It was the boss’s house, the boss’s rules, and the boss’s style.

Michigan’s copper mines regularly provided housing to their workforces. Indeed, a company who did not offer dwellings felt itself at a disadvantage in trying to attract workers. Thus row after row of homes arose in the shadows of shafthouses, echoing quietly with the sounds of the mines. Early log cabins gave way to more sophisticated frame homes, ranging in size from substantial double houses (duplexes) to compact “trunk houses,” so called for rooflines that mirrored travel trunks of the day. A worker could step out his front door, look right and left, and see a street of homes virtually identical to his own. The Quincy Mining Company even turned to Sears & Roebuck, a pioneer of kits that allowed the same house to be erected around the country, to design and manufacture homes for its workforce, adding to the uniformity of neighborhoods.

A company house, if inhabited by family or friends, could easily become home, but it wasn’t necessarily a luxurious abode. The structure might be larger than a worker’s dwelling in the old country, but it seems cramped by today’s standards: two bedrooms, perhaps three, to house a burgeoning family. Boarders taken in to make ends meet strained the house further. Companies afforded little room in these modest floorplans for amenities like closets and bathrooms. As of 1912, according to Alison K. Hoagland in Mine Towns, about half of Calumet & Hecla’s housing stock depended on privies. C&H employees wrote to the company on an individual basis to request indoor flush toilets, citing the unpleasant proximity of outhouses to kitchens in the summer or an infirm family member who struggled through snow in the winter. If the municipal sewer reached as far as the worker’s home, C&H often granted such requests by installing a basement toilet. With space at a premium and the company’s generosity decidedly finite, bathtubs or showers were much harder to wrangle. Workers instead hauled tubs into their kitchens or visited C&H’s public baths.

The story was a little different for the men in the corner office.

Alexander Agassiz’s connection to Calumet & Hecla was forged in the mid-1860s, when his brother-in-law Quincy Adams Shaw invested in a friend’s mine far from their Massachusetts home. But Edwin Hulbert, Shaw’s buddy, was no mining engineer, no businessman. Just a few years into exploiting the Calumet conglomerate lode, one of the world’s richest, Hulbert floundered. As Agassiz wrote in 1867, “The value of the mines… is beyond the wildest dreams of copper men, but with the kind of management many of the mines have had, then even if the pits were full of gold, it would be of no use.” In short order, Hulbert was out; Agassiz and Shaw were in. Agassiz would remain in, rising from superintendent to president in 1871, for the next four decades.

Although his word was law at Calumet & Hecla, Agassiz spent very little time in Calumet itself. After a few years of trying, and eventually succeeding, to get the company running productively, he returned to the East Coast. Splitting his time between overseeing C&H at a distance, studying natural history, and building a zoological museum at Harvard University, Agassiz built a luxurious existence for himself. He constructed a turreted summer home on a private cove in Newport, the opulent sanctuary of the extravagantly wealthy, and eventually made it his primary abode. He ventured out from New England to the Copper Country twice annually, looking over the mine and conferring with his lieutenants. Although Agassiz’s visits lasted only a week or ten days at a time, he felt that he needed a residence in Calumet, as well.

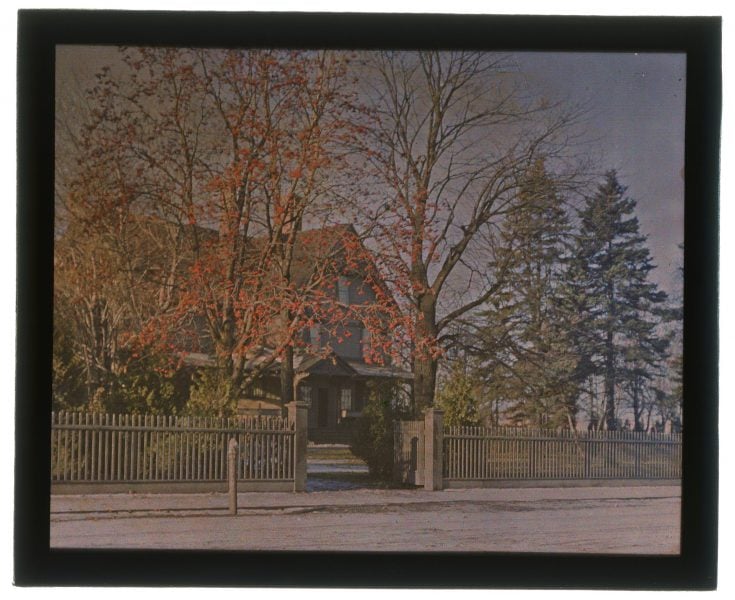

The company house that Agassiz received sat only a handful of steps from C&H’s main office and across Red Jacket Road from the eventual site of its library. Built well into his presidential tenure, the building stands as of 2021. A poor-rock foundation testified to the home’s local origins and tied the president to his mine. The house received renovations under subsequent presidents–like Rodolphe, Alexander’s son–but its core design elements remain discernible: gables, at least eight fireplaces, and a substantial footprint for a home only sporadically occupied. One wonders what blue-collar laborers, en route from a cramped house to a long shift, thought as they passed the darkened, unused building in winter.

