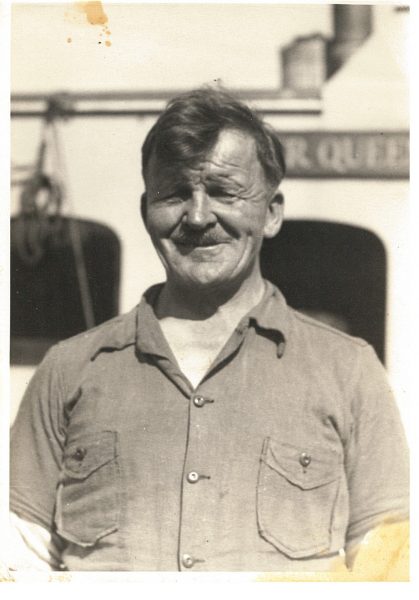

Charles Kauppi belonged on the water.

He hailed from Kuivaniemi, a parish of Finland with a lengthy stretch of coastline on the Gulf of Bothnia. A river cut the parish in two, flowing past a small, rural settlement that bore the Kauppi name.

Perhaps his draw to the water was evident at an early age; perhaps it began when Kalle, as he was known then, looked across the ocean toward the United States. He and his older brother, Juho Aukusti, set sail for Houghton in the company of several friends. They departed in September 1902, when Kalle was twenty years old. In those days, the journey from Finland to America was a long one. A Finn headed to the Copper Country would first take a ship to England, then wait for a transatlantic liner. He might land in Boston or New York; he might instead go north to Montreal or Quebec City, then journey into Michigan through Sault Ste. Marie. Kalle and Juho’s ship, the Celtic, deposited them in New York Harbor on September 29, and the two set off for Michigan.

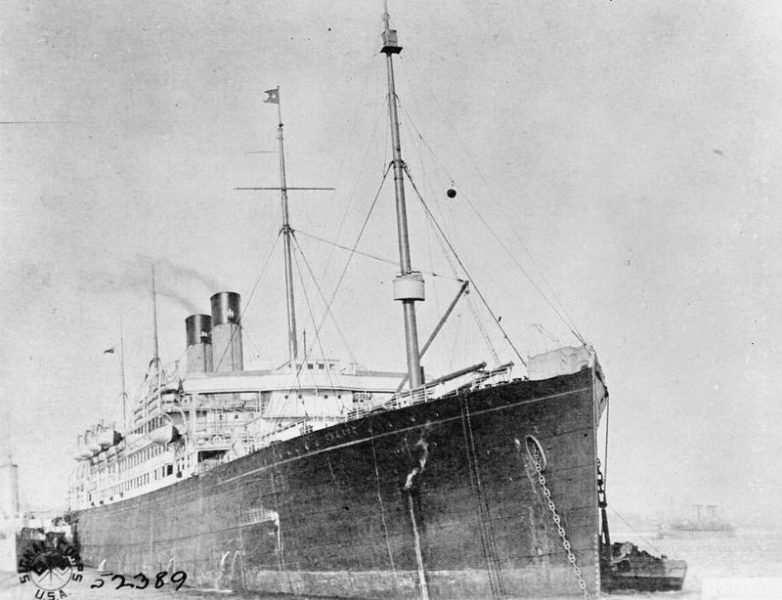

Many Finns came to the Copper Country in hopes of earning enough money to return home and buy a farm in Europe. For a variety of reasons–new comfort in the New World, more affordable land, the ardor of the journey–the number who actually made the trip proved far smaller than the group that hoped to do so. Kalle chose to file for American citizenship but had no qualms about crossing the Atlantic once again, even during difficult times of the year: February 1910 found him passing through Liverpool en route to Kuivaniemi for a visit. Six months later, he once again crossed the Atlantic, this time aboard the Virginian: the trip must have seemed almost routine by then. He landed in Quebec City, crossed the border as American citizen Charles Kauppi, and headed back to his new home in the Copper Country. He left the Baltic Sea of his childhood and the Atlantic Ocean of his youth behind, but an inland sea–Lake Superior–called to him.

