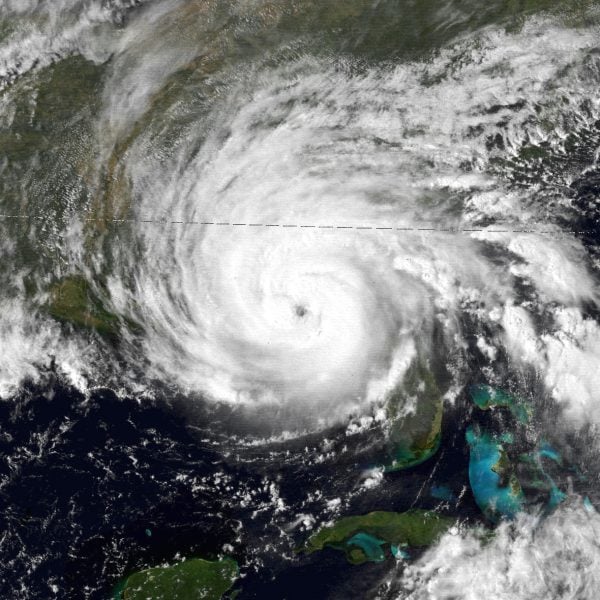

Credit: The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

In his guest blog, Michigan Tech mechanical engineering alumnus Patrick Parker ’75 tells the story of working in a power plant during Hurricane Fredric, a Category 4 with sustained winds of 155 mph. It happened just four years after Pat graduated from Michigan Tech.

“Teamwork is the fuel that allows common people to attain uncommon results.” — Andrew Carnegie

“Every Bad situation is a blues song waiting to happen” — Amy Winehouse

“In teamwork, silence isn’t golden, it’s deadly.” — Mark Sanborn

“Talent wins games, but teamwork and intelligence win championships.” —Michael Jordan

“Alone we can do so little, together we can do so much!” — Helen Keller

Early in my career, I was a maintenance supervisor at a 7-unit power station just north of Pensacola, Florida. I had a crew of 15 people—electricians, mechanics, and welder/mechanics. We maintained equipment throughout the plant, and made repairs when any operational issues arose, to help avoid a power outage on one or more of the units.

While living on the Gulf Coast, I had heard many stories of hurricane events, most of which involved the loss of property due to the high winds, tremendous rainfall (often over 20 inches) and if you were close to the beach, the storm surge could have waves over 10 feet washing ashore. I heard stories of lost friends and family, stories that usually ended with “I told them to “move up north till this is over!’”

In early September of 1979, we began watching closely a tropical storm off the southern tip of Florida moving North by NW, directly toward us. After a couple of days, its gusts were often much higher.

Our plant manager had lived through several events like this and began issuing instructions that would prepare us for the worst, while we prayed for the best. We began with a thorough clean up of the plant for anything important to be moved somewhere it would be safe. We paid special attention to any of our safety equipment, fire fighting gear, tools, rigging, and anything that could be useful in dealing with fire,collapse of structures, flooding, or any first aid. We also moved anything hazardous such as flammables, gases, or anything that could cause harm if it got out into the area around the plant. As that went forward, our Plant Manager made our staffing plans for the upcoming event.

Our operations department in the downtown office sent us instructions to put all seven of our units into service, to help ensure some redundancy in the event we start tripping units off line, due to storm damage. In order to do that we called in our operators who were skilled in the use of oil and natural gas for combustion. We finally worked it out, so all our operators were here (half were sleeping) as well as all our maintenance staff to address needs as they arose. We had also arranged for a good store of water, food, and sleeping arrangements for those workers who were staying overnight. All our employees all wanted to stay, but there were some with responsibilities that forced them to go home.

The coal yard would be another concern due to its size and proximity to a river that dumped into the Gulf. We received coal usually by barge which was less than 50 feet from the river. Our people who worked there began constructing a dike made of coal that would minimize any spillage into the river as strong winds and rain began. (Two years later they built a concrete dike about 2 feet thick by 8 feet tall around the portion of the coal pile adjacent to the river.)

As the storm approached, we began making final preparations for the high winds and rain by closing all doors and reinforcing them with steel beams/braces. The windows were covered with plywood and canvas sheets, and the smaller windows near walkways were covered with duct tape to minimize shattering and spreading glass.

Anything that was likely to get airborne during the wind and rain was moved off the site, such as contractor trailers, port-a-johns, and unnecessary equipment. The concern was to protect the transmission lines and support poles from being knocked down or shorted out. We did a thorough final walk around of all plant space, paying special attention to the area outside to check for anything else. Then the hard part began—WAITING!

We were on our feet almost nonstop, walking around, looking, checking and listening for anything that might indicate a problem. Many of us laid down somewhere and slept as we had been working almost 30 hours straight.

On September 12, 1979, in the early evening hours, Hurricane Fredric’s eye came ashore as a category 4 with sustained winds of 155 mph. It was located about half way between Pensacola Florida, and Mobile, Alabama. That landfall put us in the northeast quadrant of the storm, which typically is the worst part of the storm due to a hurricane’s counter clockwise rotation.

After 40 years I still have many images of what happened that week and the aftermath that followed for many weeks. I’ll share just a couple: I remember going to the top floor that was still inside the boiler structure with the Plant Manager (about 9 stories up) to look south toward Pensacola. I was expecting to see light coming from the city as usual, but there was none.

About every 3 to 5 minutes there was a large BOOM and a large flash of orange light coming from several miles south. I didn’t know what was happening, and it made me more than a little apprehensive. I imagined some industrial plant nearby exploding and burning. I asked the Manager what he thought it was, and he said, “Oh that’s just the pole mounted transformers blowing up. There will be a lot of overtime work for the Division Linemen to do when this is all over!” Was he ever right!

