John Gierke shares his knowledge on Husky Bites, a free, interactive webinar this Monday, September 20 at 6 pm ET. Learn something new in just 20 minutes (or so), with time after for Q&A! Get the full scoop and register at mtu.edu/huskybites.

What are you doing for supper tonight, Monday 9/20 at 6 ET? Grab a bite with Dean Janet Callahan and John Gierke, Professor of Geological and Mining Engineering and Sciences at Michigan Tech. “The water we drink comes from geologically unique places,” he says. As a hydrogeologist, Gierke uses his expertise in teaching and research, and in places around the globe, most recently, El Salvador. Also on his own blueberry farm located about 20 minutes from campus.

Joining in will be fellow colleague and friend, Eric Seagren, a professor of Civil, Environmental and Geospatial Engineering who specializes in finding new, sustainable ways to clean up environmental pollution, including contaminated groundwater.

As a hydrogeologist, Gierke studies the “spaces” in rocks and sedimentary deposits where water is present. Although groundwater is everywhere, Keweenaw geology makes accessing it truly challenging.

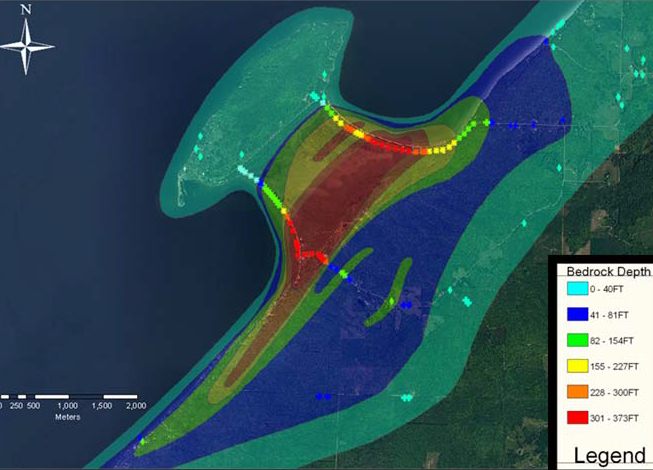

“Drilling productive wells in the Keweenaw is like finding needles in (geologic) haystack,” he says. “Groundwater supplies for many communities are in ancient bedrock valleys that were carved by glaciers and later backfilled with sands, gravels, and, sometimes, boulders left by the melting glaciers in their retreat. In the Midwest, groundwater exists almost everywhere, but in the Western Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and northern Wisconsin and Minnesota, the close proximity of ancient bedrock makes drilling trickier.”

During Husky Bites, Prof. Gierke will show us the inside of some especially interesting aquifers and wells—how they are found and developed, and why some rock formations yield water, and others don’t yield very much.

“Community water wells in Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula tap places ancient glaciers carved and filled.”

“Imagine a 400′ deep glacial tunnel scour back, filled with sands, gravels, silts and clays and capable of yielding 400-some gallons per minute,” says Gierke. “Wells located just outside that ‘trough’ are stuck in bedrock, only capable of giving up hardly 20 gpm, only enough for a single household.”

“The replenishment rate of groundwater in the Copper Country, like much of the northern Midwest, is sufficient that groundwater exists almost everywhere,” adds Gierke. “The challenge in terrains like the Keweenaw, where bedrock is often near the surface, is not whether groundwater exists at depth, but rather where the geology is sufficiently porous and/or fractured to allow water wells to produce at rates sufficient for communities.”

For Prof. Seagrean, at Michigan Tech his major research focus is the bioremediation of contaminated groundwater, especially contaminants like petroleum products and chlorinated solvents. He studies the release of remedial amendments, such as oxygen, added to stimulate the biodegradation of contaminants.

“An amendment is added to a well, and then just released into the natural flow of groundwater without pumping,” he explains. Much of this work involves the use of lab-scale model aquifers. Seagren believes it can be very effective, affordable, and safe way to solve the problem. According to the USGS, more than one in five (22 percent) groundwater samples contain at least one contaminant at a concentration of potential concern for human health.

Seagren also develops and tests low-impact, bio-geoengineering practices to stabilize mine tailings and mitigate toxic dust emissions. “These approaches mimic and maximize the benefits of natural processes, with less impact on the environment than conventional technologies,” he says. They may also be less expensive.”