When Charles Kauppi married Helena Lamberg, an early settler at Toivola and a fellow Finnish immigrant, on May 8, 1913, he gave his occupation as janitor. Increasingly, however, his work shifted away from mines and onto the waves. “On [a] Sunday morning” of unknown date, wrote Mac Frimodig in his Keweenaw Character, “while fishing with the Jaasko brothers at Grand Traverse, he ‘saw the sun come out of the lake’ and at that moment he knew his career in the mine was over.” By 1920, a census taker found the Kauppis–Charles, Helena, daughters Lyla, Leona, and soon Lilian, and son Willard–ensconced in “a log cabin with an unobstructed view of his beloved emerging sun” just north of the Keweenaw County village of Gay. Gay, with a Lake Superior shoreline reminiscent of Kuivaniemi’s gulf coast, provided a fisherman the ideal place to launch his craft and trawl the crystalline waters. As the location of the Mohawk Mining Company’s stamp mill, it also provided employment for Charles the mariner when winter settled over the lake, dimming his financial prospects.

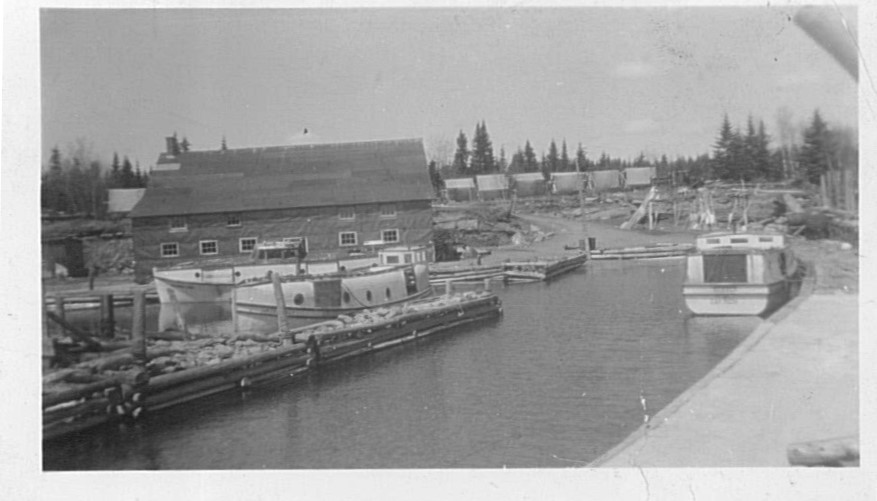

The Mohawk Mill closed in 1932, casting a pall over Gay. By now, however, the Kauppi family’s interests had turned even further away from the fortunes of the copper mines. Despite the looming Great Depression, tourists found Isle Royale–that long, rugged, forested island near the Canadian border–increasingly attractive, and Charles Kauppi recognized an opportunity. Why not offer ferry service to island-bound voyagers using one of his own vessels, the Water Lily? The boat might be better suited to fishing than to passenger service, with its cramped quarters and dark interior, but the captain soon known to all as “Charlie” carved out advantages nonetheless. By sailing from Copper Harbor, much closer to Isle Royale than the competing Michigan port at Houghton, Kauppi would reduce the time that passengers were on the water. He also applied his natural sisu and tendency for risk-taking to his lake journeys, venturing out on days when few others would make the trip. More on that later.

The Water Lily and her captain quickly found a toehold in the ferry world. Charlie began his Copper Harbor-Isle Royale journeys in 1930, give or take a year depending on the source consulted. Despite a number of challenges brought on by the Depression–what Don Kilpela, intimately familiar with the Isle Royale ferry business, later called “a normal man’s nightmare” in Lake Superior Magazine–Kauppi persevered. The news arrived in March 1931 that Isle Royale would soon become a national park, a decision that boosted the island’s profile and brought more passengers to Copper Harbor. By the middle of the 1930s, Charlie had outgrown the Water Lily. He commissioned a 48-foot long replacement named the Copper Queen, a lovely craft that cut a fine figure on the water and would seat far more people than her predecessor.

Unfortunately for Charlie Kauppi, his new vessel arrived at a time of increasing government regulations surrounding scheduled passenger ferries. The bulkheads below deck on the Copper Queen were not watertight, one of the new parameters, and the government rejected Kauppi’s application for scheduled ferry service. Over the next few years, he continued to run his charters, charging $5 per person for a round trip, and in 1938 took delivery of the Isle Royale Queen, a vessel that met government requirements. Regularly-scheduled passenger service between Copper Harbor and Isle Royale began that year, launching over eighty years of ferries. In the early days, when Charlie Kauppi was at the helm, the ride could be a wild one.