“There is a practice that still goes on today that couldn’t speak more clearly about the importance of working together. When the rain and wind subsided, hundreds of trucks from Line Departments of other power companies came from all over the southern states, converging on Pensacola and all the way to Mobile—bringing manpower, power poles, lights, transformers, and miles of conductor wire to assist with our repairs, all around the city and neighboring counties.”

The division manager for the area around Pensacola came to the Plant and asked if he could “borrow” some of our people, especially electricians to assist in the walk down of all the “radials” as everyone he had was busy with the repairs. Our plant manager gave him almost all our electricians, and a couple of our engineers to help.

When electric power leaves the power plant, it passes through a Generation Step-Up transformer (GSU) which raises the voltage to transmission power levels (typically 345 KVA). The transmission line then carries the power to a ‘substation’ which lowers the voltage to typically 25 KVA and then sends the power in different directions around the city/county on the wooden power poles commonly seen. Each separate circuit is called a “radial”.

The trouble is there are many hundreds of miles of radials, which are very vulnerable to storms due to the high winds, lightning and heavy rain. Plus, the radials will not call and tell where the damage is; you must go out looking for them! Someone must walk each radial from one end to the other, and radio the Lineman Dispatcher, informing them what damage was found, and where it is located. Then they can dispatch people, parts, and equipment to make the repairs, thus hoping to save a lot of time with more people out looking. It works very well.

At the plant we had only one significant event during the storm. The plant had been built 75 feet into the ground to minimize the stress on the structure during high winds. The ‘pump room’ (75 feet down) was cooled, thankfully, by several large fans (12 feet in diameter) that pulled air in from outside. The problem was that the duct work for the fan also provided a perfect route for rainwater to flow in. We had all seven units running, when one of our staff noticed one of the large 480 Volt busses was on fire. As things happen in life, one of the cooling fans was right over the buss. We found a perfect example why water and electricity don’t mix well, as it was spitting sparks, flashes, and fire from the top of the buss.

Some of our firefighting group stretched out a fire hose and charged it up. I learned an important lesson that night. It seems it is sometimes possible to put out an electric fire with water. Instead of spraying the buss directly with the stream of water (inviting electric shock), they aimed the fire hose steeply upward, bouncing the stream of water off the flooring of the deck above the buss. A heavy downpour descended on the buss which eventually put the fire out.

The other unfortunate detail lay right above the buss in a large cable tray which routed most of the control wiring for the plant substation. As it burned and shorted out, almost all the switch yard breakers opened (for safety sake, they default open), which tripped 6 of the 7 units. We managed to keep unit 6 running at 300 megawatts. I guess the “good news” for us was even if we had all the units running, the transmission lines and distribution system was out of service due to the storm. We had no way of sending our power anywhere. It took us about a week to rewire the substation controls, the 480-volt buss, and other damage that was surprisingly minimal. I give our plant manager the credit for that. We had no injuries during the event or in the time that followed.

I learned several very important lessons during that experience:

1. Prepare, Prepare, Prepare! I believe that was the key to minimizing damage and preventing any injury.

2. Contain any Hazardous Materials—if they get loose, it doesn’t end well!

3. When someone asks for help GIVE IT. Work Together. You will need help one day, so make friends when you can.

4. NEVER, NEVER spray water on an energized electric buss! It usually doesn’t end well! I think we were very, very lucky!

5. When a hurricane approaches, the smartest thing to do is evacuate, sooner than later!

Most residents feel that as soon as the power company has all their wiring ‘hot’ again, all they must do is close their house breaker to restore power. Actually, the power company will deliberately open the wiring at the top of each power pole going to homes or businesses to prevent people from electrocuting themselves, and/or setting their house on fire due to internal damage to their home as a result of the storm. Before the power company will rewire the pole for you, they must see an inspection report of your home or business from a licensed electrician to make sure it is okay to activate power. As you might imagine, this frustrates the owners, particularly business owners. But the risks outweigh a few extra days without air conditioning.

About the Author

Pat Parker grew up in Ferndale, Michigan and went on to graduate from Michigan Technological University in 1975 with a BS in Mechanical Engineering.

His mom was from London, England. She was 14 during the London ‘blitz’ of WWII. His dad, from west Tennessee, flew for the Army Air Force in B-17s as a recon photographer. His dad met his mom while on leave in London, by pretending he was lost!

Pat first grew interested in mechanical engineering with the influence of an elderly neighbor by the name of John Pavaleka, who came to the US in the early 1920s from Czechoslovakia. John graduated from Yale with an ME degree. After graduation, he went to work for Boeing Aircraft, designing hydraulic systems in the WWII bombers—all the hydraulic systems that operated the gun turrets, landing gear, and flight controls. John was incredibly talented, and had his own hand-carved collection of airplanes of numerous designs including one with forward-swept wings.

While at Michigan Tech, Pat did well in Heat Transfer, Fluid Mechanics, and Thermodynamics courses. A classmate, Rick Sliper, encouraged Pat to go into the power generation field. So after graduation, Pat went to work for a company that built large power-generation boilers—doing construction, commissioning, and ongoing maintenance. Beginning as a first line supervisor, Pat moved up to power plant manager at two locations.

Tired of all the travel (living largely in motels) and wanting to start a family, Pat changed jobs, in order to establish a home. Still, over 42 years, Pat and his family managed to live in six states.

Some of Pat’s work-related accomplishments include a great safety and environmental record; lowering operating costs; and improving availability. He also won an award from the State of Florida for helping two elementary schools with their education goals and their Christmas celebrations.

Reluctantly retiring for health issues, Pat now spends time woodworking, writing, camping—and spoiling his two granddaughters!