A 1960s-era roadside mom-and-pop-style motel, which may or may not still be taking reservations.

Cords of firewood orderly stacked in advance of a long winter and lake-effect snows.

An 1800s lakefront street now inland, separated from Lake Superior by dredge spoils, sawdust, or other (non)toxic materials, afterthoughts dumped in a different era.

1920-era bungalows transitioning to newer housing styles, larger yards, and garages facing the highway heading away from downtown.

Small aspens shooting upward, their roots expanding cracked pavement within a formerly-used logging road.

These descriptions are of a few common landscapes on the amalgam of American and Canadian highways now known as the Lake Superior Circle Tour route. Today, we take for granted the ability to drive around Lake Superior’s shoreland communities on a connected system of paved roads, designed to the exacting specifications of modern engineering. Glossy tourism brochures and travel guides showcase selected scenes to cultivate romanticized impressions of the lakeshore and nearby communities. Travel writers in Midwest Living, Lake Superior Magazine, and other publications hype up the Lakeshore’s natural and built environments alike.

Landscapes are inherently suited for visual methodologies. Rephotography helps scholars to trace the evolution of landscape tastes, and a small yet growing group of geographers, historians, and artists have conducted rephotography as part of constructing case study narratives that inform theory about social, environmental, geological, technological, or legal changes. In this vein, I am conducting rephotography of roads around the Lake’s edges to investigate the roles of culture, technology, and policy in guiding landscape change. Photographs can help illuminate landscape change provided that other spatial and historical data are available to researchers to piece together portions of the past, or the landscape’s “backstory.”

My visits to the Michigan Tech Archives and other museums and archives have been to find photographs and textual documents to construct landscape backstories of coastal communities and connect them with theory. Planning and zoning documents, park management plans, media reports, and correspondences between grassroots activists and decision-makers are some examples of the kinds of documents necessary to explain how Lake Superior’s coastal landscapes look the way they do today.

I am selecting photographs from the Copper Country Archives Photo Files, rephotographing them, and connecting their changes to theories of wayfinding and land use classifications. The late David Lynch popularized categories of paths, edges, corridors, nodes, and districts in his classic The Image of the City (MIT Press, 1960, still in print). Other images I am considering highlight change in notable land-use classifications such as public space, civic space, residential, commercial, and industrial land uses.

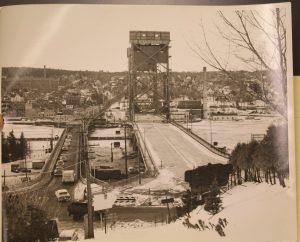

As the only bridge connecting the Copper Country across Portage Lake, the present-day Portage Lake Lift Bridge serves as a prominent node. Residents’ and tourists’ cognitive images of the Copper Country most likely include this landmark. Accordingly, the Bridge serves as a key node for photographs, parades, and political rallies. Given the traffic and raising/lowering of the bridge deck to allow ships through, this iconic landscape element is arguably the closest the Copper Country gets to traffic jams today. Owing to the traffic, a variety of alternate methods have been used in the past, such as ice roads, and correspondences housed at the Archives’ Vertical Files mention ideas floated for the future, such as ideas for a second bridge to alleviate traffic as well as bypass Houghton to the East.

Likewise, the Archives’ Copper Country Vertical Files have been a good starting point for finding content on landscape-oriented issues. These include information with broader impacts outside the Copper Country, such as correspondence documenting disagreement between the Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) and communities hoping to lower speed limits on stretches of state and federal highways.

In 1944, the State of Michigan created Porcupine Mountains State Park as a solution to concerns of proposed clear-cutting. Over a decade earlier, State of Michigan Highway Commissioner Murray Van Wagner worked to create a road west from Silver City to Lake of the Clouds. This 1936 article, “Porcupines Road Nearly Complete” provided an update on the gravel road, flanked by a 400-foot right of way buffer zone obtained to for the purposes of guiding the appearance of landscape aesthetics. Two decades later, Michigan Governor George Romney (Mitt Romney’s father) sought to prevent the extension of lakeshore road west from Lake of the Clouds to Gogebic County. The Lake Superior Circle Tour Route today would presumably have a different route if paved roads exist along that stretch of lakefront, in place of the present expanse of a contiguous wilderness area for outdoors enthusiasts, flora, and fauna alike. Although newspaper articles cannot tell the full backstory of landscape changes themselves, they are helpful for me to provide context, to serve as leads on the potential availability of laws and management plans, and to compare with other evidentiary sources.