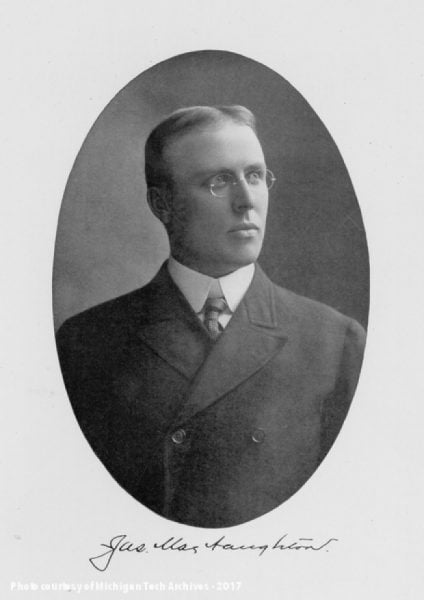

General Manager James MacNaughton was the ranking official on site and second to Agassiz in authority. If the company were willing to give Agassiz a substantial house for his visits, it’s hardly surprising that MacNaughton received an extremely comfortable dwelling of his own. Like Agassiz’s home, MacNaughton’s residence was situated in the midst of C&H’s operations. If the manager stepped off his property and crossed Mine Street, he stood before Hecla No. 6; across Calumet Avenue, east of his yard, he could scrutinize the activities at Hecla No. 14. A short stroll along Mine Street south of his Division Street boundary or north of his Agent Street frontage took him to various C&H shafts, compressor houses, engine houses, and other industrial buildings. For a man totally consumed by his corporation, no location could have been better.

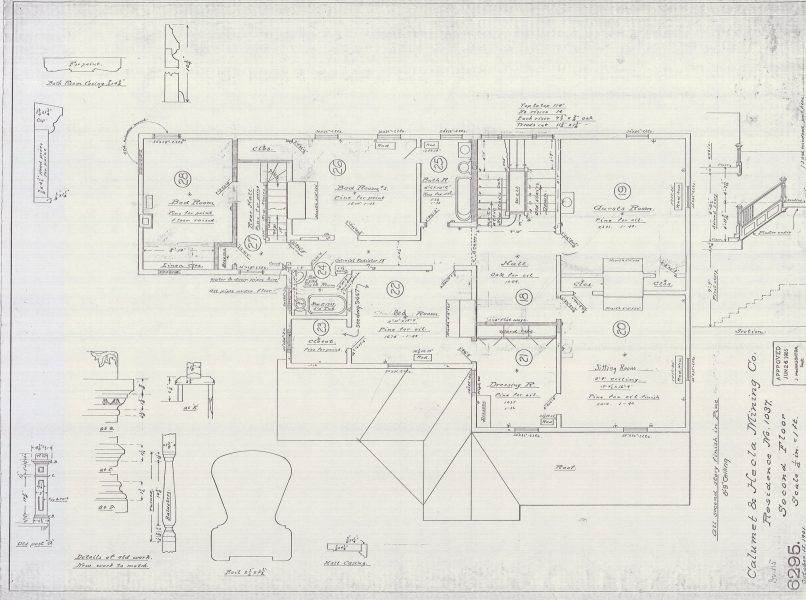

And the home itself, aside from its proximity to the mine, provided perks that MacNaughton enjoyed–and dictated. Hoagland noted that the house inhabited by his predecessor S.B. Whiting had been constructed as an L with roughly five rooms per floor. In home as in business, MacNaughton had grander visions and ordered an expansion to the house that fit his ideals. The 1901 redesign, conceived early in MacNaughton’s time as general manager, incorporated a sprawling porch that led guests into a vestibule and reception hall. At right, a living room warmed by fireplace and radiators spanned the width of the house–nearly forty feet. At left, a library with window seat offered a cozy reading space. Built-in cabinets in the dining room allowed for the display of dishes hosted in the adjacent china pantry.

A wooden staircase wound from the hall upstairs to family and overnight guest quarters. Downstairs, oak trim predominated; upstairs, softer pine hues took precedence. A large guest room, with its own sink, stood immediately off the stairs. Bedrooms for the two MacNaughton daughters, Martha and Mary, lay down the hall and to the right. MacNaughton and his wife, another Mary, shared a substantial master suite with a walk-in closet, a large dressing room, and a broad sitting room, all warmed by radiators.

Of course, there were bathrooms: bathrooms with running, heated water and state-of-the-art plumbing. A lavatory on the first floor, tucked underneath the stairs, serviced dinner guests. Upstairs, deep bathtubs gave father, mother, and daughters the chance to soak in warm water on January days. There would be no public baths and no basement toilets for James MacNaughton.

The third floor, a half story, housed storage and live-in servants employed by the MacNaughton family. As of 1910, the general manager’s household relied on a maid, a man-of-all-work, and a governess for Martha and young Mary. A decade later, at the 1920 census, the MacNaughtons–now expanded to include Martha’s husband Endicott and their son–had hired three female servants, a cook, and a butler. In 1930, the widowed James MacNaughton lived in his house with no one he did not employ: a butler, a cook, a laundress, and a chambermaid.

Whatever their interactions with MacNaughton as a person might have been, the house offered his employees modern facilities for their labor. Laundry was done on the first floor, off the large kitchen. A pantry and pot closet supplied the work of the cook. Most handily and luxuriously of all in the early 20th century, the expanded floor plan provided a large room for a refrigerator. With this and the ice house on the rear of MacNaughton’s property–near the garage–there was no worry of food spoiling. In the few odd moments when the maids and cook were not bustling, a sitting room positioned between the kitchen and dining room afforded them a few minutes to rest.

Unlike Agassiz’s home, MacNaughton’s did not survive the decline and fall of Calumet & Hecla. The building was razed at some point after his death and modern mid-century homes built in its place. The garage survived, however, alongside the countless smaller houses built by C&H for the common man–now complete with bathtubs.

Hey the same thing goes on today Eh? Very interesting and nice to see the home layout Thanks be to da archives for this