When Alfred Nicholls came to Central Mine from his native Cornwall in May 1880, he confessed himself “not very favorably impressed with America,” including Central. Central would prove to be a place of great tragedy, perseverance, and triumph that changed his life in ways he never imagined. In finding Central Mine, Alfred Nicholls found his home–and himself.

Alfred arrived in the family of William and Mary (Northey) Nicholls on May 3, 1861. Born in or near Kenwyn, Cornwall, he grew up surrounded by six siblings and the distinctives of Cornish society: mines, Methodism, and music. William Nicholls “was the foreman blacksmith at Nan Giles mine,” Alfred wrote in The Story of My Life, the memoirs he prepared for his children. “In that same shop he worked forty consecutive years. During that period he never lost a day because of sickness.” Mary, meanwhile, was “quite tall, muscular and an endless worker. I do not remember ever hearing her say she was tired. The care of her children was above everything in her life. Though kindly disposed in the affairs of life generally, she had snap and fire if driven to it.”

The Nicholls home was a warm and welcoming one, with Mary bustling around to care for the children and William always available to hear out their worries. He provided the example to which his son always affectionately aspired. “Very early in life,” Alfred recalled, “he took me by the hand and led [me] to the house of prayer. To this day I am truly thankful that he directed my steps in the paths of rectitude, the Paths of Life.” As soon as he was old enough to join the Primitive Methodist Church, his parents’ congregation, Alfred did. From an even earlier age, he was involved in its music. The Cornish enjoyed an international reputation as passionate and gifted singers, and their tradition of vocal music extended to work, church, and home. The Primitive Methodist choir regularly practiced at the Nicholls house, and Mary would “flare up rapidly if a member of the other church [Wesleyan Methodist] became too boastful of her choir.” Alfred first helped blow the bellows of the pipe organ for the choir until the joyous day when his voice was strong enough to admit him as a singer. He also turned pages for a church flautist and expressed a firm conviction that, one day, he would be the instrumentalist cueing a little boy to find the next page.

Although the paths of most Cornishmen led them to the mines, they passed first through the small schoolrooms of their various villages. Alfred began in the small private school of a teacher called simply “Miss Jane,” where a penny each week paid his tuition to learn the alphabet. When he grew older, he attended a government school where discipline was strict and corporal. After one particularly vicious round of punishment, Alfred’s parents noticed their bright son’s spirits flagging and transferred him to a church school whose teachers were not so quick and ruthless with the rod. He remained there, contented, until the age of nine.

One day, “when I was almost ten years old… John, my brother, came home one evening from the mine with the good news that he had gotten a job for me at the stamp mill at the Wheal Jane mine.” Alfred’s parents decided it was time for him to go to work–not from financial necessity, as William Nicholls earned enough to keep the family, but more in keeping with the custom of the community, which sent most boys to work at a young age. After all, “I could read, write and cipher, what more was needed?” He began packing a pasty and walking to the mine for twelve-hour days or nights–a pattern that he expected to continue for the rest of his life. Happily for music-loving Alfred, a subsequent supervisor at the nearby Wheal Peever mine gave him permission to skip the occasional shift and perform with the brass band he joined as a teenager.

Although the Cornish mines were still producing in Alfred’s childhood, their riches had begun to run out. His older brothers, like so many other men of their generation, began to look abroad, across the Atlantic Ocean to what Alfred called “the Land of Promise.” One by one, the Nicholls boys purchased passage to the United States and “[left] the fireside in successive years, possibly never to return.” In 1880, nineteen-year-old Alfred borrowed the money to buy his own ticket. He would join his older brother, Dick, and Dick’s family in the thriving town of Central Mine, Keweenaw County.

The day he departed Cornwall remained vividly etched in Alfred’s mind. Carrying a new carpetbag, he walked the mile to the train station. “It was Maytime and all nature gorgeously arrayed. Primroses were in the meridian of their charm and glory. Soaring above till lost to view, the lark carried up and up its enchanting note of warbling song. My heart was strangely touched.” As first Kenwyn and then his native land faded away behind him, Alfred mourned. “Then, alas, came the last glimpse of home! Ah, the memories, the friends, the tears! England, my country, my home, I loved most dearly! It was home and represented all the endearing charms that word implies.”

