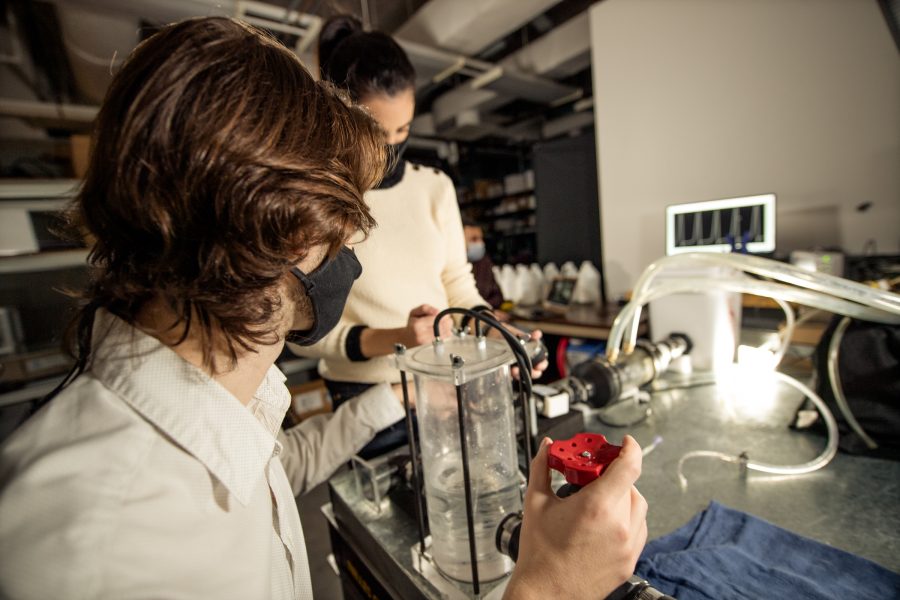

Assistant Professor Hoda Hatoum conducts cardiovascular research with a team of students in her Biofluids Lab at Michigan Tech. One of those students, Brennan Vogl, first started at Michigan Tech as an undergraduate student studying biomedical engineering. Brennan is now pursuing his PhD, with Dr. Hatoum serving as his advisor. Brennan’s research focus is cardiovascular hemodynamics, the study of how blood flows through the cardiovascular system.

Prof. Hatoum, Brennan and her research team—six students in all—research complex structural heart biomechanics, develop prosthetic heart valves and examine structure-function relationships of the heart in both health and disease.

To do this, they integrate principles of fluid mechanics, design and manufacturing with clinical expertise. They also work with collaborators nationwide, including Mayo Clinic, Ohio State, Vanderbilt, Piedmont Hospital and St. Paul’s Hospital Vancouver.

“It is a great pleasure to work with Brennan,” says Dr. Hatoum. “He handles multiple projects, both experimental and computational, and excels in all aspects of them. I am proud of the tremendous improvement he keeps showing, and also his constant motivation to do even better.”

“When a student first joins our lab, they do not have any idea about any of the problems we are working on. As they get exposed to the problems, they begin to add their own valuable perspective. The student experience is an amazing one, and also rewarding,” she says.

“One of my goals is to evaluate and provide answers to clinicians so they know what therapy suits their patients best.”

Prof. Hatoum earned her BS in Mechanical Engineering from the American University of Beirut and her PhD in Mechanical Engineering from the Ohio State University. She was awarded an American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship, and completed her postdoctoral training at the Ohio State University and at Georgia Institute of Technology before joining the faculty at Michigan Tech in 2020. Brennan was the first student to begin working with Dr. Hatoum in her lab.

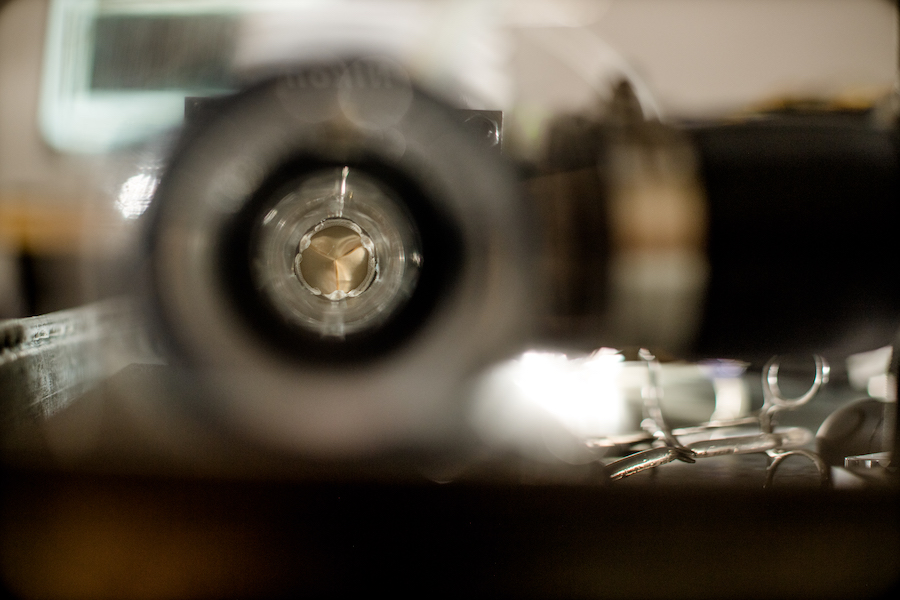

One important focus for the team: studying how AFib ablation impacts the heart’s left atrial flow. Hatoum designed and built her own pulse duplicator system—a heart simulator—that emulates the left heart side of a cardiovascular system. She also uses a particle image velocimetry system in her lab, to characterize the flow field in vessels and organs.

