Good times seem that they will never end.

When Calumet & Hecla was in its prime, the future seemed to promise unalloyed brilliance. The company was the richest in a district that produced 12 to 16 percent of the world’s copper between 1880 and 1910. The company “ruled its region,” historian Larry Lankton wrote, “with a haughty self-assuredness that the only way to mine for copper, or to run a mining community, was the C&H way.” In the late 1800s and early 1900s, C&H seemed vindicated. Although plenty of have-nots called the residential areas around its mines home, Calumet and Laurium also abounded with signs of prosperity. In 1900, the imposing Calumet Theatre, with its sandstone facade and a proscenium arch adorned with murals of the Greek muses, opened on Sixth Street. Pedestrians strolled along wooden sidewalks underneath a growing spider web of electrical wires. Shoppers could browse through a number of specialty shops, including photographers’ studios, multistory department stores like the Vertin Brothers, and jewelers. Multiple newspapers circulated in town. Presidential candidates campaigned personally in the area: Theodore Roosevelt stopped in Laurium to promote his 1912 third-party bid. Although no truth existed to later rumors that Calumet would be made the capital of Michigan, it was undoubtedly the capital of the Copper Country.

But no boom town lasts forever. Calumet’s star faded in the wake of the 1913-1914 strike, a post-World War I slump in the copper market, and later still with the onset of the Great Depression. In 1910, the population of Calumet Township was 32,845; by 1920, it had declined to 22,369, a decrease of more than 31 percent, as people sought jobs elsewhere. By 1970, the township had only about one-quarter of the population it had enjoyed at its peak. Even more notably, Calumet & Hecla had finally closed for good. Failure of employees and management to agree to terms on a new contract in August 1968 led to a strike that dragged into the spring of 1969. The company’s new owners, Universal Oil Products, ultimately elected to cease all mining operations. Although some hope remained of eventually dewatering the Centennial Mine, and some Calumet workers rode daily chartered buses down to Ontonagon County’s White Pine Mine, the era of mining had ended.

The profound changes wrought by mining and population growth remained, and so did the people who remembered and appreciated the Copper Country in its heyday. Local residents had long been passionate about history, forming societies and museums to keep their heritage alive even when the mines were still running. The Keweenaw Historical Society, under the leadership of John T. Reeder and John A. Doelle, began to collect archival material on the Keweenaw Peninsula in 1912. The Houghton County Historical Society, a successor organization, began in 1961; its counterpart in Ontonagon County dates to 1957. Yet appreciation for history as a means to keep the Copper Country alive reached greater heights after the mining period drew to a close.

