Joe Foster shares his knowledge on Husky Bites, a free, interactive webinar this Monday, July 13 at 6 pm EST. Learn something new in just 20 minutes, with time after for Q&A! Get the full scoop and register at mtu.edu/huskybites.

What if you had a high-tech job, but spent your work day outside, enjoying nature and fresh air each day? If you like computing, and the great outdoors, you need to learn more about what it takes to become a geospatial engineer.

Joe Foster is a professor of practice in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Michigan Tech. He teaches courses in the elements of land surveying. He has served as a Principal for successful Land Surveying companies in both Minnesota and Michigan, directing and overseeing a wide range of projects. “I’m also an old Michigan Tech alum, with a Bachelor’s degree in Forestry, and a second Bachelor’s degree in Surveying, both from Michigan Tech,” he notes.

Studying geospatial engineering is both an adventure and a learning experience, says Foster. A lot of learning—and geospatial wizardry—takes place outdoors, in the field.

“Surveyors are experts at measuring,” Foster explains. “A myriad of equipment have been used over the years to accomplish the task, tools of the trade, so to speak. Over time, Surveying has evolved to become more, known now as Geospatial Engineering.”

Surveyors, now known as Geospatial Engineers, measure the physical features of the Earth with great precision and accuracy, calculating the position, elevation, and property lines of parcels of land. They verify and establish land boundaries and are key players in the design and layout of infrastructure, including roads, bridges, cell phone towers, pipelines, and wind farms.

And they are in demand. “There is an ongoing need for Surveyors,” says Foster. “Jobs are open and can’t be filled fast enough. We have a great need for those with an interest and aptitude for the profession.”

All land-based engineering projects begin with surveying to locate structures on the ground,” says Foster. Numerous industries rely on the geospatial data and products that geospatial engineers provide. With advances in technology, the need is increasing, too—from architectural firms, engineering firms, government agencies, real estate agencies, mining companies and others.

Out in the field, Geospatial Engineers peer “through the looking glass” using numerous tools. “Robotic total stations, GPS receivers, scanners, LiDAR, and UAVs only scratch the surface of what is available in the toolbox,” says Foster.

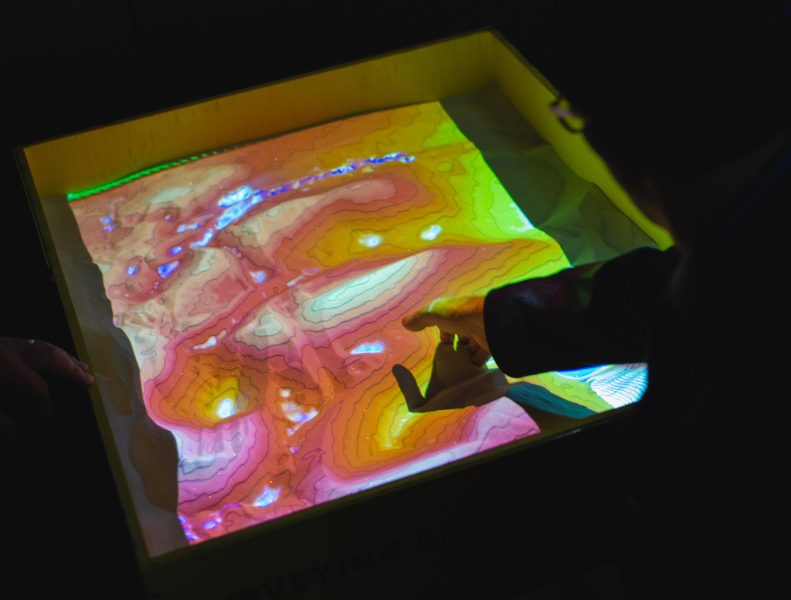

Advances in GPS technology have led to the use of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) for mapping, as well as geospatial data capture and visualization technologies. Geospatial engineers also use virtual reality integration, Structure from Motion (a technique which utilizes a series of 2-dimensional images to reconstruct the 3-dimensional structure of a scene or object, similar to LiDAR), and unmanned aerial vehicle systems (drones). At Michigan Tech, students learn to use these tools, too.

Geospatial engineering students choose from two concentrations, says Foster. “Professional Surveying prepares students to become state-licensed professional surveyors. Students learn to locate accurate real property boundaries, conduct data capture of the natural/man-made objects on the Earth’s surface—and conduct digital mapping for use in design or planning.”

The second concentration is Geoinformatics. “Students learn to manage large volumes of digital geo-information that can be stored, manipulated, visualized, analyzed, and shared,” he adds. “Students use more Geographic Information Science (GIS) tools, remote sensing, big data acquisition, and cloud computing.”

Once you’re working as a geospatial engineer, you could end up using both concentrations. “Land surveying and geographic information systems (GIS) are complementary tools,” he says.

Foster is excited about the growth of opportunities in the profession. During his own career, Foster worked as a principal for successful land surveying companies in both Minnesota and Michigan, directing and overseeing a wide range of projects, including boundary, county remonumentation, and cadastral (USDA-FS) retracement surveys; topographic, site planning, and flood plain surveys; mine surveys (surface and underground); plats and subdivisions; and both conventional and GPS control surveys. He’s managed contracts with the USDA-Forest Service, mining companies in Northern Minnesota, the State of Michigan, and more.

Foster is also a member of the Michigan Society of Professional Surveyors (MSPS). At Michigan Tech, he’s advisor to the Douglass Houghton Student Chapter of the National Society of Professional Surveyors (DHSC). Last year the group continued their tradition with the annual General Land Office (GLO) Workshop. Sponsored by DHSC and conducted by Pat Leemon, PS, retired U.S. Forest Surveyor from the Ottawa National Forest, it is a search/perpetuation of an original GLO corner. “That’s a once in a lifetime experience for a Surveyor,” says Foster.

When did you first get into surveying? What sparked your interest?

I first got interested in Surveying while studying forestry at Michigan Tech. Surveying was one of the courses in the program. That’s where I learned there could be an entire profession centered on surveying alone. I was hooked. It incorporated everything I had come to enjoy about forestry; working outside, using sophisticated equipment, drafting, and actually putting all the math I had learned to practical use. After earning my first bachelor’s degree in Forestry, I decided to get a second bachelor’s degree in Surveying and to pursue that as my career.

Tell us about your growing up. What do you do for fun?

I was born and raised in Michigan and have worked in the forest product industry and surveying profession for over 25 years. Work has taken me to just about every corner of Northern Minnesota and Michigan’s Copper Country. I came to know my wife, Kate at Fall Camp at Alberta, at Michigan Tech’s Ford Forestry Center. We made our home in the Keweenaw, where we both have strong family ties.

Lake Superior is our first love, and one that we share. Here’s a little known fact….Keweenaw County has the highest proportion of water area to total area in the entire United States, with 541 square miles of land and 5,425 square miles of water. Nearly 90 percent of Keweenaw County is under the surface of Lake Superior!