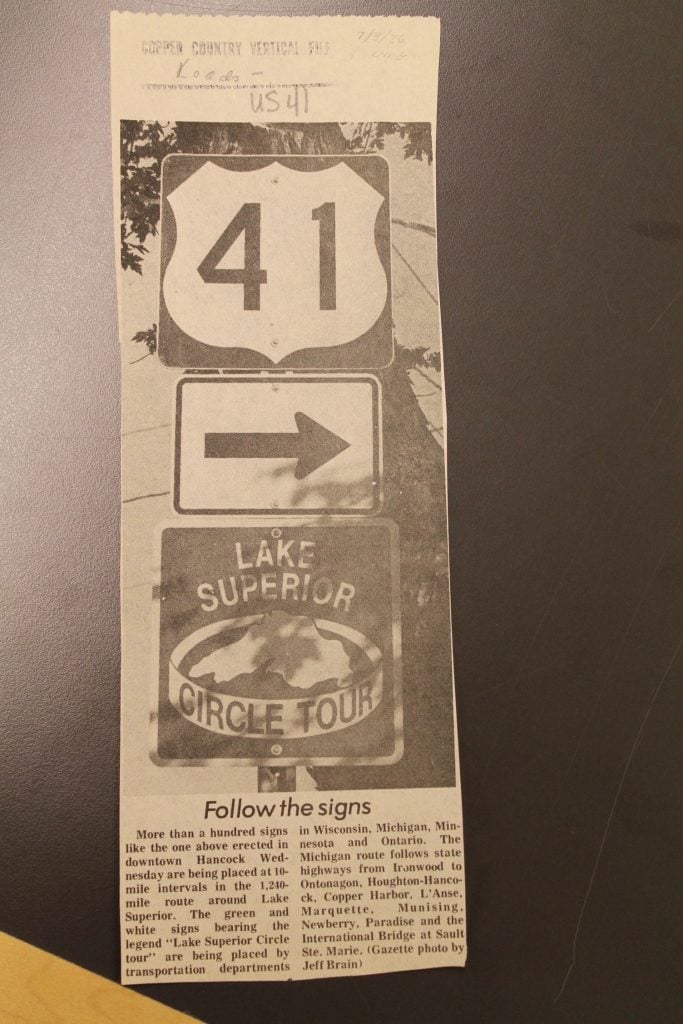

The now-ubiquitous “Lake Superior Circle Tour” green and white signage program is only a generation old. On the eastern shores of Lake Superior, sparse population, limited commerce, and rugged topography diminished funding priorities for blasting a highway route through granitic bedrock. Not until September 17, 1960 could the touring public feasibly circumnavigate the lakeshore on wheels. That day, Ontario Prime Minister Peter Frost and a motorcade of other dignitaries cut a ribbon to commence the official opening of a Lake Superior Circle Route. Afterward, North American media hailed the completed road through a variety of monikers, such as the “Lake Superior International Highway” and “Lake Superior Circle Route.” (The present-day label of “Lake Superior Circle Tour” derives from then-Michigan First Lady Paula Blanchard’s 1985 efforts to promote tourism.) The Circle Tour sign shown here is an example of a “reassurance marker” to symbolize the route for travelers. The Daily Mining Gazette article of July 3, 1986 mentions that signs were being installed that week at 10-mile intervals.

Although the Archives serves as a regional repository for the Western Upper Peninsula, its holdings contain useful documents of interest to scholars working on other areas of Lake Superior as well. The Keweenaw Historical Society Collection appears as if it would exclusively focus on the Keweenaw Peninsula, but holds a wealth of documents from seemingly disparate lakeshore locales. One example is the collections on Silver Islet. Due north of Isle Royale, Silver Islet is the site of a short-lived silver mine, once led by William Frue of Houghton. Shareholders’ Meeting Reports and other records help piece together the story of strategies to modify the landscape at Silver Islet, with regard to both lakeshore development at the Silver Islet community on the mainland, and expansion of the island’s size using leftover rock from the silver mine. Other far-flung files in the collection include photographs of Marquette, updates of roadbuilding through Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, and documents about the Soo Locks.

This Spring, I will rephotograph key places and landscape elements in order to examine landscape change along Lake Superior’s shores and settlements. Incorporating these photos with geographical and historical data into a book will interest both scholars of cultural landscapes and segments of the general population interested in seeing how Lake Superior’s landscapes have evolved. I will share some of these images at a Michigan Tech Copper Country Archives Speaker Series talk in June.

Editor’s Note: Matthew Liesch is Associate Professor of Geography and Environmental Studies at Central Michigan University. His publications range from iron and copper mining heritage to use of GIS in archaeology to conservation easement modeling. Other current research includes a Mott Foundation-funded project integrating interview data into economic modeling to examine return on investment of the federal Great Lakes Restoration Initiative program. Liesch is a former Chair of Main Street Calumet’s Economic Restructuring Committee and is a Planning Commissioner for the City of Mount Pleasant.

really interesting photos.