Erik Herbert and Iver Anderson generously shared their knowledge on Husky Bites, a free, interactive Zoom webinar hosted by Dean Janet Callahan. Here’s the link to watch a recording of his session on YouTube. Get the full scoop, including a listing of all the (60+) sessions at mtu.edu/huskybites.

Tonight’s Husky Bites delves directly into our phones, laptops and tablets, on how to make them cleaner, safer, faster, and more environmentally friendly. It’s about materials, and how engineers focus on understanding, improving inventing materials to solve big problems.

Materials Science and Engineering Assistant Prof. Erik Herbert is focused on the lithium metal inside the batteries that power our devices. Lithium is an extremely reactive metal, which makes it prone to misbehavior. But it is also very good at storing energy.

“We want our devices to charge as quickly as possible, and so battery manufacturers face twin pressures: Make batteries that charge very quickly, passing a charge between the cathode and anode as fast as possible, and make the batteries reliable despite being charged repeatedly,” he says.

On campus at Michigan Tech, Dr. Herbert and his research team explore how lithium reacts to pressure by drilling down into lithium’s smallest and arguably most befuddling attributes. Using a diamond-tipped probe, they deform thin film lithium samples under the microscope to study the behavior on the nanoscale.

“Lithium doesn’t behave as expected during battery operation,” says Herbert. Mounting pressure occurs during the charging and discharging of a battery, resulting in microscopic fingers of lithium called dendrites. These dendrites fill pre-existing microscopic flaws—grooves, pores and scratches—at the interface between the lithium anode and the solid electrolyte separator.

During continued cycling, these dendrites can force their way into, and eventually through, the solid electrolyte layer that physically separates the anode and cathode. Once a dendrite reaches the cathode, the device short circuits and fails, sometimes catastrophically, with heat, fire and explosions.

Improving our understanding of this fundamental issue will directly enable the development of a stable interface that promotes safe, long-term and high-rate cycling performance.

“Everybody is just looking at the energy storage components of the battery,” says Herbert. “Very few research groups are interested in understanding the mechanical elements. But low and behold, we’re discovering that the mechanical properties of lithium itself may be the key piece of the puzzle.”

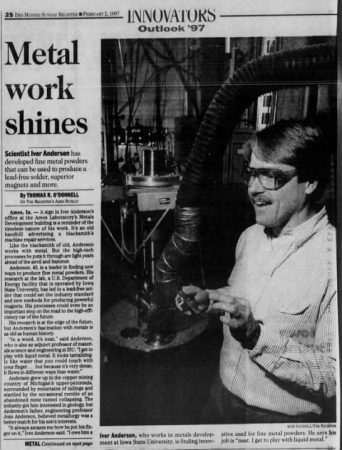

Iver Anderson, PhD will be Dean Callahan’s co-host during the session. Dr. Anderson is a Michigan Tech alum and senior metallurgical engineer at Ames Lab, a US Department of Energy National Lab. A few years ago, he was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame, for inventing a successful lead-free solder alloy, a revolutionary alternative to traditional tin/lead solder used for joining less fusible metals such as electric wires or other metal parts, and in circuit boards.

As a result, nearly 20,000 tons of lead are no longer released into the environment worldwide. Low-wage recyclers in third-world countries are no longer exposed to large concentrations of this toxic material, and much less lead leaches from landfills into drinking water supplies.

“There is no safe lead level,” says Anderson. “Science exists to solve problems, but I believe the questions have to be relevant. The motivation is especially strong to solve a problem when somebody says it is not possible to solve it,” he adds. “It makes me feel warm inside to have solved one problem that will help us going on into the future.”

Anderson earned his BS in Metallurgical Engineering in 1975 from Michigan Tech. “It laid the foundation of my network of classmates and professors, which I have continued to expand,” he said.

Anderson went on to earn his MS and PhD in Metallurgical Engineering from University of Wisconsin-Madison. After completing his studies in 1982, he joined the Metallurgy Branch of the US Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, DC.

With a desire to return to the Midwest, he took a position at Ames Lab in 1987 and has spent the balance of his research career there and at Iowa State.

“I hope our work has a significant impact on the direction people take trying to develop next-gen storage devices.”

Professor Herbert, when did you first get into engineering? What sparked your interest?

The factors that got me interesting engineering revolved around my hobbies. First it was through BMX bikes and the changes I noticed in riding frames made from aluminum rather than steel. Next it was rock climbing, and realizing that the hardware had to be tailor made and selected to accommodate the type of rock or the type or feature within the rock. Here’s a few examples: Brass is the optimal choice for crack systems with small quartz crystals. Steel is the better choice for smoothly tapered constrictions. Steel pins need sufficient ductility to take on the physical shape of a seam or crack. Aluminum cam lobes need to be sufficiently soft to “bite” the rock, but robust enough to survive repeated impact loads. Then of course there is the rope—what an interesting marvel—the rope has to be capable of dissipating the energy of a fall so the shock isn’t transferred to the climber. Clearly, there is a lot of interesting materials science and engineering going on here.

Hometown, hobbies?

I am originally from Boston, but was raised primarily in East Tennessee. Since 2015, my wife Martha and I have lived in Houghton with our three youngest children. Since then, all but one have taken off on their own. When I’m not working, we enjoy visiting family, riding mountain bikes, learning to snowboard, and watching a good movie.

Dr. Anderson, when did you first get into engineering? What sparked your interest?

I grew up in Hancock, Michigan, in the Upper Peninsula. Right out my back door was a 40 acre wood that all the kids played in. The world is a beautiful place, especially nature. That was the kind of impression I grew up with. My father was observant and very particular, for instance, about furniture and cabinetry. He taught me how to look for quality, the mark of a craftsman, how to sense a thousandth of an inch. I carry that with me today.