The Michigan Tech Archives has been blessed with photographic good fortune. Ever since Joseph Nicéphore Niépce set a rudimentary camera up to his window at Le Gras, France, in the late 1820s and captured his first successful still image, people have been drawn to photographing their families, their homes, their neighbors, their pets, events of their communities–anything that catches the eye and seems to cry out for seeming immortality on film. As the Copper Country industrialized and grew in the late 1800s, and as cameras became available to more than just scientists and inventors, the Keweenaw Peninsula came into focus through the lens. Many of the images that resulted, whether taken by trained photographers or hobbyists, have made their way into our archives. They capture scenes of simple family life, booming industry, and bustling towns that have faded away.

Among the prolific photographers of the Copper Country–including peers like J.W. Nara and J.T. Reeder–Adolph (or Adolf) F. Isler made his mark in a particularly profound way. At the time of his death, the Daily Mining Gazette wrote that he “probably had a wider acquaintance among the pioneers of the whole Lake Superior region than any other man in northern Michigan.” A true Renaissance man, Isler devoted himself intensely to a wide range of interests, each of which came to mark and shape his character and career.

Isler was born on December 20, 1848, according to his death certificate. Most sources indicate that he was a native of Switzerland; the Isler family moved from Adolph’s birthplace in the mid-1850s and came to North America. Around 1860, the family settled in Hancock, where Adolph’s father, Henry, set up practice as a physician. There, Adolph grew up alongside the burgeoning mining community. No wonder “the building up of the great mining industry of the Lake Superior copper region,” as his obituary described it, fascinated him for the rest of his life.

The Islers led a traveling life. In his youth, Adolph apparently carried the mail extensively throughout the Copper Country, bearing sacks by foot, by dog sled, and by horse cart from Hancock north to Eagle Harbor. By 1870, he and his father had relocated to Marquette, where the younger Isler labored as a store clerk. Subsequently, he established his own apothecary at L’Anse. Someone who has fallen in love with the heart of the Copper Country cannot stay away for long, however, and the Islers moved back to Red Jacket. Romance blossomed there between Adolph and a young English widow, Anna Rowe Retallack; the two married on March 7, 1878. Isler’s fatherly love–a trait reflected in his frequent choice of children as photographic subjects–knew no end, and Anna’s little girl Winifred (“Winnie”) from her first union became his daughter, too. Ten months after the wedding, Lena Isler was born. The happy young family settled down on First Street in Red Jacket, where the census taker found them in 1880.

Although Isler seemed poised to embark on a medical career, following in the footsteps of his father, his vast range of interests soon led him elsewhere. By day, he worked as a pharmacist at Calumet & Hecla; outside of work, he increasingly focused on photography and journalism. In part, his decision seems to have been driven by a natural inclination to the news: he sought and received roles as correspondent for a number of publications, including the Mining Journal out of Marquette. Collections of Isler’s photographers now in the Michigan Tech Archives also show a dramatic uptick in production in the late 1880s into the 1890s, coinciding with Isler’s decision to invest himself more completely in the art. One cannot help but wonder, too, if there was a sentimental side to his increased interest. The years between 1880 and 1900 proved to be times of great personal loss for Adolph and Anna Isler, despite the birth of son Harry Fred in 1886. In 1883, little Winnie, described as “bright beyond her years” and endowed with “gentle manners [that] endeared herself to teachers and playmates,” died following a brief illness in 1883. She was a little shy of ten years old. By 1900, the Islers had welcomed–and buried–four more children. In 1888, Dr. Henry Isler passed away at the home of his son and daughter-in-law. Adolph’s brother, Arnold, died young, and the Islers took in his daughter, Marialotte. Perhaps, with such painful evidence of how tenuous one’s hold on life could be, Isler felt drawn to do something that would offer an enduring reminder of people and places slipping away.