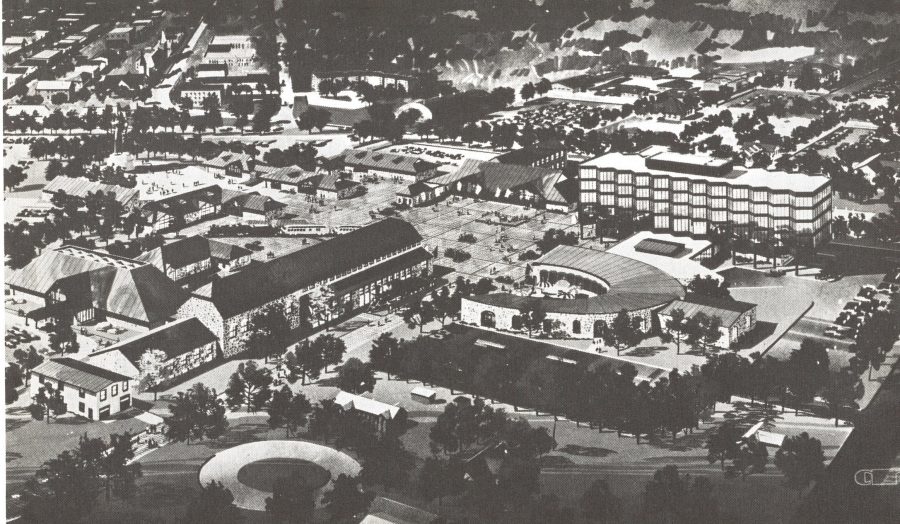

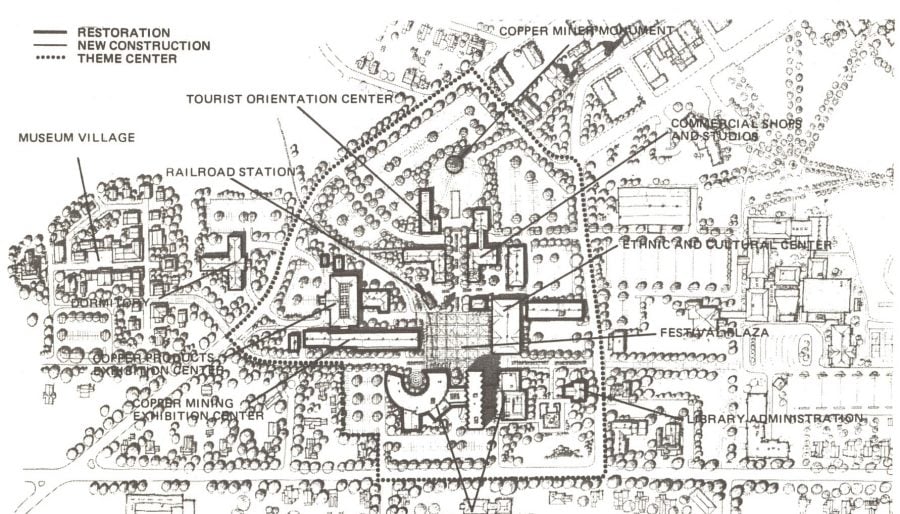

One proposal perceiving history as a means of revitalization took a particularly grand, sweeping, and in some ways eyebrow-raising approach. Its creators dubbed the vision “Coppertown U.S.A.” In an April 3, 1973 presentation in Calumet, Robert Teska, a representative of the project through Barton-Aschman Associates, described Coppertown as “a plan to restore and expand the former Calumet & Hecla headquarters… into a historic mining, ethnic, and tourism complex.” The project’s main purpose would be “the creation of a historic center and service facility for Copper Country tourism, to be entertaining and educational and to be integrated into the social and economic fabric of the two communities of Calumet and Laurium.” Ideally, Teska explained, Coppertown would span “in excess of 300 acres overall” across the heart of the old C&H properties, with its center “ideally located at the historic crossroads of U.S. 41 and Red Jacket Road.”

The Coppertown U.S.A. complex proved broad not only in scale but in scope. Teska laid out a plan for multiple “development units” surrounding the “theme center.” The heart of Coppertown would host parking for well over 1,000 vehicles. Mine Street, the road along which so many shafts had been dug, would become a pedestrian path along which tourists could stroll. Behind the former C&H library building–serving as administrative headquarters–Barton-Aschman Associates envisioned the old roundhouse transformed into an entertainment megaplex, in conjunction with a newly-constructed motel. There, visitors could dine, browse boutiques and art galleries, pick up drug store necessities, or take in a musical performance. While most of Coppertown had a tourist orientation, the roundhouse would be designed as a gathering place for locals, as well.

The theme center was just the start. A second development unit incorporated “several satellite activities” of diverse types. A museum village consisting of “10 to 15 authentic buildings moved to the site from [throughout] the Copper Country and restored to reflect a period in history” would sit adjacent to Mine Street. Teska’s presentation suggested that the village might consist of a general store, church, schoolhouse, blacksmith shop, and “several residences that would typify the homes of early miners and of various ethnic backgrounds.” Summer employees and school tour groups traveling from a distance would bunk down in a special dormitory built for their use. When they ventured out beyond the roundhouse and museum village, they would find a host of activities devoted to copper mining awaiting them.

Recognizing the popularity of the Arcadian Mine in Ripley–and presaging the success of Quincy, Delaware, and Adventure–the Barton-Aschman proposal for Coppertown U.S.A extensively incorporated demonstrations of mining technology, techniques, and properties. “The highlight of the satellite activities would be the Osceola Mine,” explained Teska, “a modern facility that would be restored for use as a major attraction offering an underground tour of an actual copper mine.” Tourists visiting Osceola could hop aboard “a small historic mining train,” sure to delight children and adults alike. Later, back on Mine Street, they would find Coppertown’s exhibition center, “an entertaining and educational display featuring the history of copper mining, the technology used, old equipment, and demonstrations of actual mining and maintenance techniques.” From there, the visitors would stroll through another hall displaying new copper products. If they tired of studying copper mining itself, the Coppertown ethnic and cultural center would provide them the opportunity to learn more about the cultures of Keweenaw people, both immigrant and indigenous. “The center would be a place where ethnic crafts and food would be made and sold, Teska said, “where people of all ages would come to participate in authentic folk music and dancing, and where the joys of folklore would prevail. Employees would be dressed in costumes representing their native homelands.” Folk culture would spill out into the “festival plaza,” a decorated outdoor space that would be “a focal point of community as well as tourist activity.”