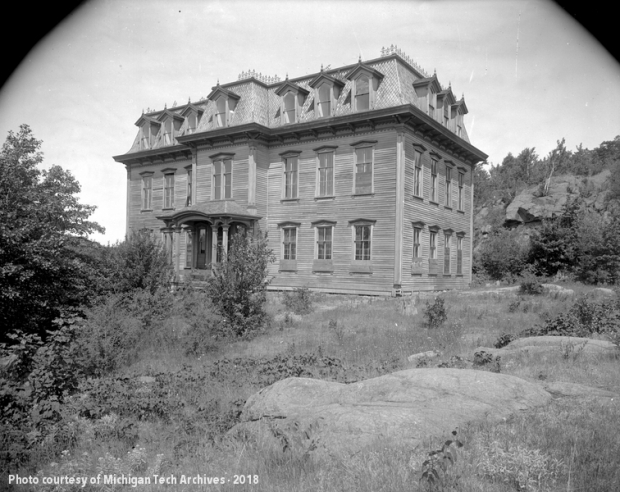

Central Mine, his trade for England, disappointed him at first sight. Three and a half weeks of hard travel by land and sea brought him to this place in what felt like wilderness, a place oriented more around mining than Cornwall had ever been. “Such tiny log houses, no streets, no shops, no social activities,” Alfred cried. “Not much of anything except work. Well, I was accustomed to that.” Determined to make the best of his situation, he applied for a job as a miner, the first time he would be laboring below the ground. The adjustment proved difficult. Although Alfred was eager to learn, becoming efficient and capable as a miner was an uphill battle. He heard people refer to him as a greenhorn, “which tormented me terribly. Our family were respectable, and could look the whole world in the face. My interpretation of that term suggested inferiority, a lower strata of the common people. I detested the word.”

Alfred found solace from misery in his beloved music. Within days of arrival, he received an invitation to join the choir of the Central Mine Methodist Church. He accepted eagerly and began to attend rehearsals at a nearby home. With darkness falling after one rehearsal and livestock permitted to freely roam Central’s rocky roads, his hostess suggested that a member of the soprano section needed an escort home. Would Alfred be willing to assist? “I was anxious to become an American, to acquire their customs, to acquaint myself with such duties of etiquette as are becoming to young men,” Alfred said. “The proposal to accompany her home had been suggested, and the only thing, the courteous thing, was to say it would become a pleasure indeed to do so. The young lady offered no objection, and into the darkness we followed a path that led to her door.” A friendship formed on that day, friendship that soon led to something more. On September 1, 1883, young soprano Eliza Carter Chinn became Alfred’s wife.

The newlywed Nicholls settled down in Central, and their lives seemed hopeful. Alfred was proud that his hard work and his wife’s determined thrift allowed them to purchase their furnishings in cash; they even came up with enough to buy an old organ that the Methodist Church was replacing and still had money to stash away in a cigar box. Their house was small but full of love and music, and his connections with Eliza’s family and the church, almost all of whom were also of Cornish descent, helped Alfred to acclimate. Gradually, Central Mine began to feel like his community. Life there was simple and peaceful, and the birth of a daughter, Mildred, in 1884 crowned Alfred’s new home with joy.

“Then came a day when the heavens darkened, and in torrents the rains of adversity descended! In a moment, like some terrible thought fashioned in a dream, my life became one of unutterable sadness and depression. The austere hand of adversity came into our home, and my days and nights were of unfathomable blackness.”

Fifty years later, Alfred’s emotions when he remembered his injury remained strong and agonizing. Mildred was seven months old when he walked to the mine for his typical daily shift. In the course of his work, Alfred sustained a grievous fracture to his left arm at the elbow. Doctors treating him made the devastating choice to bind him up tightly from hand to shoulder, believing that his broken elbow would grow stiff without this support. Instead, they cut off circulation to the area. Thirty-six hours later, when these same doctors cut the wrappings off, Alfred’s arm rapidly swelled to twice its size. From the elbow down, he lost all sensation and muscular strength, and they never returned.

