Dominic and Mary Vairo were in their kitchen when they heard the commotion upstairs. The voices were loud, insistent, emotional. Had a fight broken out? With tension palpable in town, fisticuffs even at a party would surprise no one. Worse–as Dominic listened closer to the cries–was it a fire? A fire kindling on the second floor would put much in Dominic’s life at risk: his business, his home, his family. He left Mary and their son in the kitchen and hurried to investigate.

Like many of his neighbors and guests of the party up above, Dominic’s origins lay far from the Copper Country. He was born to Domenico Emmanuele and Maria (Gianitti) Vairo in Italy’s Piedmont region in 1889 and spent at least some of his childhood in Locana. Forested hills rose high above Locana and the quiet valley along the Orco, a river famed for gold-bearing sand. For Domenico, Sr., however, the promise of gold beckoned from elsewhere. In 1893, he sailed to the United States to join his brother, Vincenzo, in the town now called Calumet. Calumet’s preeminence among Copper Country towns was already cemented, and its tired laborers longed to slake their thirst at local watering holes. By 1900, entrepreneurial Domenico had established himself as a successful saloonkeeper at the corner of Sixth and Oak streets, with boarders adding to his income. America had treated him well, and he filed for citizenship in the Houghton County court.

In 1901, after nearly a decade of separation, the elder Domenico returned to Locana to retrieve his family. The Vairos–mother and father, twelve-year-old Domenico, Jr., his older sister Maria, and younger sister Francesca–landed in New York City on October 26. Passing inspection at Ellis Island, they traveled to their new home at the heart of Calumet. Perhaps the departure from Locana had been a welcome one; perhaps Maria and her children mourned their native country with each mile they put behind them. No doubt they found in the Copper Country’s trees and Calumet’s vibrant Italian immigrant community some remnant of the land they had known.

Domenico grew to maturity in Calumet, learning the art of saloonkeeping alongside his father. Each adopted the English translation of his given name and became known as Dominic Vairo. The younger Maria would be called Jennie by her Michigan friends. Unfortunately, tragedy soon marred the Vairos’ lives. Francesca died on July 17, 1902, and her grieving parents buried her at Lake View Cemetery with a monument recalling her as their “little angel.” Illness crept into the family home a few years later: Dominic, Sr., and Jennie both contracted tuberculosis. Though the disease was a familiar one–Houghton County experienced higher tuberculosis cases than almost anywhere in Michigan–being commonplace rendered it no less fearsome. Fresh air offered the only hope of fighting the plague, and the two patients, accompanied by Maria, said their goodbyes to Dominic, Jr., in 1908. Just eighteen, he took over the saloon in his father’s absence. It was to be a permanent one: Dominic, Sr. died in April 1909 in Italy, a matter of weeks after Jennie.

The remaining Dominic Vairo faced a choice. He could go back to his native land and create a new life in an old country, or he could continue to build the business his father had started in America. He chose to remain in Calumet, filing an application for his own saloon license in 1910. From there, life took on a brisk pace. In 1912, Dominic moved his business from the Portland and Sixth intersection to the first floor of a newer building near Seventh and Elm. The structure had been rebuilt twice following destruction by the elements–first by wind, then by fire–and this time was equipped for style and safety. Dominic claimed the southernmost of the two storefronts and hung a modern sign reading VAIRO above it. A recessed doorway, with massive windows on either side, led into the roomy saloon. Curtains covering the lower halves of the windows gave the bar privacy, but Copper Country sunshine flooded through their upper halves. Like many merchants and hospitality providers of the time, Dominic resided in the same building, taking an apartment at the rear of the business. With the assistance of a new business partner, Frank Rousseau, and Dominic’s willingness to illegally open on occasional Sundays, the relocated Vairo saloon made a brisk start.

Dominic soon forged a more significant partnership than his one with Rousseau. He and twenty-year-old Maria (Mary) Perona fell in love. Like Dominic, Mary had come to Calumet from Italy and became involved in the local immigrant community. Dominic proposed, and the two married at Saint Mary’s, the Italian Catholic parish, in the afternoon of January 30, 1913. The reception was held that evening in the ballroom above Dominic’s business. After the festivities concluded, Dominic and his new wife walked down the stairs of the Italian Hall to their new marital home.

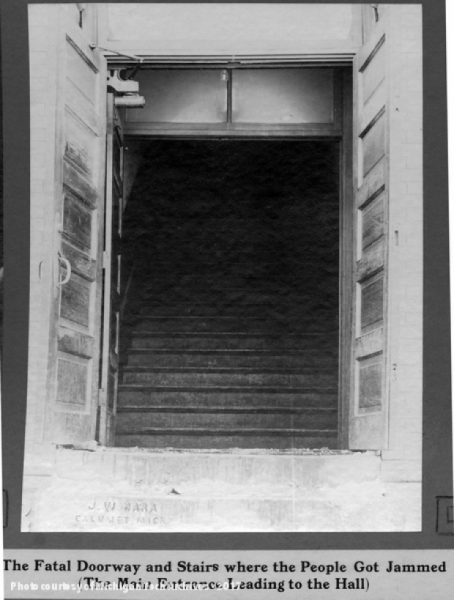

The Vairos were busy in the kitchen of that apartment, underneath the popular gathering space of the Italian Hall, on December 24, 1913. Their seven-week-old son, another Dominic, would celebrate his first Christmas, and no doubt the new parents felt sentimental. But the commotion above their heads shattered an idyllic evening. As Dominic rushed outside through the shed attached to the rear of his apartment, he found terrified partygoers plummeting onto its roof. Hearing more clearly now the calls of “fire!” he hurried back through the apartment to the front stairwell. A secondary door, adjacent to the infamous double set, opened from there into his saloon. He or Rousseau, who had been playing cards in the bar when the chaos began, pulled it open in hopes of heading upstairs. Only then did the full scale of the unfolding tragedy become painfully apparent.

