; this information is worth verifying with other sources whenever possible. It is worth noting, as well, that contemporary names were used for places of birth. Peter was born in Črnomelj, Slovenia, a town then part of the Austrian empire. He provided his hometown using its official German name (Tschernembl), which the C&H clerk attempted to transcribe phonetically–with little success. It took quite a bit of additional research to tie “Chernemble” back to Peter’s actual birthplace.

As they moved down the page, the clerks inquired about the name of Peter’s spouse and where she resided. Employees whose parents were still alive also provided information about them to C&H. Unfortunately, the company was not motivated to collect details about deceased relatives and simply recorded them as no longer living, rendering this section a–no pun intended–genealogical dead end. Names and dates of birth were noted for children, albeit with the same caveats as Peter’s name and age. The questions about Peter’s family also requested details about any relatives of his who were also working in Michigan’s copper mines. If the family member were employed at a different mine, both the person’s name and the name of their employer were listed, along with a succinct abbreviation of their relationship; if the person worked somewhere within the C&H empire, the employer’s name was replaced by the individual’s identification number. This portion of the front page concluded with information about Peter’s most recent employer prior to C&H and his reason for leaving that company.

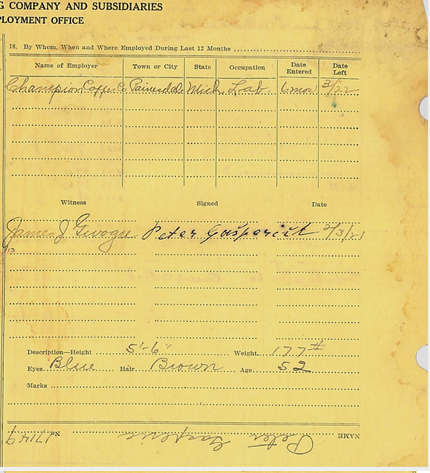

Although the structure of the employment cards varied over the years, the right side of this front page here provided a space for C&H to expand on Peter’s work history. In this more detailed inquiry, the company asked about Peter’s employers in the twelve months prior to his hiring at C&H: the name and location of the firm, the dates that Peter worked there, and the position he held were all noted. At times, an employment card might show a smattering of jobs spread across multiple years: when workers returned to C&H after an absence, the company would simply update existing records rather than creating new ones. The genealogist who sees this apparent disarray on an employment card should see it as a clue that their ancestor moved from job to job with some frequency.

Perhaps more interesting to family history researchers, however, is the description of the employee’s appearance also provided. For genealogists who have only black-and-white photographs of their ancestors–or, in the case of Peter, no pictures at all–these details about hair and eye color, height, and weight are a particular treasure. Rest assured that C&H company physicians, who examined all prospective hires, spared no detail. I know more now about the scars and bodily oddities of long-dead family members than I ever desired to know. On the employment records produced in the years immediately following the 1913-1914 Western Federation of Miners copper strike, a paragraph authorizing a rudimentary background check and vowing no affiliation with the union was also included. By the time Peter’s card was created in 1921, this section had fallen by the wayside; its commitment was now implicit.

The new hire signed the card–or made his X mark–on this page, and a representative of the company added his own signature and the date. Updates here were made in much the same way as the employment history section. At the very bottom of the page, clerks wrote Peter’s name again and added one of the two numbers he was assigned within the C&H system.

The Calumet & Hecla employment cards offer extraordinary insight into the company’s workforce for a bevy of research interests. Hopefully, this primer will prove a useful orientation to the basic history and purpose of the cards, as well as the information available on their front side. A future blog post will turn to the back page, which shifts its attention away from personal details to focus more on a worker’s relationship to C&H. Watch this space for the second part of the guide. In the meantime, if your interest in learning more about your ancestors’ potential ties to C&H has been piqued, if you would like assistance in deciphering a record already located, or if you have any other research questions, please do not hesitate to contact the Michigan Tech Archives. We may be reached via e-mail at copper@mtu.edu or by telephone at (906) 487-2505, and we are always very happy to help.

Very interesting. Thanks for posting! I’ve often wondered if there was company information on the death of my greatgrandfather, Jacob Muretich. He died in the 63rd level of the shaft #9 , South Hecla, Oct. 12, 1910.