Author’s note: In 2018, we published a piece on three remarkable women from the Brockway family. The tale concluded with an allusion to Anna, the youngest Brockway daughter, and the promise that her story would be told on another day. That day is today.

Anna Brockway Gray believed in living boldly and without a moment wasted.

This, at least, is the impression created by the documentation left of her life. She did, she thought, she moved with great enthusiasm. She made choices and mistakes with decisiveness. She forged a path of her own in education, in medicine, and in publishing.

Of course, for those acquainted with Copper Country women, Anna’s determination was hardly surprising.

We have no official record of what February 1, 1851 was like at the tip of the Keweenaw. Likely, the day dawned like most Upper Peninsula mornings: cold, with a thick blanket of snow and the great hush of winter surrounding the Brockway residence. Nestled in the snug warmth of their home, thirty-four-year-old Lucena Brockway brought her fifth child into the world. She and husband Daniel christened their newest daughter Anna Medora, a name shared by a picturesque lake not far from their home. By name and by inclination, the newest Brockway would enjoy a deep and lifelong connection to Michigan.

Although the Brockways were pillars of Michigan’s northernmost communities, they also wandered. In those days, the Copper Country had just begun to boom; mines broke ground, flourished, faltered, failed. The family went where opportunity beckoned. Anna claimed the Northwestern Mine, where her father acted as agent, as her birthplace; she spent portions of her early years in Copper Harbor, in Eagle River, at the Cliff Mine, and downstate in Kalamazoo County, where the census taker found her and her parents in 1870. Anna became intimately acquainted with the roadways and waterways of the state, and perhaps the constant relocation helped to inspire a fascination with her homeland. As a young woman, she moved yet again to enroll in Albion College, where her uncle William Hadley Brockway served as an administrator.

Opportunities for women’s education beyond the offerings of local public schools increased in the mid-19th century, but Albion was still something of an outlier. Both sexes could partake in the degree-granting collegiate program as of 1861, an option available at few other institutions in the United States; the school also offered a preparatory curriculum for those seeking to ready themselves for further studies. A catalog from the 1859-1860 academic year asserted Albion’s convictions about women in the classroom: “the question of the ability of the female mind to contend successfully with that of the more favored sex has been too long settled to require discussion.” To the students of advanced classes, Albion promised “a thorough and systematic course of study; equal at least to the scientific course pursued in many of our Colleges.” Anna more likely than not attended preparatory lectures, based on a list of degree recipients published in 1910. If, by the time she arrived in the late 1860s or early 1870s, the curriculum remained comparable to that offered in 1859, her studies might have included trigonometry, algebra, chemistry, anatomy and physiology, logic, grammar, rhetoric, and history. The time at Albion helped to form an Anna Brockway who was ready to take on her greatest challenge yet.