Lake Superior is capricious; its moods change on a whim. Children raised on the lake quickly learn to respect it and to know when to stay on land. Charlie Kauppi knew his limits, as well. They simply happened to be far beyond what most people would accept. Don Kilpela, in a blog post about the history of the ferry service, recounted a “probably apocryphal” story about the time that Charlie did finally put his foot down–or try to do so. In 1943, following an overnight layover on the island, Kauppi awoke, appraised the storm rolling in, and decided that he would not go out. The waves were some 14 to 18 feet high, enough to overwhelm larger boats than Charlie’s. One big city passenger, upon hearing that his trip back to the mainland was postponed, refused to accept it. He began to argue with Kauppi, who held firm until the passenger said, “I didn’t know that Finns had a yellow streak down their back.”

No one called Charlie Kauppi a coward and got away with it. He relented and agreed to take the angry passenger back to Copper Harbor, along with a handful of others. After an hour of merciless buffeting by the wind and rolling over waves that make one seasick just to imagine, the big city man begged Charlie to go back. He apologized. He pleaded. None of it worked: Charlie was too stubborn now to relent. To quote Kilpela:

Finally, the man asked, “Are we going to make it?”

Charlie answered, “We go as far as we can.”

And if that story was, in fact, apocryphal, countless genuine incidents proved Kauppi’s determination and skill on the water. January 1940 saw one of the more dramatic ones. Louis Baranowski, a native of Calumet, had been stationed on Isle Royale as a radio operator for the National Park Service. Winter surrounded the island, which gained a new sense of isolation as the snow fell and the parade of passing ships tapered off. In the midst of this, Baranowski received word that his father had died. Families belong together in times of grief, and someone wondered if there could be a way to bring Baranowski home to Calumet. The logical choice–the only choice–was to ask Charlie Kauppi.

The day that Kauppi set out from Gay, still his home, on the mission of mercy, a nasty blizzard rolled across western Lake Superior. Wind screamed through open cracks in cabins; visibility diminished; thermometers hovered near zero. Lighthouses at Eagle Harbor and Copper Harbor were relit in hopes of helping Charlie on his way. The Isle Royale Queen, carrying Kauppi and his future son-in-law Emil Wiitala, made slow progress toward the tip of the peninsula. As waves nearing 20 to 30 feet broke over the Queen’s bow, they froze, encasing the boat in ice. Kauppi and Wiitala pressed on, hoping against hope that the weather might break. Rounding Keweenaw Point, they realized that to continue was suicide. Kauppi wrestled the vessel into port at Copper Harbor, conceding defeat for once in his life. The beacons along the coast went dark. If Charlie couldn’t make it, no one could.

Charlie Kauppi ran the ferry for the rest of his days. The years between his acquisition of the Isle Royale Queen and his death proved to be eventful ones. After years of “extreme and repeated cruelty,” to quote the court documents, at the hands of his wife Helena, Charlie filed for divorce. His petition was granted on November 1, 1937. Ten years later, in his winter home of Grand Rapids, Charlie remarried. The new Linda Kauppi, a widow, shared her husband’s Finnish roots and Copper Country background. Charlie became a grandfather several times over, through his daughter Lyla and son Willard, and kept his love for the lake alive for as long as he drew breath.

In February 1954, Charlie Kauppi died at his Grand Rapids residence; he was 71 years old. Loved ones saw to it that a stone was erected in his honor at Hancock’s Lakeside Cemetery sometime later. Willard Kauppi sold his father’s boat and business to Ward Grosnick, who passed the helm to the Kilpela family upon his retirement in 1971. The Kilpelas operate the Isle Royale Queen IV to this day, keeping the sort of sisu and ingenuity that defined Charlie Kauppi a part of Keweenaw County tradition. Photographs from the Kauppi ferry service now reside in the Michigan Tech Archives as MS-898: Kauppi Family Collection.

Posts from Don Kilpela, Sr., on his Circumnavigating blog, as well as his “Lake Superior Magazine” piece (linked above) and Mac Frimodig’s book “Keweenaw Character” informed this post.

It just goes to show that SISU is not just our middle name, it is a way of life!! I never knew the history of the “Queen” and now I do, R*E*S*P*E*C*T the Finns for sure …Thank you archives for this history lesson

Wow!! Brought tears to my eyes – what an amazingly courageous person that helped define the true meaning of SISU & Yooper Strong!!!