Part 2 of 2. Visitors who have not read “He Was Someone” should do so first.

October 4, 1959.

A woman picked wildflowers near a culvert on Davis Road in Mequon, Wisconsin. Weather data from General Mitchell Field, an airport thirty miles south, speaks to a pleasant day: temperatures reaching the upper 50s, precipitation holding off in the morning, a light breeze. No doubt the woman expected nothing more than to quietly gather some autumn flowers along the country road. It should have been an ordinary Sunday.

Instead, she became the first witness to a brutal crime–the first, other than the perpetrators, to see that Chester Breiney, alias Markku Jutila, was dead.

Reports of the woman’s ghastly discovery under the culvert quickly spread through Wisconsin and the nation, with all the confusion that accompanies the first days of an investigation. The child’s remains had suffered grievous indignities during their exposure to the elements, making it difficult for police and medical examiners summoned to the scene to assess the victim accurately. The head, with short blonde hair, appeared to belong to a girl between the ages of six and eight. In the first twenty-four hours of their investigation, police located the child’s leg bones, arm bones, and a portion of “her” torso. Half a mile north lay a partially-burned cardboard box that appeared, at first, to contain pieces of skin and bone, as well as a burlap bag, work pants, and a May 1959 Milwaukee newspaper. Rain and darkness put an early end to the first day’s search. Over the week that followed, however, investigators sifting through the topsoil under the culvert uncovered nearly the entirety of the child’s skeleton. They took the body to the Wisconsin State Crime Laboratory in Madison for further analysis. “There is no doubt,” said Mequon police chief Robert Milke, “but that she [sic] was murdered.”

Police pursued early leads that led them in a logical but incorrect direction. A neighbor said that he had seen a child’s limp hand hanging out of a car parked near the culvert in May. He reported the incident to police, but the car left before authorities arrived. His story, and the May 1959 newspaper, were ultimately red herrings, but only time would make that clear. Ozaukee County coroner Dr. James Walsh examined the body the first day and concluded that the victim had been out in the open for two to four months. He or a colleague later expanded that range to six months, still short of the actual time. State Crime Laboratory director Charles Wilson likewise corrected the first reports about the child’s sex: even his lab could not say whether the body, in its poor condition, was a boy or a girl.

Discovery of the child’s body predated anything like a nationwide index of missing persons, and no one–aside from his adoptive parents–yet had any reason to believe that a boy from Houghton County had been abandoned, dead, in Mequon. Police considered their local cases, relying on the first impressions that the victim was a girl. A six-year-old named Nancy Marie Ritchie had disappeared from Milwaukee with her mother in May. When Director Wilson reported evidence of multiple healed fractures in the body at his lab, Chief Milke pleaded for physicians who might have treated Nancy for injuries like that to contact him. Perhaps they had maintained X-rays that police could scrutinize. None materialized. Nancy’s father soon visited the state crime lab with a lock of his daughter’s hair but was unable to identify the body as hers. She would eventually be found alive. Meanwhile, a woman in Cincinnati contacted her local police department to suggest that her missing granddaughter Phyllis Jean Finney, also six, could be the unknown victim. This, too, came to nothing. The child’s body remained unclaimed and unnamed in Madison for decades, assigned the laboratory identification number 6426.

In Chicago, William and Hilja Jutila might have read the news from Wisconsin, might have heard about the body found in Mequon and felt a surge of panic. As days passed, then weeks, they may have relaxed, believing that they had once again escaped. But the first wheels had turned toward their arrest and to Chester’s identification, though no one knew it yet.

March 26, 1966.

Chicago. Houghton County Deputy A. Frans Heideman was certain that the Jutilas were hiding something.

If William and Hilja assumed that all four policemen in their home were from Chicago, speaking Finnish to each other as they attempted to coordinate stories about their son’s absence was a logical decision. If they knew that Heideman had come from the Upper Peninsula, however, what made them think Finnish would keep their secret? Back in the Copper Country, they had been surrounded by Finns, including a large cadre of immigrants, like Hilja, and a bevy of first-generation Americans, like William, who spoke Finnish before they learned English. They should have known. And now Deputy Heideman knew that William’s brothers’ suspicions, the ones that had prompted his journey to Chicago, were well founded.

Heideman alerted his Chicago counterparts to the Jutilas’ deception. The policemen herded the Jutilas into a car and drove to their Brighton Park precinct headquarters. There, they separated William and Hilja for independent questioning. Unsurprisingly, discrepancies in their stories emerged almost immediately, but the police pressed on. At length, according to the Chicago Tribune, Sergeant William Gorman approached William to say that the couple’s explanations couldn’t be reconciled. William finally broke. Markku was gone, he admitted. Hilja had beaten him to death.

Gorman went next to Hilja. “Your husband,” the Tribune quoted him as saying, “has made his peace with God” by confessing to their son’s murder. Hilja wept. Then, per the Tribune:

“He’s dead. We put him in a culvert.”

