The following post is part two of a two-part series, which was researched and authored by Emily Riippa, Assistant Archivist.

Welcome to the second part of a discussion on deciphering Calumet & Hecla Mining Company (C&H) employment records held by the Michigan Technological University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections. This post will concentrate on the back page of a C&H yellow employment card, which emphasized a worker’s job history and relationship to the company. If you missed the initial part of the series or would like to refresh your memory of the card’s front page–where the employee’s personal traits and family connections were in focus–you may find it valuable to reread the prior post before perusing this one.

We’ll continue our exploration of the yellow C&H employment cards, which the company used from about 1915 through at least 1957, by once again examining the sample record of Peter Gasperich, my great-great-grandfather. As a reminder, Peter was a Slovenian immigrant and resident of Osceola who worked for C&H at the time of his death. From the front page of his card, we learned that he was married and the father of seven children, that he had previously been employed by the Osceola and Champion copper companies, and that he was a literate man of modest height and solid build. On the reverse of the card, we will find the bulk of the information related to job titles, the divisions of C&H in which the employee worked, and rates of pay. Parsing this data is often the most complicated part of interpreting an employment card, both due to its density and the number of abbreviated, specialized terms used–enough, it seems, to fill a small book rather than a blog post. Still, with the space we have, let us try to unravel the mystery of the back page, piece by piece.

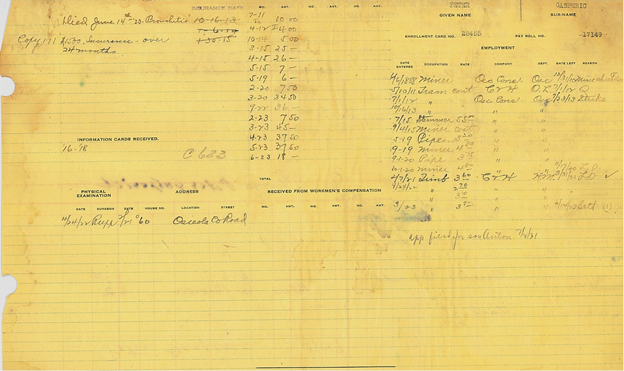

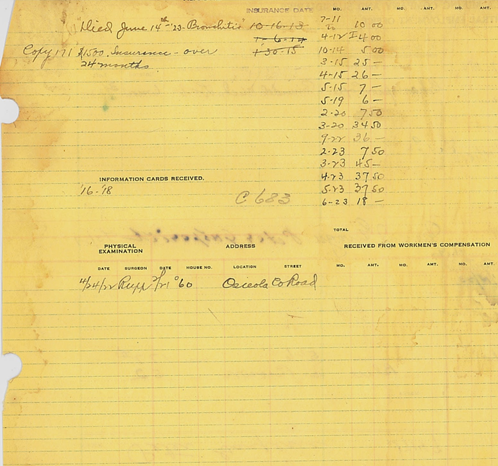

In the upper left corner of this page, C&H set aside a section that can best be described as a General Notes field. Here, the company documented matters like the date and cause of a worker’s death or information about his pension if he received one; here, too, were any explanations for why he left the company–willingly or involuntarily–including times when he and his boss had butted heads. As with the results of the worker’s physical exam on the front page, these remarks were consistently blunt, if not outright brusque: “losing time,” “lazy,” “no good,” to name a few. For Peter, the card’s most prominent note was that he had left the company’s employ permanently with his death on June 14, 1923 from bronchitis. Keep in mind that C&H did not always accurately record causes of death, either deliberately or from lack of knowledge, so it is wise to cross-reference this information with official death certificates whenever possible. In Peter’s case, the state’s explanation–stomach cancer–seems far more likely in light of clues given in other areas of his employment card.