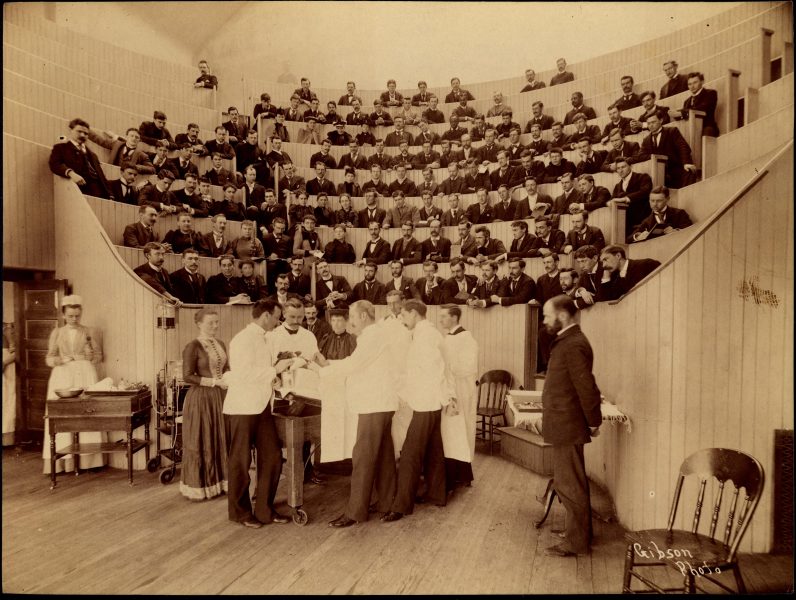

The first woman received a degree from the University of Michigan Medical School in 1871. Dr. Amanda Sanford collected her diploma while male classmates showered her with spitballs to show their disapproval. Seventeen other women joined the medical course in the first year it had been opened to pupils of their sex. Emma Call, one of the inaugural female students, recalled that her peers were “naturally the objects of much attention critical or otherwise (especially critical) so that in many ways it was quite an ordeal” to study there. Most instructors treated the women fairly and with reserve, despite insisting that their lectures be conducted separately from those offered to male students. In chemistry class, however, instruction was coeducational, and certain men shouted and stomped their feet when women walked into the room. The “antiquated professor” who taught the course told “coarse, ribald stories” to his pupils, as Adella Brindle Woods recalled from her 1873-1874 studies. He “looked upon us women students as monstrosities.” Another instructor “was just and often said we were good students, always adding he doubted if we would ever become successful practitioners.”

The women showed how wrong his doubts were.