“The question of compensation or liability was unknown,” Alfred said. “We accepted injury as an unfortunate experience and the consequent burden to be personally assumed.” But after he regained his strength, he found himself at a loss. He could not mine any longer, and most aboveground tasks at the mine required two able arms. The exception was the role of dry man, a position “usually performed by an old man unable to do strenuous labor” and whose primary responsibility was “to spread all wet mining cloths near steam pipes and dry them thoroughly for the next shift.” Central Mine had all the dry men it needed, and Alfred’s pride rose up at the very idea. “I was too young in life and my ambition for something better would not permit it.”

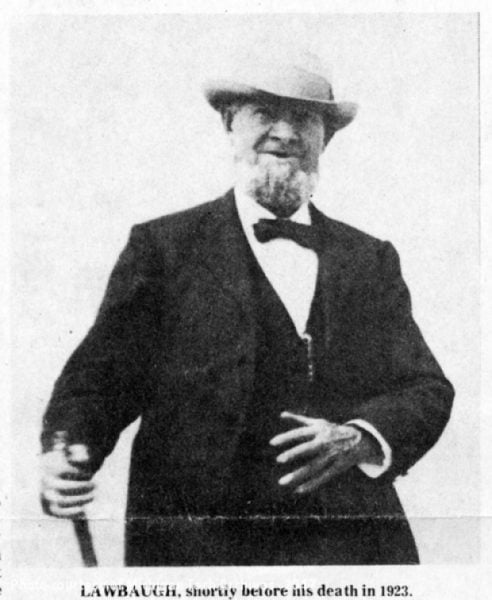

For the next few years, he struggled. Miners at Central had formed a benefit society for injured and disabled men, and Alfred drew a dollar a day from that for the first year. He also relied on funds provided by Court Robin Hood, a lodge of the Ancient Order of Foresters fraternal organization to which he belonged. Eliza’s persistence in finding ways to stretch their money and cut costs got them through the slim days, but Alfred could not be content until he knew the family’s path forward. Doctor after doctor, including specialists in Ann Arbor, encouraged him to keep his spirits up and try therapeutic exercises in hopes of regaining function. Finally, a Dr. Lawbaugh stationed at Osceola gave him the truth with brutal abruptness. “Breathlessly I awaited his diagnosis. In a few moments he said: ‘You will never use it again, my son.’”

Anguish tore through Alfred. “The heartaches, the tears, the agony… no words can adequately express my pangs of suffering during that hour. Surely this is my Garden of Gethsemane.” He walked the streets of Osceola in darkness, wrestling with the news and with his faith. At the boardinghouse where he stayed the night in Calumet, he could not join in with the Cornish merriment and music. He lay awake, realizing that he would not play the pipe organ or the flute in his family home again, and praying for relief from his torment. When some at last came, he rose and boarded the stagecoach toward Central. Only one other passenger occupied the humble vessel: another Cornishman, bound for Phoenix, with no vision and a single arm. The two commenced to speaking of their injuries, with Alfred listening at length to his companion before recounting his own story, desperate to unburden himself to someone who might understand. Instead of sympathizing, the man fell silent.

“He waited a few moments, then slowly, distinctively there fell from his lips these words: ‘Well, my son, I don’t know you, have never seen you, but if I were as well off as you physically, I would ask for nothing more. My joys… would be complete.’”

Alfred said that the words “burned into my very soul.” Immediately, his attitude transformed. With his accident and the malpractice that followed, he had lost something, yes, but he had not lost everything. He had been spared more than some and determined not to dwell on what had been taken from him. Arriving home at Central, he embraced his young daughter and “felt keenly the responsibility of parenthood resting upon me.” Holding Mildred close, “I made another vow, with all the force and determination at my command: that in any future enterprise I decided upon to undertake, no sacrifice should be too great to endure, no effort too strenuous, no barrier too mountainous to overcome that my baby’s future be deprived of life’s fullest opportunities.”

