David Shonnard and Felix Adom generously shared their knowledge on Husky Bites, a free, interactive Zoom webinar hosted by Dean Janet Callahan. Here’s the link to watch a recording of his session on YouTube. Get the full scoop, including a listing of all the (60+) sessions at mtu.edu/huskybites.

What are you doing for supper this Monday night 11/9 at 6 ET? Grab a bite with Dean Janet Callahan and Chemical Engineering Professor David Shonnard, longtime director and founder of Michigan Tech’s Sustainable Futures Institute. Last week he won Michigan Tech’s 2020 Research Award.

During Husky Bites, Shonnard promises to shed some light and some hope on waste plastics—the role they play in our society and economy and their harm to the environment, especially the oceans and its biodiversity.

He’ll also take us on a walk down a remote Lake Superior beach to hunt for waste plastics, show us what he and his students found, where they found it, and what that means.

Felix Adom, one of Prof. Shonnard’s graduate students will join in, too. Dr. Adom grew up in Ghana, attending Kwame Nkrumah’ University of Science and Technology in Kumasi for his bachelor’s degree in chemistry. He earned his PhD in Chemical Engineering at Michigan Tech in 2012, and then worked as a post-doc researcher and energy analyst at Argonne National Lab. He then joined Shell as greenhouse gas intensity assessment technologist, and is now carbon strategy analyst at Shell.

Shonnard founded and is fully devoted to Michigan Tech’s Sustainable Futures Institute, which brings together undergraduate students, graduate students, scientists and engineers from multiple disciplines in research and education projects. SFI members—more than 100 on campus—address technical, economic, and social issues related to the sustainable use of the Earth’s limited resources.

During his time at Michigan Tech, Adom was a member of SFI. On one project, he worked with a team of students in Shonnard’s hydrolysis lab to analyze a waste product of the wet mill corn ethanol industry—a thick, caramel-colored syrup. Ethanol production from corn creates an abundance of corn byproducts—seven pounds for every one gallon of ethanol according to some estimates. The syrup came by way of Working Bugs LLC, a green chemical manufacturer based in East Lansing, Michigan. Adom and the team identified the chemical make-up of the syrup and helped determine its value as a possible feedstock. They also discovered ways to convert the syrup, a waste stream, into a sugar- and amino acid-rich fermentation medium for other biofuels.

Today Adom is based in Richmond, Texas, not far from Houston. He is a carbon strategy analyst for Shell. “When I joined this team in 2016, it was a small group of 5 people. Today our team has 40 people and it is heavily funded.”

“Ever since Felix graduated, I have proudly watched from a distance the terrific trajectory of his career,” says Shonnard. He’s now helping a major oil company to develop their strategies to be more sustainable. I am really happy to see that.”

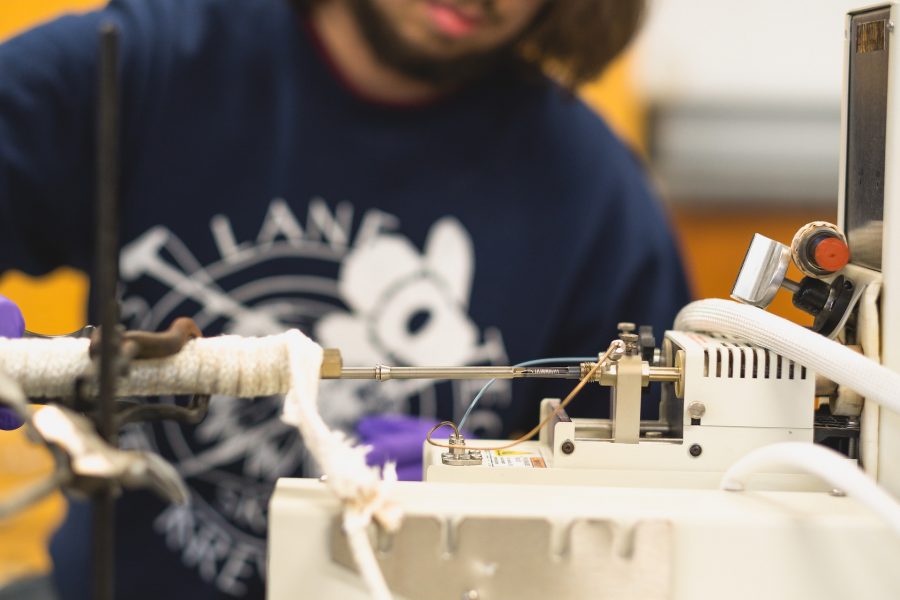

The beach study, performed by chemical engineering undergraduates Mahlon Bare and Jacob Zuhlke, focused on identifying and quantifying macroplastic particles discovered on a beach along Lake Superior on the Keweenaw Peninsula in Michigan within Gratiot River County Park. The park receives little foot traffic and is located in a remote part of the Peninsula. Searching five 100-foot sites spaced 1000 feet apart, the team gathered any visible surface plastic. They also processed sand dug from one-ft. deep holes. Researchers took samples of recovered plastic pieces and analyzed their composition using a micropyrolysis process and gas chromatography/ mass spectrometry (GC/MS) system. No microplastics were discovered in the sand.

“Technology enables a circular flow of recycling. Right now, waste plastics are a cost, but they could be of value if we can convert them back into other, reusable forms. If they have value, then they’re less likely to get thrown out.”

Prof. Shonnard, how did you become focused on sustainability as a chemical engineer?

“During my PhD at UC Davis, my advisor allowed me to take courses and conduct research outside of the traditional discipline of chemical engineering, so I could apply my skills to environmental problems. Once at Michigan Tech, our culture of collaboration across campus stimulated my research into areas of sustainable bioenergy and more recently into waste plastic recycling.”

What are the most important things all engineers should know about sustainability?

“Engineers, in my experience, often think a problem can be solved using the skills we possess. Unfortunately, this is not true when it comes to sustainability. Engineers need to collaborate outside their fields of expertise, with environmental scientists, economists, social scientists, and others to address these challenges.”

When did you first get into engineering? What sparked your interest?

As a young man searching for my career direction, among other things I restored old classic Porsche automobiles. This sparked my interest in engineering and to gain a deeper understanding about how the parts of the vehicle worked. My freshman year included chemistry, which I loved, and when combined with my interests in math I decided on chemical engineering, and have been super happy ever since.

Hometown, Hobbies, Family?

My wife, Gisela, is originally from Germany and before that Brazil, so international travel is in our DNA. With Gisela and my two children (now grown and into their careers), we traveled a lot to Germany and Europe more broadly to visit relatives. My only sabbatical was in Germany at a global chemical company headquartered in Ludwigshafen, Germany (can you guess the company?). My sustainability research included collaborations in Central and S. America (Mexico, Brazil, Argentina).