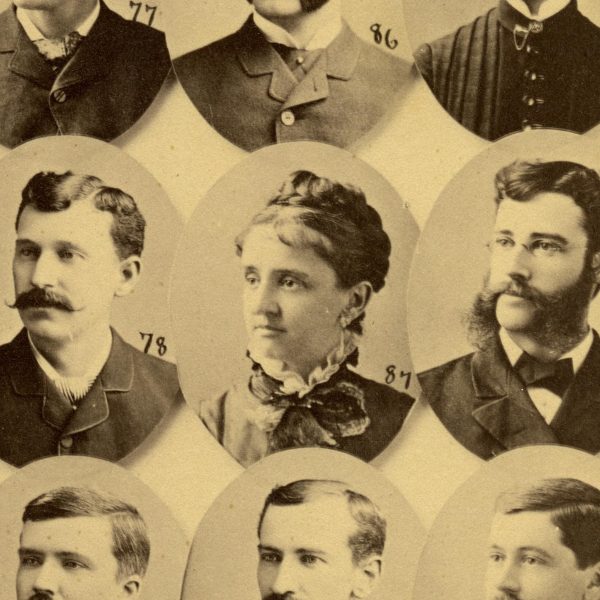

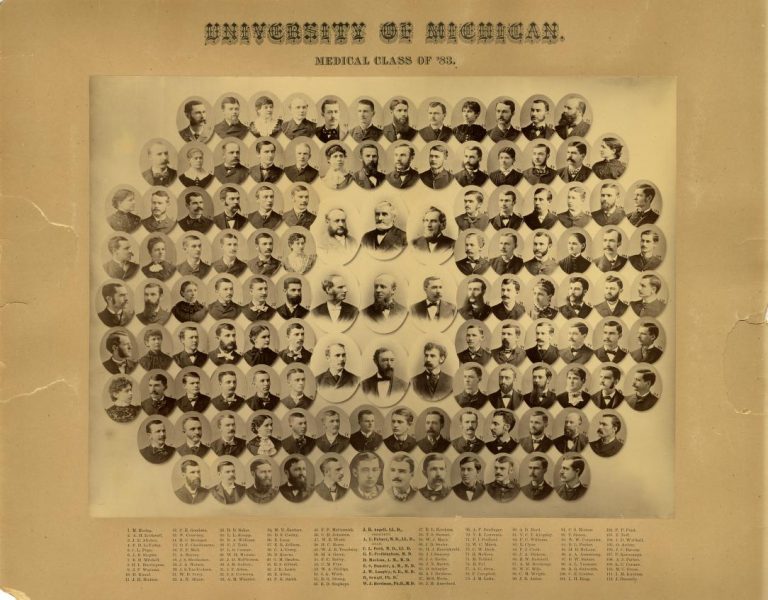

Anna Brockway arrived at the University of Michigan in about 1880 to follow the trail that Amanda Sanford and her peers had blazed. The medical school itself was in flux at that time. When Michigan had first begun to educate doctors, the course of study consisted of a cycle of six to nine months of scientific and practical lectures that each pupil experienced twice. In 1877, the medical school expanded its curriculum to include a three-year option, which became mandatory in 1880. Clinical rotations in hospitals and laboratory work enjoyed new prominence in these studies. Anna’s training as a physician likely mirrored the late 1880s curriculum presented by Michigan historian Horace Davenport in his educational history of the medical school. In the company of a handful of other women, she spent the next three years doing dissections, conducting urinalysis, studying tissues under microscopes, and attending courses on physiology, obstetrics, pediatrics, medical jurisprudence, surgery, and physical diagnostic techniques, among others. The years of hard work and diligent study honed her mind and sharpened her practice, and Dr. Anna Medora Brockway joined the ranks of physicians upon her graduation in 1883.

The new Dr. Brockway’s heart remained in Michigan, but her medical career took her to a different Lake Superior town. She hung out her shingle in Duluth, Minnesota, shortly after leaving Ann Arbor. Her pioneering place in Duluth soon attracted the attention of some of America’s most famous suffragists: Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Matilda Joslyn Gage noted her medical practice as groundbreaking in their 1886 publication History of Woman Suffrage, Volume III.

As her fledgling practice began to take flight, so did another new avenue in her life. She became acquainted with a local attorney, Willard Gray, and the two married in Superior, Wisconsin, on April 15, 1884. Five years later, they relocated to the Keweenaw to advance their professions closer to Anna’s home and her aging parents. A son, whom Anna and Willard named Perry Brockway Gray, was born in Lake Linden on November 17, 1889.

While Perry flourished, the Grays’ marriage rapidly disintegrated. Anna filed for divorce, citing cruelty on Willard’s part, in January 1900. Her parents had passed away the year before, and she and her son ventured south to Grand Rapids. By 1910, they had relocated again to Detroit, where the University of Michigan mailed Anna a copy of the University Bulletin bearing the name “Mrs. Willard Gray.” A letter back to the college, now maintained with Anna’s necrology file at the Bentley Historical Library, captured the doctor’s spirit and autonomy in her own words:

“I have just received the University Bulletin addressed to Mrs. Willard Gray. I wish to ask that the address be… as I wrote it, Mrs. Anna Brockway Gray. Another woman writes herself Mrs. Willard E. Gray. Moreover not even Mr. Gray ever wrote me in that way nor has any one ever done so. My friends would hardly know that I was meant.”

Perceiving in her own misaddressed letter a broader problem, and bespeaking her deeper opinions on how women ought to be known in the world, she continued:

“Moreover I would suggest that each lady alumnus be recorded by the name under which she graduated plus her married name. Mrs. Willard E. Gray would mean nothing to those who [were] with me at the University, but Mrs. Anna Brockway Gray would identify me at once.

Kindly make the correction.”

Anna lived another twenty years after sending that letter, and she filled them with the same sort of independence and keen intellect. She joined the Daughters of the American Revolution on the basis of her descent from Ephraim Brockway, who had served in militias at Saratoga and West Point during the war. As her marriage broke down in the 1890s, she had begun to write prolifically and to collect historical documentation of Michigan. Naturally, the Copper Country proved to be her chief interest. By 1926, the personal diary where she stored her compositions spanned over sixty-one volumes, a remarkable output for any author or diarist. She contributed extensively to “Michigan History” magazine and compiled reminiscences of her early days as a pillar of Copper Harbor. In the moments when she wasn’t occupied with her historical work, poetry for young readers came tripping lightly off her pen.

If passion alone could sustain a life, the world would not be deprived of great minds and vivid souls so early. Anna’s heart began to trouble her as she turned eighty. No doubt she noticed the problem early; perhaps she suspected the diagnosis herself, her medical training having become second nature. No doubt, as well, that she recognized when there was no hope. When Dr. Anna Medora Brockway Gray died on March 29, 1931, a life of independence and distinction came to a quiet end. She returned to be buried to the only place that made sense: to the Keweenaw Peninsula, to Lakeview Cemetery in Calumet.

A remarkable Brockway woman could not be laid to rest anywhere but the Copper Country.

You never know who is who in history until you study it. I lived many decades in , and was born in the U P and Brockway Mountain was just that, a mountain. I never thought about where it got its name. I am sure glad to be learning about this fascinating peninsula even at this advanced age!