Biomedical Engineering

Made of fibrous connective tissue, tendons attach muscles to bones in the body, transferring force when muscles contract. But tendons are especially prone to tearing. Achilles tendinitis, one of the most common and painful sports injuries, can take months to heal, and injury often recurs.

Michigan Tech researcher Rupak Rajachar is developing a minimally-invasive, injectable hydrogel that can greatly reduce the time it takes for tendon fibers to heal, and heal well.

“To cells in the body, a wound must seem as if a bomb has gone off,” says Rajachar. His novel hydrogel formulation allows tendon tissue to recover organization by restoring the initial cues cells need in order to function. “No wound can go from injured to healed overnight,” he adds. “There is a process.”

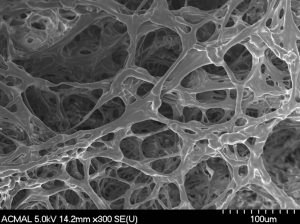

Rajachar and his research team seek to better understand that process, looking at both normal and injured tissue to study cell behavior, both in vitro and in vivo with mouse models. The hydrogel they have created combines the synthetic—polyethylene glycol (PEG), and the natural—fibrinogen.

“Cells recognize and like to attach to fibrinogen,” Rajachar explains. “It’s part of the natural wound healing process. It breaks down into products known to calm inflammation in a wound, as well as products that are known to promote new vessel formation. When it comes to healing, routine is better; the familiar is better.”

“To cells in the body, a wound must seem as if a bomb has gone off.”

The team’s base hydrogel has the capacity to be a therapeutic carrier, too. One formulation delivers low levels of nitric oxide (NO) to cells, a substance that improves wound healing, particularly in tendons. Rajachar combines NO and other active molecules and cells with the hydrogel, testing numerous formulations. “We add them, then image the gel to see if cells are thriving. The process takes place at room temperature, mixed on a lab bench.”

Two commonly prescribed, simple therapies—range of motion exercises that provide mechanical stimulation, and local application of cold/heat—activate NO in the hydrogel, boosting its effectiveness.

“Even a single injection of the PEG-fibrinogen-NO hydrogel could accelerate healing in tendon fibers,” says Rajachar. “ Tendon tissues have a simple healing process that’s easier to access with biomaterials,” he adds. Healing skin, bone, heart, and neural tissue is far more complex. Next up: Rajachar plans to test variations of his hydrogel on skin wounds.