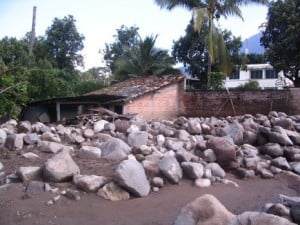

In October 2011, heavy rainfall poured down the sides of El Salvador’s San Vicente Volcano, nearly four feet of water in 12 days. Coffee plantation employees, working high up on the volcano’s slope began noticing surface cracks forming on steep slopes and in coffee plantations. Cracks herald landslides—places where the wet, heavy upper layers, saturated with water, slide over the less-permeable rocky layers underneath. The workers radioed downslope, keeping close tabs on the rainfall gauge network.

In October 2011, heavy rainfall poured down the sides of El Salvador’s San Vicente Volcano, nearly four feet of water in 12 days. Coffee plantation employees, working high up on the volcano’s slope began noticing surface cracks forming on steep slopes and in coffee plantations. Cracks herald landslides—places where the wet, heavy upper layers, saturated with water, slide over the less-permeable rocky layers underneath. The workers radioed downslope, keeping close tabs on the rainfall gauge network.

Luke Bowman was also there, helping direct radio calls and conducting fieldwork. Bowman, who recently defended his doctoral research in geology at Michigan Technological University, studies geohazards on San Vicente. The Journal of Applied Volcanology recently published some of his research, co-authored by Kari Henquinet, director of the Michigan Tech Peace Corps Master’s International Program and a senior lecturer in the Department of Social Sciences. Their work combines traditional hazard assessments with social science techniques to develop a more in-depth understanding of the risks present at San Vicente Volcano in El Salvador.

Ethnography

Incorporating social science techniques—like ethnographic interviews and participatory observations of community meetings—is no easy feat for physical scientists, who have not been trained to think that way. Collaboration is important, and Henquinet worked with Bowman on his volcanology research to round out his social science data gathering methodology.

“The ethnographic approach is immersion,” Henquinet says, explaining researchers have to learn in the field and adjust their work accordingly. “It’s an approach that’s exploratory, grounded in reality and the context that people live in, so you’re not isolating or manipulating an experiment in a lab.”