Police lit up the phone lines to Wisconsin cities, checking the route the Jutilas had taken south from Hancock. One of their calls yielded the revelation they sought: the unknown blonde child found under the Mequon culvert in 1959. Both the body and its location matched Markku too well to be coincidental. The case now had probable physical evidence and two admissions of guilt. It was time to seek justice.

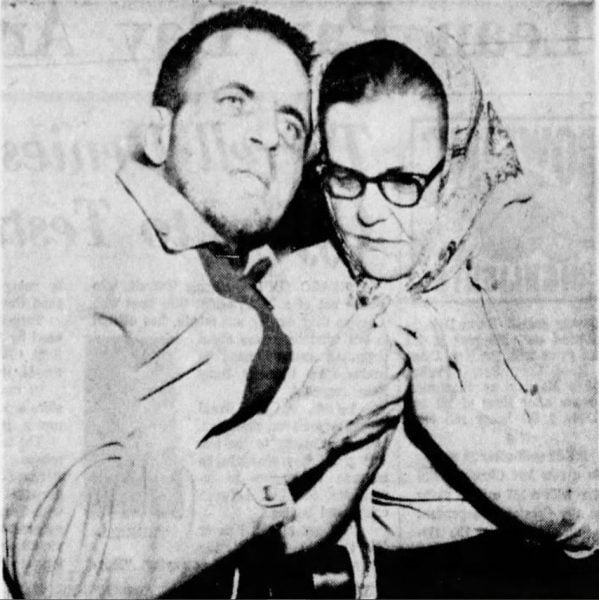

Perhaps the inauspicious beginning to the process should have been a sign that this justice would be elusive. The Jutilas appeared in Cook County Circuit Court on March 28, two days after their arrest. Judge Daniel J. Ryan, presiding over the arraignment, noted that the police had not submitted a formal complaint with the court file–a technicality that required him to release the couple. The police department quickly corrected their mistake and re-arrested the Jutilas. In court, the couple volunteered to be extradited to Michigan, but Hilja recanted any implication of her culpability. “I am innocent,” she said in an Associated Press report, “and I want to prove my innocence.” Deputy Heideman, who spent some time in Wisconsin looking over the Mequon case, retrieved William and Hilja and took them back to Michigan.

The Jutilas made their first appearance before Houghton County Justice of the Peace Louis Gerbec on April 1, 1966. The charges filed in the circuit court just days before were unsurprisingly grim: “William Russell Jutila… Hilja Maria Juttila [sic] feloniously, wilfully [sic], and of his (her) malice aforethought, did kill and murder one Markku Edward Michael Jutila.” No bond would be offered. The two pleaded not guilty. Both received attorneys appointed at court expense: twenty-five-year-old Gerald Vairo, whose saloonkeeper grandfather had been a first responder at the Italian Hall disaster, for Hilda and middle-aged newlywed Donald MacQueen, son of a C&H physician, for William. Through their lawyers, the Jutilas repeatedly and unsuccessfully petitioned for bail over the next three months.

Ivan LeCoro, a physician on staff at Houghton’s Rice Memorial Clinic for mental health, visited William in jail on May 11 and Hilja a week later to conduct psychiatric evaluations. Dr. LeCoro concluded that the Jutilas displayed normal intelligence and confidence; they showed no signs of legal insanity or mental illness. Hilja, he said, spoke cheerfully about her adoptive son until describing his death, when she cried. William insisted that he and his wife had “loved [Markku] very much.” Both remained firm in their assertions that they had not murdered their son but that he had died suddenly from an illness he picked up at kindergarten. They had not wanted to be blamed for failing to call a physician, said Hilja; they had not had the money for a doctor or an undertaker, claimed William. They had panicked; they had instantly decided to go to Chicago; they had fled with their child’s body and then abandoned him under the culvert. They were guilty of no more than that.

Presumably, inquiries about why the boy they claimed to love bore marks of physical abuse, medical neglect, and nutritional deficiency would be left for prosecutors when the case went to trial. But it never made it that far.

In September, preliminary examinations began in the Jutila case, with Justice Gerbec presiding. As in all such proceedings, the prosecution had to show that sufficient evidence suggested that the Jutilas had committed a crime. If the evidence fell short of demonstrating that said crime was, in fact, first degree murder, they could be charged with a lesser offense: murder in the second degree, manslaughter, even improper disposal of a body. Attorneys Vairo and MacQueen were permitted to cross-examine the prosecution’s witnesses at this hearing; it was atypical for the defense to call their own.

According to reports in the Daily Mining Gazette, prosecutor Walter T. Dartland summoned the three Chicago police officers to Houghton, along with William Laughlin, a University of Wisconsin anthropologist who had worked on the Mequon case. Dr. Laughlin described the body he had investigated and testified that it was consistent with a six-year-old boy like Markku Jutila. To quote the euphemistic Gazette, Laughlin also incorporated into his testimony references to “certain physical abnormalities or conditions” that the child’s skeleton exhibited–possibly signs of abuse he had endured. A former policeman from Mequon displayed photographs of the remains and spoke of their discovery in 1959. Friends and neighbors of the Jutilas were likewise called to testify, as were Houghton County police officers.

