Simon Carn and Bill Rose generously shared their knowledge on Husky Bites, a free, interactive Zoom webinar hosted by Dean Janet Callahan. Here’s the link to watch a recording of his session on YouTube. Get the full scoop, including a listing of all the (60+) sessions at mtu.edu/huskybites.

What are you doing for supper this Monday night 2/15 at 6 ET? Grab a bite with Dean Janet Callahan and Volcanologist Simon Carn, Professor, Geological and Mining Engineering and Sciences (GMES).

Also joining in will be GMES Research Professor Bill Rose, one of the first in volcanology to embrace satellite data to study volcanic emissions and is a well-recognized leader in the field.

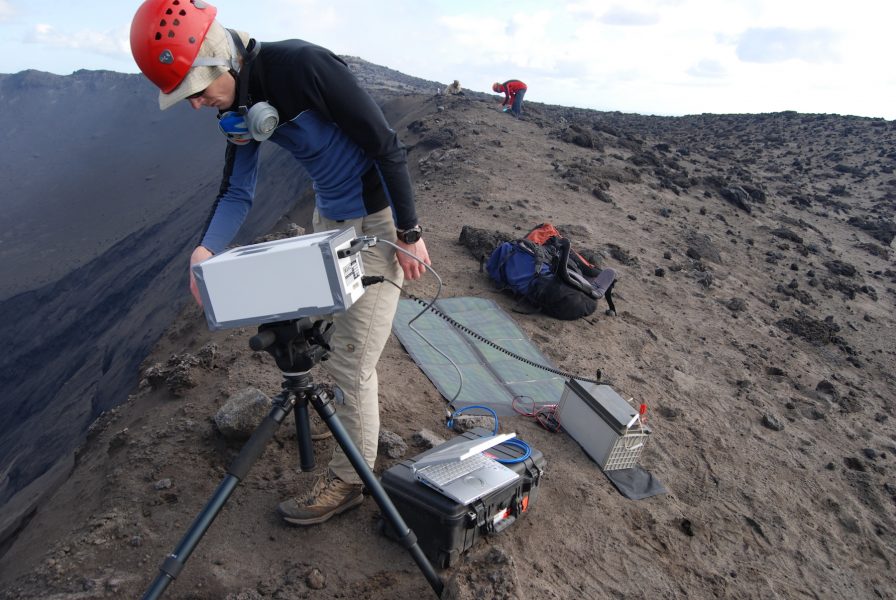

Prof. Carn studies carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide emissions from volcanoes, using remote sensing via satellite.

His goal: improved monitoring of volcanic eruptions, human health risks and climate processes—one volcanic breath at a time.

“Volcanology—the study of volcanoes—is a truly multidisciplinary endeavor that encompasses numerous fields including geology, physics, chemistry, material science and social science,” says Carn.

Carn applies remote sensing data to understand the environmental impacts of volcanic eruption clouds, volcanic degassing, and human created pollution, too.

“Sulfur dioxide, SO2, plays an important role in the atmosphere,” he says. “SO2 can cause negative climate forcing. It also impacts cloud microphysics.”

Many individual particles make up a cloud, so small they exist on the microscale. A cloud’s individual microstructure determines its behavior, whether it can produce rain or snow, for instance, or affect the Earth’s radiation balance.

“During Husky Bites I’ll discuss volcanic eruptions and their climate impacts, he says. “I’ll describe the satellite imagery techniques, and talk about the unique things we can measure from space.”

Carn was a leading scientist in an effort to apply sensors on NASA satellites, forming what is called the Afternoon Constellation or ‘A-Train’ to Earth observations. “The A-Train is a coordinated group of satellites in a polar orbit, crossing the equator within seconds to minutes of each other,” he explains. “This allows for near-simultaneous observations.”

The amount of geophysical data collected from space—and the ground—has increased exponentially over the past few years,” he says. “Our computational capacity to process the data and construct numerical models of volcanic processes has also increased. As a result, our understanding of the potential impacts of volcanoes has significantly advanced.”

That said, “Accurate prediction of volcanic eruptions is a significant challenge, and will remain so until we can increase the number of global volcanoes that are intensively monitored.”

Carn is the principal investigator on a project funded by NASA, “Tracking Volcanic Gases from Magma Reservoir to the Atmosphere: Identifying Precursors, and Optimizing Models and Satellite Observations for Future Major Eruptions.”

He is a member of the International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth’s Interior, and the American Geophysical Union. He served on a National Academy of Sciences Committee on Improving Understanding of Volcanic Eruptions.

Carn has taught, lectured and supervised students at Michigan Tech since 2008 and around the world since 1994 at the International Volcanological Field School in Russia, Cambridge University, the Philippines Institute of Volcanology and Seismology and at international workshops in France, Italy, Iceland, Indonesia, Singapore and Costa Rica.