We see those clues as we move clockwise around this part of the card to look at Peter’s financial relationship with Calumet & Hecla. Next to General Notes, the company recorded a list of dates and amounts of cash. These figures indicate money that Peter withdrew from the C&H Aid Fund, a benefit society of sorts operated by the company. A set deduction was taken from each paycheck of employees who agreed to participate, and C&H matched their contributions. Later, if, like Peter, the worker were laid low by illness or injury, he could draw on the aid fund to keep his family housed, clothed, and fed until he could be back on the job. Though generous by contemporary standards, C&H also kept a sharp eye on its aid fund and monitored the frequency and duration of use by each employee. Distrust fell on men who seemed overly dependent on charitable moneys. The company’s observation, however, and its recordkeeping can provide interesting insight to genealogists in particular. From Peter’s employee aid record, I was able to see that he had called upon the aid fund on several occasions, including one string of withdrawals that began in February 1923. It seemed likely that the fatal illness must have begun around this time, and picturing those last few months in the Gasperich house as Peter declined added a new dimension to my understanding of my ancestors.

Below the General Notes and accounts of Peter’s aid fund use came several additional fields whose meaning is more familiar to modern readers: a tally for dates that he had received workmen’s compensation funds for any injuries received on the job, a list of addresses he had occupied and changes he made to his residence, and the dates that he had been examined by a C&H physician. Individuals joining the company had to pass physicals, which were seemingly required at irregular intervals thereafter; any extraordinary results–described in General Notes–could mean the rescindment of an offer of employment, lest the worker become a threat to his colleagues or a financial drain on the company’s hospital.

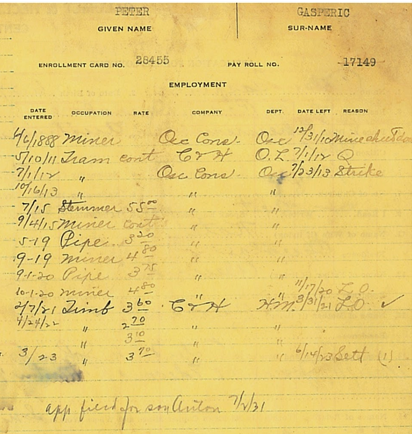

Although interesting, these components are not the meat of the employment card’s back page. That honor belongs to the right side, where Peter’s work history was recorded in meticulous detail. This section began with Peter’s typed name and, below it, two identification numbers: an enrollment card number and a pay roll number (which also appeared on the front page). It is not uncommon for the latter of these numbers to be crossed off if the employee had passed away or replaced with digits in the form P-### if the worker had been pensioned. Further information on any such pensions were recorded, as we have already seen, in the General Notes field. Beneath these numbers came several columns designed to capture the nuances of Peter’s time at C&H. Two of them–the first and the next-to-last–simply listed the dates that Peter began his work, whether at the company or in a new position, and the dates that he ceased to hold that job.

Next was given the title of the occupation itself, often in abbreviated form. To most modern researchers, Peter’s having worked as a “tram” or a “pipe” seems nonsensical, but these terms indicate that Peter worked as a trammer–moving heavy cars of mine rock along a shaft level to be raised to the surface of the shaft–and a pipeman, someone who laid and repaired pipe for compressed air, steam, or water. Similarly, as a timberman (or “timb,” as C&H put it), Peter would have placed and maintained wooden mine structures, like ladders and hanging wall supports. Occupational shorthand abounded through the cards, but two other common terms of note were “dry” for “dry man”–often an older or partially disabled man who kept the workers’ change house clean and supplied–or “sfc,” for surface, preceding a job to distinguish employees who did the work on one side of the ground or the other. Keep in mind, as well, that sometimes words that seem straightforward today had nuances at the time the cards were created. It’s easy to think that every underground man at C&H was a miner, but the term was specific in its meaning and referred only to workers who drilled and blasted rock in search for copper.

Under the Rate column, C&H provided the wage paid for each occupation that an employee held. Notice on Peter’s card the word “cont” in several places, indicating that he was paid wages specified in a contract he had negotiated with the company. For other jobs, the amount of pay was given in numeric form: a monthly wage, generally speaking, until about 1918, when a daily rate began to be used. In the 1940s, C&H switched again, transitioning to listing pay in hourly terms. If you see an ancestor’s income listed as cents and fractional cents, that is a good indicator that this pay was hourly. If the card bears a number like $55.00, the rate was monthly.

