Arguably, no event changed the Copper Country more than the 1913-1914 Western Federation of Miners strike, and no tragedy has left a deeper mark on the community than the Italian Hall disaster.

Those who grew up in Houghton County or who have studied its history know immediately what these words connote. For others, some background needs to be provided. In July 1913, members of Western Federation of Miners (WFM) locals in Michigan–dismayed by rates of pay, safety conditions, work schedules, and the introduction of new technologies that would allow the mines to reduce their workforces–elected to strike. The mining companies, including the mighty Calumet & Hecla, responded by shutting down operations; they had enough cash to outlast the union, whose coffers had run dangerously low following strikes elsewhere, and they felt secure in their position compared to the untested, newborn local unions.

The tension everywhere in the Copper Country felt like electricity–powerful, untamable, unpredictable. Like electricity, it arced wildly at times, catching both ardent activists and innocent bystanders in its path. Strikers beat and hurled projectiles at those who had decided not to join the union. On several occasions, shots fired into private residences killed workers. After two striking miners and representatives of the Copper Range Company sparred over trespassing accusations in August, a group of hired deputies and non-striking workers descended on the roaming men’s boarding house to confront them. Tempers boiled over into gunfire, killing two men inside the structure who had had nothing to do with the dispute. In December, members of the WFM decided to send a message to “scabs” by firing a Painesdale immigrant boarding house run by the Dally family. Thomas Dally, along with non-striking boarders Arthur and Harry Jane, lost their lives. Other moments of violence punctuated the strike: a thirteen-year-old girl shot in the head near Kearsarge, a man found dead on the sidewalk in Houghton, dozens of other incidents of anger and intimidation from both sides. Many employees returned to work at the mines as they reopened, needing to put food on the table and finding the union falling short of its promises. The benefits the WFM promised to those who stayed on the picket lines couldn’t make ends meet. As Christmas approached, the strikers–and their families–needed encouragement.

The Ladies Auxiliary of the WFM organized a party to be held on Christmas Eve at the Italian Hall in Calumet. The hall itself was an elegant choice. On Seventh Street, just steps from one of Calumet’s biggest thoroughfares, the gathering place of the Societa Mutua Beneficenza Italiana sat perched above a tea shop and saloon. The building, which opened in 1908, replaced earlier incarnations that had been destroyed by a windstorm and a fire. As the families attending the party climbed the steps, they were greeted by “Georgia pine, maple flooring, and a highly ornamental steel ceiling” some eighteen feet high, as well as “a balcony… well trimmed with a neat balustrade and ornamental columns.” A stage, dressing rooms, and spaces for “lodge purposes” rounded out the amenities. The children were excited for Christmas and for presents. The parents were tired of worrying about money, about jobs, about their future in the Copper Country. A night of entertainment and relaxation in these fine surroundings wouldn’t erase their troubles, but it would take their minds off what needed to be faced after Christmas.

It all ended in tragedy. Midway through the party, someone–whose identity and motivation have never been confirmed–called out that there was a fire. Word radiated through the hall instantly. Some guests hurried down the fire escape at the rear of the building. Most attempted to evacuate through the main stairwell, the one that they had climbed from Seventh Street just a little while earlier. As the partygoers crowded onto the steps, desperately trying to flee the supposed blaze, they fell over and against each other. No one could reach the doors; the growing yet immobile mass of people before them kept the exit from reach. Slowly, more than seventy children and adults suffocated under the crush of humanity in the stairwell.

There was no fire.