On the third day, Sheriff John Wiitanen brought to court the long tape recording of an interrogation the couple had undergone soon after being extradited to the Copper Country. At the defense’s request, Justice Gerbec cleared the courtroom gallery of spectators before playing the audiotape in its entirety. When it concluded, he adjourned the hearing, stating that he needed time to review its transcript and consider what charges were appropriate to bring against the Jutilas in Houghton County’s circuit court. Murder in the first degree was, after all, the most grievous criminal accusation that a person could face. If Gerbec could not cite reasons from the evidence presented that William and Hilja had committed this crime as defined under Michigan statutes, he could not permit the case to proceed with first-degree charges. He had to reduce them–or dismiss the case entirely.

The preliminary examination adjourned on September 22. It did not reconvene until November 10. In the meantime, attorneys Vairo and MacQueen met with Prosecutor Dartland, as they had done occasionally throughout the summer. Dartland had conceded to the Gazette in September willingness to reduce the charges, if the facts of the case as he presented them could not measure up to murder in the first degree. His discussion with Vairo and MacQueen on November 2 was one of the longest such conversations among the three, and Dartland might have concluded at this time that he could hope for no better than manslaughter. When the hearing began anew, he moved that the Jutila case proceed to the circuit court for trial on these grounds. The defense petitioned for an outright dismissal.

Justice Gerbec must have agonized over the thorny question of William and Hilja’s culpability in the weeks leading up to November 10. Had the prosecution made a sufficiently persuasive case? Dartland’s side needed to demonstrate that Markku Jutila was dead before anything else. The child’s body under the Mequon culvert seemed too similar to Markku’s and too aligned with the stories the elder Jutilas had offered to be coincidental. Yet the best of medical science in 1966 could not establish definitively that the decomposed remains were, in fact, his. In the absence of evidence that Markku was certainly deceased and what he deemed a persuasive connection to the Jutilas specifically–something on which Dartland’s arguments had hinged–Gerbec finally concluded that the prosecution’s case was inadequate. He granted the defense’s motion to dismiss.

William and Hilja Jutila walked free.

Disliking Chicago, they returned to Franklin Township and made it their home once again. Hilja died in Hancock on January 20, 1988; William passed away just months later, on April 23. Another 36 years would elapse before the boy they claimed to love could rest in peace.

The Jutila trial slipped away into obscurity. Markku’s biological mother, Josephine–who had named him Chester–died in 2001 in Marinette, Wisconsin. Few remained to remember that she had had a son; few remembered that he had died at the hands of someone else under darkly tragic circumstances. Surely she never forgot.

In October 2023, Wisconsin scholars and law enforcement officers assigned to cold cases reconsidered Mequon. Full details surrounding the early days of the new investigation, the analysis of the child’s remains and their signs of abuse, and the parties involved in the case can be found in the press release that doubles as Chester’s obituary. In brief, building on the initial physical re-assessment, the team decided to move forward with investigative genetic genealogy, a process of comparing a victim’s DNA profile (or, on occasion, a perpetrator’s) with those made publicly available by consumers who had decided to have their own genetics tested. Genealogical specialists then use archival records to sketch in the family tree between the victim and his/her matches. Although investigative applications of genetic genealogy are not without controversy, their power in several prominent cases is difficult to deny: the Golden State Killer, for example, finally faced justice after law enforcement and genealogists deployed the technique to pinpoint him.

Since the remains already had a possible identification, thanks to the Jutila trial, investigators sought to gather as much context for Chester/Markku as possible. The Michigan Tech Archives houses microfilmed copies of the Daily Mining Gazette, which documented many of the events of 1966; the original psychiatric evaluations of both William and Hilja and their court files are part of our State Archives collections. Sadly, since the case was dismissed before proceeding to the circuit court, the transcripts of the preliminary examination that Justice Gerbec pored over appear to have been lost to history. Nevertheless, the files and the Gazette articles provided meaningful details about the 1966 investigation as its 2024 counterpart pushed forward.

In September of this year, the DNA profile created from samples taken from the child’s body yielded hits for Josephine Breiney’s relatives in a public database. After reconstructing the genealogical connections between them, the team concluded that the Mequon remains belonged to Chester Breiney, son of Josephine, victim of William and Hilja. News of the resolved cold case broke in October.

Had genetic genealogy like this been available in 1966, the Jutilas might have been convicted.

On November 15, 2024, the little boy who suffered so much in life and languished so long in death was finally laid to rest in a donated plot in Port Washington, Ozaukee County, Wisconsin, following a funeral Mass at St. Peter of Alcantara parish. For sixty-five years, no one had called him by his name. Now he received it again, forever.

He was someone. He was Chester.