The Company and Department (Dept) headings can also be a source of confusion. Although it is useful shorthand to think of C&H as a single entity, in many respects it was more of a corporate umbrella containing component companies, including some former competitors. A little history may help to explain this. Calumet & Hecla began life as two related organizations–the Calumet Mining Company and the Hecla Mining Company–that were combined into C&H in 1871. To ensure the company’s continued success, in the early 1900s C&H began to acquire large amounts of stock in some of its local competitors, placing them under C&H’s control. This method brought Osceola into the C&H “family” in 1909 and Tamarack in 1917. Ahmeek, Allouez, and Centennial were purchased outright in 1923, leading to the creation of the Calumet & Hecla Consolidated Copper Company. Other mines and facilities also came under the umbrella over the years, creating a C&H that employed workers in places far beyond the little village once called Red Jacket.

Given this history, the Company and Department columns seem more logical. “Company” allowed C&H’s clerks to specify which part of the organization an employee belonged to: Osceola, Kearsarge, South Hecla, C&H proper, etc. “Department” permitted greater specificity: a Hecla miner could be said to work in the #9 shaft, for example, or a C&H general laborer could be designated as a smelter employee. For companies that already had subsidiaries at the time of their incorporation into C&H–like Osceola’s operations at Kearsarge–the Department field could also be used to further distinguish among the company hierarchy. At other times, however, the two sections simply repeated each other. On Peter’s card, for example, we can see Company listed as in one place as “Osc. Cons,” referring to Osceola Consolidated Mining Company, and the Department simply listed as “Osc,” not shedding much light on his particular place within the organization. Where greater details than these were provided, these fields in conjunction with the Occupation column offer the genealogist significant insight into the nature of an ancestor’s work.

As with Occupation, abbreviations for Company and Department abound. Decoding the meaning of the more obscure shorthand is an ongoing project at the Michigan Tech Archives. A few basic words of advice are worth sharing at this point, however. Common entries in the Company column–in addition to the ones mentioned above–include LMS & R[ef] Co for Lake Milling, Smelting, and Refining Company; Tam for Tamarack, west of Calumet; I.R.C. and I. Royale for Isle Royale Copper Company, near Houghton; and a dizzying array of options for the Tamarack, Osceola, and Ahmeek mills on Torch Lake. Department abbreviations featured likewise ran the gamut. Rkhs, rchs, and r. hse indicated an employee assigned to the rock house; sm, smelt, and smelts, the smelter; mill or st. m, the stamp mill; or sfc, the surface. Where a number or single letter were given in the Department column, it referred to a particular designated mine shaft at the company in question.

Moving past the Date Left column that was mentioned earlier, we look at last to the Reason column, which provided a rationale for Peter’s departure from each position. Peter’s card included three of the most common explanations: Q for quit (he chose to find work elsewhere), L.O. for laid off (economic factors led C&H to cut his job), and Sett for settled up (he died, and C&H concluded its business with him). This last term also was used to address workers who resigned, possibly in lieu of termination, and sometimes men who had been drafted into the armed forces. If an employee’s reason for departure was given as “Dis.,” he certainly was dismissed or discharged–fired. “Ret” workers had simply retired. Peter’s card also used the word “Strike” in the explanation column. This does not necessarily mean that he was an active part of the 1913-1914 Western Federation of Miners (WFM) copper strike; rather, C&H used it to indicate that the mine at which he had worked shut down during that time. Occasionally, recordkeepers placed numbers in parentheses next to one of these reasons, indicating a more detailed explanation was available next to the corresponding number in the General Notes section. Look to that section, as well, to distinguish men who had joined the union from men whose note of “Strike” simply meant that they were bystanders: if the note indicates that a man burned or gave up his WFM book, he was a union member.

What more can be said about the Calumet & Hecla employment cards? Quite a lot. These documents mirror the organization that created them: they are as broad as the workforce and as deep as the company’s copper mines. The Michigan Tech Archives earnestly hopes that this overview of the C&H records has been useful, limited by necessity as it may have been. If your interest in learning more about your ancestors’ potential ties to C&H has been piqued, if you would like assistance in deciphering a record already located, or if you have any other research questions, please do not hesitate to contact the Michigan Tech Archives. We may be reached via e-mail at copper@mtu.edu or by telephone at (906) 487-2505, and, as always, we are very happy to help.