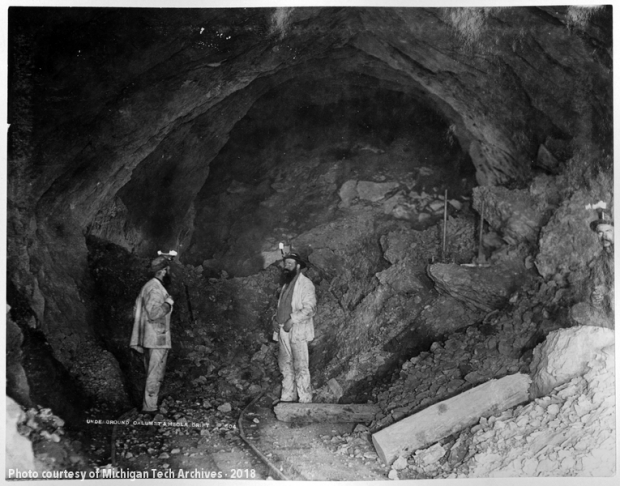

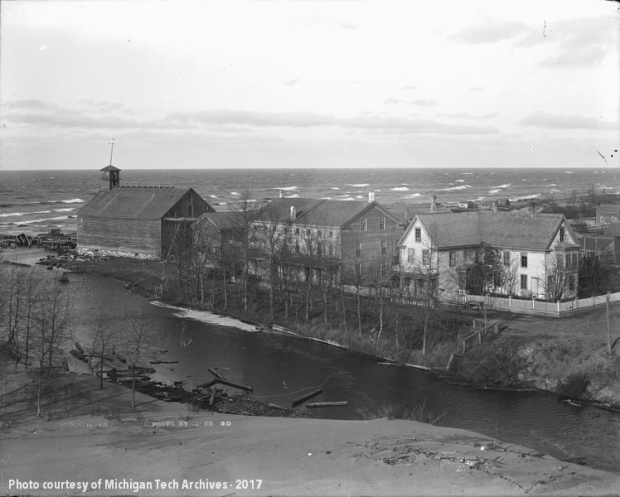

Isler’s photographic style soon developed a distinct flair. Children scampering down the sidewalk or playing in the family home often came into focus. In streetscapes captured during the height of a Copper Country winter, Isler propped a pair of snowshoes somewhere in the scene. Whenever he could, he scaled a tower, a smokestack, a building to take in the most expansive view possible of the town or mine unfolding beneath him. Keweenaw characters who enjoy panoramic photos owe much to Isler’s intrepid character–and fearlessness where heights were concerned.

Although Isler had left his job at C&H in favor of the Calumet News, the Hancock Evening Journal, and amassing one of the most impressive mineral collections to be found in the region, the company nevertheless relied on his expertise when it decided to assemble a certain exhibit of its own. As C&H opened its own library, it called upon Isler to select “a very complete collection of photographs of the region” that should become part of the new holdings. The vivacious Isler complied with great enthusiasm and even continued to add to the project until shortly before his death.

In about 1911, Isler’s health took a downturn. Physicians diagnosed bladder cancer. In January 1912, on the recommendation of his doctors, Adolph and Anna went south to Ann Arbor, there to seek treatment from the medical staff associated with the University of Michigan. The operation itself was a success, removing the malignancy, but Isler’s weakened body could not endure the infection that followed. He contracted pneumonia and rapidly took a turn for the worse. Early in the morning of January 23, Adolph Isler died in the hospital. “Mr. Isler’s figure, with its flowing, iron gray whiskers, his camera or fold of magazines and papers, and his little brown dog” would tramp the streets of Calumet, climb a smokestack at the mill in Lake Linden, or wander the shores near Eagle River no more.

Surviving Isler were his wife Anna, his daughter Lena, and his son Harry. His body was laid to rest in Calumet’s Lakeview Cemetery. His photographs found new homes around the Copper Country before many arrived in the Michigan Tech Archives, where generations continue to discover scenes of Keweenaw past.

Interesting bunch of pictures that us neophyte history nuts never knew existed. I really enjoyed them …I bet there are a lot more at the archives. Maybe we should head over there and see………………………