“After finishing my PhD in the UK, I worked on the island of Montserrat (West Indies) for several months monitoring the active Soufriere Hills volcano. This got me interested in the use of remote sensing techniques for monitoring volcanic gas emissions. I then moved to the US for a postdoc at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, using satellite data to measure volcanic emissions.

While there, I started collaborating with the Michigan Tech volcanology group, including Dr. Bill Rose.”

Rose, a research professor in the Department of Geological and Mining Engineering and Sciences at Michigan Tech, was once the department chair, from 1991-98.

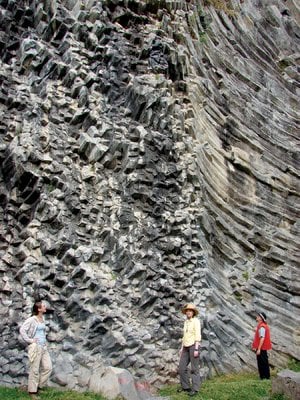

“Houghton, where Michigan Tech is located, is really an important place for copper in the world,” he says. There is a strong relationship between the copper mines here and volcanoes. We live on black rocks that go through the city and campus, some jutting up over the ground. Those rocks, basalt, are big lava flows, the result of a massive volcanic eruption, a giant Iceland-style event.”

“Arguably, Michigan Tech owes its beginning to volcanic activity, which is ultimately responsible for the area’s rich copper deposits and the development of mining in the Keweenaw,” he says.

“I was very much aware of the volcanic context when I arrived in Houghton as a young professor,” adds Rose. “I had a dual major in geography and geology, but the chance to work in an engineering department sounded good to me. It gave me a chance to go outside, working hands-on in the field.”

Rose did everything he could to get his students to places where they could be immersed in science. For many geology graduates, those trips were the highlight of their Michigan Tech education.

“I always took students with me on trips,” says Rose. “That was my priority. After all, the best geoscientists have seen the most rocks. We went all over the world, looking at volcanoes, doing research, and going to meetings,” he says. “I usually took more students with me than I had money for.”

Not all students could afford to travel, however. So when Bill (partially) retired in 2011, he decided to do something about that. “My dream was to create a quarter-million- dollar fund for student travel,” he says. He launched the Geoscience Student Travel Endowment Fund with a personal donation of $100,000.

In 2004 Rose started the Peace Corps Master’s International Program at Michigan Tech, now a graduate degree in Mitigation of Geological Natural Hazards, a program with strong connections with Central American countries and Indonesia. He also developed Keweenaw Geoheritage, in hopes of broadening geological knowledge of the region and of Earth science in general.

His work during his 50 years at Michigan Tech includes volcanic gas and ash emission studies, including potential aircraft hazards from volcanic clouds.

Prof. Rose, what accomplishment are you most proud of?

“My students. I treasure the time I have spent with them. I am laid back. I have been able to work with wonderful students every day of my 45 years at Michigan Tech, thousands of students. My style with these fine people is to give them hardly any orders. I encouraged them to follow their nose and network with each other.”

Professor Carn, when was the moment you knew volcanology was for you?

“The first active volcano I encountered was Arenal in Costa Rica during my travels after finishing high school. However, I think the point that I first seriously considered volcanology as a career was during my MS degree in Clermont-Ferrand, France. The first field trip was to Italy to see the spectacular active volcanoes Etna, Stromboli and Vesuvius.”

What do you like most about volcanology?

“Studying volcanoes is undeniably exciting and exotic. We are lucky to visit some spectacular locations for fieldwork and conferences. New eruptions can occur at any time, so there’s always something new and exciting to study. We are also fortunate in that it is relatively easy to justify studying volcanoes (e.g., to funding agencies), given their potentially significant impacts on climate, the environment and society.”

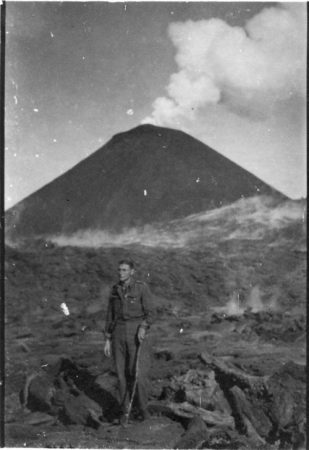

Q: Tell us about this photo of your grandfather. Was he a volcanologist, too?

“My grandfather is standing at the foot of Mt. Vesuvius. He wasn’t a volcanologist, though he was a high school science teacher and a conservationist. The photo of Vesuvius was always one of his favorites, from a time when photographs were quite rare, and he often showed it to me in my youth.”