AFib, or Atrial fibrillation is when the heart beats in an irregular way. It affects up to 6 million individuals in the US, a number expected to double by 2030. More than 454,000 hospitalizations with AFib as the primary diagnosis happen each year.

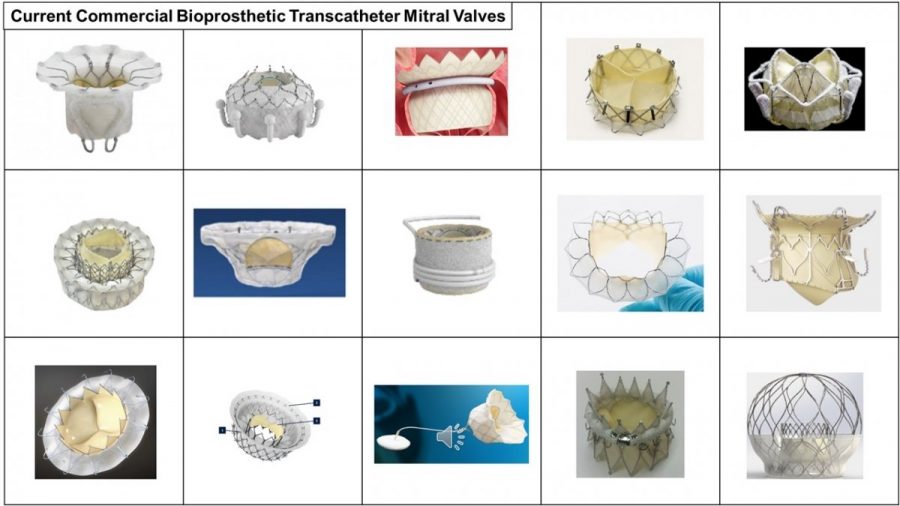

Another focus for Dr. Hatoum and her team: developing patient-specific cardiovascular models. The team conducts in vitro tests to assess the performance and flow characteristics of prosthetic heart valves. “We test multiple commercially-available prosthetic heart valves, and our in-house made prosthetic valves, too,” says Hatoum.

“Transcatheter bioprosthetic heart valves are made of biological materials, including pig or cow valves, but these are prone to degeneration. This can lead to compromised valve performance, and ultimately necessitate another valve replacement,” she notes.

To solve this problem, Hatoum collaborates with material science experts from different universities in the US and around the world to use novel biomaterials that are biocompatible, durable and suitable for cardiovascular applications.

“Every patient is very different, which makes the problem exciting and challenging at the same time.”

The treatment of congenital heart defects in children is yet another strong focus for Hatoum. She works to devise alternative treatments for the highly-invasive surgeries currently required for pulmonary atresia and Kawasaki disease, collaborating with multiple institutions to acquire patient data. Then, using experimental and computational fluid dynamics, Hatoum and her team examine the different scenarios of various surgical design approaches in the lab.

“One very important goal is to develop predictive models that will help clinicians anticipate adverse outcomes,” she says.

“In some centers in the US and the world, the heart team won’t operate without engineers modeling for them—to visualize the problem, design a solution better, improve therapeutic outcomes, and avoid as much as possible any adverse outcomes.”

Dr. Hatoum, which area of research pulls your heartstrings the most?

Transcatheter aortic heart valves. With the rise of minimally-invasive surgeries, the clinical field is moving towards transcatheter approaches to replace heart valves, rather than open heart surgery. I believe this is an urgent field to look into, so we can minimize as much as possible any adverse outcomes, improve valve designs and promote longevity of the device.

How did you first get into engineering? What sparked your interest?

As a high-school student, I got the chance to go on a school trip to several universities and I was fascinated by the projects that mechanical engineering students did. That was what determined my major and what sparked my interest.

Hometown, family?

I was raised in Kab Elias, Bekaa, Lebanon. It’s about 45 kilometers (28 miles) from the Lebanese capital, Beirut. The majority of my family still lives there.

Brennan, how did you first get into engineering? What sparked your interest?

I first got into engineering when I participated in Michigan Tech’s Summer Youth Program (SYP) in high school. At SYP I got to explore all of the different engineering fields and participate in various projects for each field. Having this hands-on experience really sparked my interest in engineering.

Hometown, family?

I grew up in Saginaw, Michigan. My family now lives in Florida, so I get to escape the Upper Peninsula cold and visit them in the warm Florida weather. I have two Boston Terriers—Milo and Poppy. They live with my parents in Florida. I don’t think they would be able to handle the cold here in Houghton, as much as I would enjoy them living with me.