“The stairway was full,” Dominic testified a week later at the coroner’s inquest. “I tried to pull a few out myself but could not. The kids were all hollering.” With no way to remove the children until more help arrived, he tried to offer what little comfort he could. The victims called out for water, and Dominic hastened to fill pails for them. Perhaps trying to give Maria company–or to shield her somewhat from what would be an evening of inconceivable horror–he returned to the kitchen and escorted her and their son to the next-door neighbor. The rest of the night, Dominic gave away liberal servings of beer and liquor to “the firemen that were helping upstairs, to fix them up.” If anyone tried to offer payment, he refused it. What good was a quarter or a dime in the face of this?

Dominic, Mary, and their son were fortunate, unlike many Calumet families who went home from that Christmas party bowed with grief. The disaster may have left its mark, however, as the Vairos did not remain long in the Italian Hall saloon and apartment. By 1916, they had moved to 400 Sixth Street. Mary tended to their son and his younger sister Marie, while Dominic went into business with a different partner, Charles Hoffman. Unfortunately for Hoffman and Vairo, Michigan voters passed a constitutional amendment in November 1916 banning liquor. Officially, Vairo’s bar became a “temperance saloon.” In reality, Dominic continued to sell harder drinks under the table, running afoul of the law in 1925. He and Mary also operated a boardinghouse before returning to the saloon business after Prohibition was repealed.

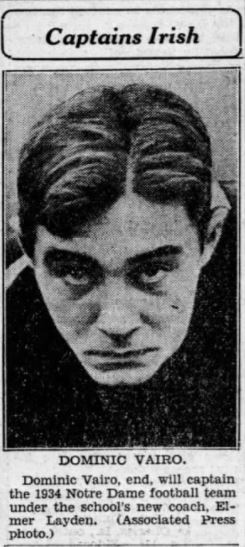

Meanwhile, the youngest Dominic–the newborn above whose head the Italian Hall disaster had unfolded–grew to be a thriving, sporty Calumet boy. Although he competed successfully in high school track and basketball, with an undefeated record for his junior team, football proved his greatest athletic passion. As captain of the Calumet High School football Copper Kings, he was named to the All-Upper Peninsula squad, and his skill drew the attention of collegiate teams. Ever since several Copper Country men, including George Gipp, had journeyed south to Notre Dame a decade earlier, a special relationship had existed between the Copper Kings and the Fighting Irish. Dominic became one of them and suited up for his first Notre Dame game in 1931.

He established himself on the team quickly. Playing left end, Dominic was a starter by the 1932 season. Exceptionally gifted both offensively and defensively, he had a knack for making pivotal plays that changed the course of the game. In a match against the storied Army team, for example, he caught a ball thrown from 30 yards away and ran for the winning touchdown. In December 1933, he was elected captain of the Irish for the 1934 season, his senior one, and helped to pull the team to another winning record. Notre Dame bestowed on him that year an honor he cherished for the rest of his life: the Byron V. Kanaley Award, given to senior student athletes judged to be the most outstanding as sportsmen and individuals.

In 1935, Dominic joined the Green Bay Packers, a favorite team of Yoopers. His stint turned out to be a brief one. A player from the South, Don Hutson, also came to the Packers as an end. Hutson’s skills amazed Dominic, who later said, “I pretty much forgot about pro football after I saw him play.” Although he would eventually play one more time for the now-defunct Chicago Gunners, Dominic turned his attention to other aspects of his life. After he received his business degree from Notre Dame, he took a job first with Ford, then with a Chicago printing press. There were romantic matters at hand, too: on May 16, 1936, he and Dorothy Jane Ahrbeck were married at a Notre Dame chapel. They would eventually welcome two children.

In an echo of thirty years earlier, Dominic returned to Calumet in 1939. His father had died on October 3 of coronary thrombosis, and once again it fell to a son to take over the family business. Although he did not remain a restauranteur for long, the move reestablished Dominic’s Copper Country roots and created new ones for Dorothy. Dominic served as a county clerk–with his term interrupted by military service during World War II–and operated an insurance agency, as well as participating in countless civic, religious, professional, and charitable organizations.

When the third Dominic Vairo to leave his mark on Calumet died on July 31, 2002, it was after a life whose early days were shadowed by tragedy and whose youth was marked by accomplishment. The family downstairs of the Italian Hall had many stories to tell.

An amazingly well researched and written story! I a YOOPER never heard of him but that is not a shock as I had cars on my mind. Good flashback ,I enjoyed it very much!