A few false starts to find a new career in peddling or telegraph operation did not defeat Alfred but left him sorrowful. After another difficult day, he and Eliza discussed the advantages and disadvantages of his options. Then inspiration struck. “Why don’t you go to college?” Eliza asked.

“What’s the use of a blockhead like mine going to college?” Alfred responded skeptically.

“Just as much as any of the other blockheads who go,” Eliza shot back, “but they don’t come out blockheads.”

Alfred was flummoxed at first, but the idea gradually began to take shape in his mind. His academic accomplishments were limited, and he knew nothing of American geography or history, let alone how to study. He felt too wide a gulf of knowledge existed between him and the Central schoolmaster, whose mere presence reminded him of the brutal teachers of his youth, to approach him. He decided first to apply himself to home study, gradually gaining confidence in arithmetic and penmanship. When a new school principal arrived in Central, a more capable Alfred Nicholls walked up to the schoolhouse to introduce himself and explain his goals. With this man’s permission and the blessing of the president of the school board, he enrolled alongside the fifth- to ninth-grade students.

Seated in the rear of the room, Alfred became a student not only of grammar, history, and physiology but of adolescent psychology and pedagogy. “Much of my time was devoted to observation. It afforded an unusual opportunity to study the different characteristics of the student body… I discovered the adolescent period of youth, youthful vicissitudes, and perplexities, were not radically different from those of my childhood.” The three years that he spent learning alongside the teenagers of Central led him down a path he never would have anticipated: he decided to become a teacher.

Supported by his wife and by his lodge, Alfred enrolled in the Michigan State Normal School at Ypsilanti in September 1887. Eliza and their two children remained at home for his first year but followed him afterward. The path was fraught with challenges, and Alfred confessed that he sometimes felt the darkness of despair creep over him as he compared himself to his classmates and struggled with the work. “There is no prize for the halfway runner,” he reminded himself, and steeled himself to continue. He persisted through summer school and difficult examinations, including ones that he failed and attempted again. Finally, finally, he passed the last test. As he walked back to his rental home, Eliza stepped into the doorway. “As soon as I caught a glimpse of her, I threw my hat into the air, which she understood implicitly. Tears of joy came to both of us; our hearts overflowing with happiness words fail to adequately express. The trials, the hardships so long endured were lost in the joy of accomplishment. We were in a new world.”

The new world took him home. Hearing from Dick Nicholls that his younger brother had just received his lifetime teaching certificate, the Central Mine superintendent asked whether Alfred would be interested in serving as the school’s principal. “Ah, the joy untold! It was more than I could contain.” He returned in triumph. His worries about providing for his wife and children were at an end. Though the Nicholls family returned penniless, having spent all their savings to put Alfred through college, “we were proud, beyond measure… we could look the whole world in the eye, for we owed not any man.” When he walked into the Central school for the first time as principal, rather than pupil, no doubt Alfred’s pride and happiness reached heights that the downtrodden man of six years earlier could not have fathomed.

He remained five years at Central Mine, which was then in its sunset years. In 1895, seeing that his beloved community was going the way of Cornwall, Alfred accepted a position as principal at the Osceola school near Calumet. While there, he began correspondence work toward a bachelor’s degree in philosophy, proudly completing his course of study after five years. In recognition of his capability in teaching and leadership, stakeholders of the local schools promoted him to local district superintendent, then to township superintendent. He had earned their respect a hundred times over.

Alfred Nicholls died at his home in Laurium on August 21, 1944, following retirement and several years of poor health. Predeceased by his beloved wife, he was survived by those to whom he had given so much of himself: his six children, the schools of Osceola Township, and the annual reunion of Central Mine, which had been his brainchild.

No one could ever say that he was a halfway runner.

All quotes in this post were taken from Alfred Nicholls’s “The Story of My Life,” his memoirs.

Well researched and masterfully written! The kind of story that makes the merchants eyes water. Thank you