Crowning the entirety of Coppertown, “several hundred feet to the northwest” of the festival plaza, would be a statue of a miner standing some 70 to 80 feet tall. If Keweenaw Bay had its shrine to Bishop Baraga, then Calumet would have a monument to the industry that built it.

Of course, none of this–the renovation of Osceola, the construction of a new motel, the commissioning of a copper statue–would come cheap. Barton-Aschman estimated that, in addition to land, Coppertown U.S.A “will require… a considerable investment of approximately 12 million dollars.” In 2019, an equivalent investment would total over $70 million. To assuage anyone who balked at the high price tag, Teska promised that Coppertown would quickly pay for itself, bringing droves of visitors to the Keweenaw with money to spend. The statistics presented by the consulting firm were staggering: one million visitors per summer to the area by 1980, with as many as 850,000 people–both locals and tourists–stopping in at Coppertown. Each summer, the Barton-Aschman presentation said, Coppertown would lead to a gross income of over $5 million; winter tourism would be the icing on the cake. In addition, the complex stood poised to bolster local tax revenues, employ a populace that could no longer look to the mines, and unify Calumet and Laurium.

At the time that Barton-Aschman Associates presented the plan for Coppertown U.S.A, it must have seemed like a marvelous and realizable dream to its boosters. If the inspiration and funds of Henry Ford could bring Greenfield Village to life, why could the people and companies of the Keweenaw Peninsula not do the same? Supporters who signed on to the plan early on included Endicott Lovell, a former president of Calumet & Hecla, William Nicholls, vice president of the Copper Range Company, and Louis Koepel, who had charge of the Quincy Mining Company property in Hancock; joining them were prominent local contractor Herman Gundlach, multimillionaire philanthropist and Laurium native Percy Ross, and historian Arthur Thurner, among others. Although some local residents, despite fundamental agreement with developing tourist appeal in the region, expressed skepticism of the project, its Copper Country directors set up in the old Calumet & Hecla library building with great anticipation. Promotional literature brimming with optimism scurried through the post offices and into newspapers across the state, and a sign proclaiming Calumet the future home of Coppertown went up on the edge of town.

Yet the project’s grand scale proved to be in large part its undoing. Despite the support of millionaires and bank executives, the $12 million needed for that initial investment was difficult to raise. By 1975, although the dream remained alive and its board active, some reductions had already been made. A newspaper article describing the aim of Coppertown described the would-be iconic miner statue as standing some 35 to 40 feet, only about half of its original intended height. Plans for the motel, the roundhouse shopping complex, and hauling historic buildings from their homes throughout the Copper Country stalled. In 1979, the old Calumet & Hecla pattern shop opened as a museum and visitor center for the future project.

By 1980, however, local newspaper the Copper Island Sentinel wrote that Coppertown was highly unlikely to come to fruition as originally planned.

“According to the original plans, Coppertown was to be a complex of buildings, including a hotel, library, cultural center, 70 foot statue and plaza area that would accommodate 650,000 tourists a year. Those plans have yet to be totally abandoned, unlike the mines it was to hold in tribute. But the reality of the present is those future dreams rely on the 14 women of the Coppertown Auxiliary and the profit margin of a small boutique that supports the only operating attraction of the development–the Coppertown Museum.”

Despite the best efforts of the auxiliary women and those who staffed the pattern shop, the Coppertown U.S.A project went no further than that. However, a little over a decade after the Sentinel piece, a different effort to organize, preserve, and promote the Copper Country’s historic resources saw its hopes realized. Keweenaw National Historical Park was officially established on October 27, 1992. Although its approach to tourist facilities proved quite different than its predecessor project, the new park shared certain values with Coppertown: a passion for a special past, a devotion to revitalizing mining towns, and a desire to share the ethnic treasures of our community with the world at large. Today, the Coppertown U.S.A museum remains in operation as a long-term member of the Keweenaw Heritage Sites network of the national park. Long after the mines have faded, the heritage left behind is more vibrant than ever.

A wonderful window into yesterday this provides! AND debunking the rumor of moving the capitol . Personally I found this good reading…….