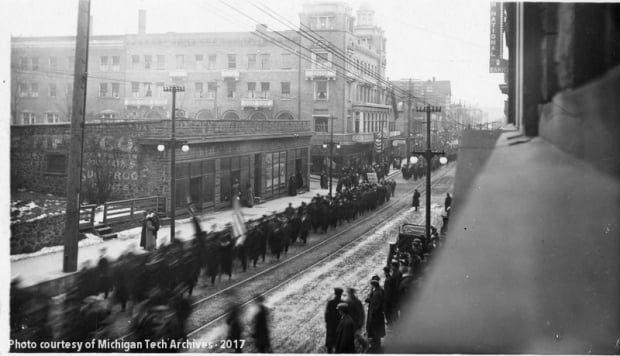

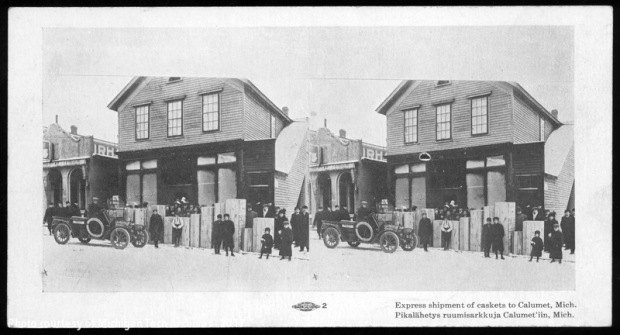

After the disaster, Calumet grieved in a way it never had before and has not since. Undertakers ordered express shipments of caskets from beyond the Copper Country: the stock they had on hand could not meet the need for so many dozen coffins, both sturdy for adults and pitifully tiny for children. Funeral processions marched along the broad lanes of Calumet to Lakeview Cemetery, where survivors laid their loved ones to rest in mass graves and private plots. Witnesses said that the burial ground had never seen so many mourners. Families stood at the edge of the opened ground and knew that what had happened at the Italian Hall had forever changed them. It left vacant chairs around the dinner table, closets of clothes that would never again been worn, toys that would sit idle ever after. For decades after, many in the Keweenaw struggled to speak of the Italian Hall, other than to warn their children never to shout fire in a crowded place.

Conversations about the event, however, frequently introduced a detail that became a pervasive urban legend. Why had those fleeing the hall been unable to open the doors? “Well,” said some, “because those doors opened inward.” The theory would certainly account for much of the difficulty: if the doors needed to move into the hallway to let anyone out, the sheer number of people before them would have prevented anyone from escaping. A photograph of the entrance to the stairs that circulated afterward compounded the confusion: it showed two sets of doors, one of which appeared to open onto Seventh Street and one of which seemed, from the photographer’s vantage point, to open back into the stairwell. The myth of the inward-opening doors became firmly entrenched. After the demolition of the Italian Hall in 1984, a historic sign went up on the spot, proclaiming that this faulty design had played a role in the deaths. That sign has since been replaced. Articles in the Daily Mining Gazette in the 1980s, brief books penned by local authors, the federal Historic American Buildings Survey, and blogs about topics as diverse as Bob Dylan and Michigan history further perpetuated the tale. One can find institutions as august as Michigan State University and the Library of Congress standing by their assertion to this day.

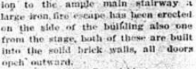

Documents from the time, however, point to one conclusion: the doors of the Italian Hall opened outward. The Calumet News reported in its article on the new hall–written in October 1908, long before the strike was on the horizon–that the architects and builders had been particularly emphatic about ensuring the safety of the doors. In the wake of two deadly fires (the Iroquois Theatre fire in Chicago in 1903 and the Collinwood School fire in March 1908) where problems with doors had been a contributing factor in nearly 800 deaths, public spaces and their exits came under particular scrutiny. The ubiquity of panic bars and doors that open in the direction of egress have their roots in these disasters. Seeking to reassure the people of the Copper Country, the Calumet News took great care to say that the new Italian Hall, its auditorium, and its businesses had been made safe. The reporter wrote, verbatim: “All doors open outward.”

The confusion over the photograph is easy to understand and somewhat more challenging to resolve. Architectural and archival investigation by Keweenaw National Historical Park staff, in conjunction with other historians, a few years ago concluded that the second set of doors–the ones that seemed to open inward–were almost certainly hinged double doors. These would have folded up rather than swung open, but they folded toward the street rather than toward the stairs. A blog post on the website of Gary Kaunonen and Aaron Goings explains this investigation in further detail and with thoughtful diagrams.

What happened at the Italian Hall, the senseless loss of so many innocent lives, and the influence it had on the community should never be forgotten. On a beautiful summer day in 2019, we remember a cold winter night in 1913. We always will.

It is good to see that this horrific incident has not been forgotten. I am glad the myth has been debunked. Growing up in the Copper Country I too believed this myth as told to me by my father.

Great work on setting the record straight. I look forward to more from the wonderful folks at M T U archives.