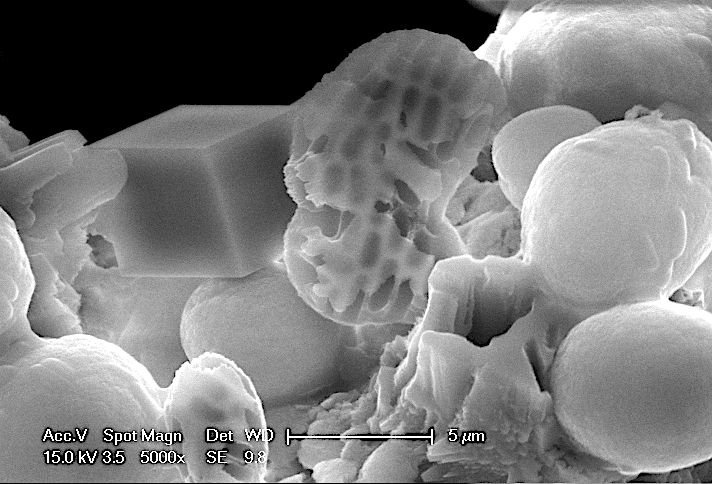

Seagren and his research team zeroed in on a natural process, microbially-induced calcium carbonate precipitation —an ubiquitous process that plays an important cementation role in natural systems, including soils, sediments, and minerals.

Prof. Gierke, how did you first get into engineering? What sparked your interest?

I began studying engineering at Lake Superior State College (then, now University) in the fall of 1980, in my hometown of Sault Ste. Marie. In those days their engineering program was called: General Engineering Transfer, which was structured well to transfer from the old “Soo Tech” to “Houghton Tech,” terms that some old timers still used back then, nostalgically. I transferred to Michigan Tech for the fall of 1982 to study civil engineering with an emphasis in environmental engineering, which was aligned with my love of water (having grown up on the St. Mary’s River).

Despite my love of lakes, streams, and rivers, my technical interests evolved into an understanding of how groundwater moves in geological formations. I used my environmental engineering background to develop treatment systems to clean up polluted soils and aquifers. That became my area of research for the graduate degrees that followed, and the basis for my faculty position and career at Michigan Tech, in the Department of Geological and Mining Engineering and Sciences (those sciences are Geology and Geophysics). My area of specialty now is Hydrogeology.

Hometown?

I grew up in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, where I fished weekly, sometimes daily, on the St. Mary’s River. Sault Ste. Marie is bordered by the St. Mary’s River on the north and east. In the spring, summer and fall, I fished from shore or a canoe or small boat. In the winter, I speared fish from a shack just a few minutes from my home or traveled to fish through the ice in some of the bays. I was a fervent bird hunter (grouse and woodcock) in the lowlands of the Eastern UP, waterfowl in the abundant wetlands, and bear and deer (unsuccessfully until later in life).

What do you like to do in your spare time?

I live on a blueberry farm about 20 minutes from campus in Chassell, Michigan. It’s open to the public in August for U-Pick. For the farm, I used my technical expertise to design, install, and operate a drip irrigation system that draws water from the underlying Jacobsville Sandstone aquifer.

How do you know your co-host?

Eric Seagren and I have been disciplinary colleagues for over 2 decades. Our expertise overlaps in terms of how pollutants move through groundwater.

Prof. Seagren, how did you first get into engineering? What sparked your interest?

I was attracted to environmental engineering because of my interest in protecting human and environmental health. The use of a broad range of sciences within environmental engineering also appealed to me. Growing up we had a family friend who was a civil engineer, and my Dad had a cousin who was an electrical engineer. My Dad himself had wanted to be an engineer, but he had gone to a one-room country school and a small-town high school, and when he got to college they told him he did not have an adequate background in math and science to pursue engineering, something we would never tell a student today!

Anyway, that might have influenced me some, but more importantly was my interest in protecting the environment. I had always spent a lot of time outdoors, either at my grandparents’ farm, or hunting and fishing with my Dad and friends and camping in Scouts. I took an environmental studies class in high school and that’s where I first learned about environmental engineering.

Hometown, family?

I grew up in Lincoln, Nebraska, and earned my undergraduate degree at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. Currently I live in Hancock, with my family, which includes my wife Jennifer Becker, who is also a faculty member at Michigan Tech, and my two teenage children, Ingrid and Birk. We have a cat named Rudy.

Any mentors in your life who made a difference?

Back when I was in college, most people got an undergraduate degree in civil engineering and then pursued a graduate degree in environmental engineering, and that is the path I took. While I was doing my undergraduate work at the University of Nebraska there was a young professor named Dr. Mohamed Dahab who really influenced me and took an interest in me and my career path to this day. He was a great mentor and example for me, and that’s contributed to how I try to mentor students, too.

Any hobbies?

In my spare time I like to garden, do home repairs, hike, fish, boat, run, and Nordic ski. I’m also fixing up a ‘53 Chevy pick-up from my grandpa’s farm. We used to use the truck to haul grain from the farm to the elevator in town. It’s a nice shade of blue. Next summer we hope to fill the back with blueberries from John’s farm and enter it into a local parade.