If you haven’t read our prior installment in a Murder in Dollar Bay, you will want to catch up on that before finding out how the story ends. Please note that this blog post describes fatal injuries in some detail.

Marian Doyle was dead. Addison Aldrich didn’t need his medical degree to know that.

The body lying on the table at the Plowe Funeral Home had grown stiff. Dr. Aldrich touched his fingers to Marian’s wrist and found it cold as ice. There was no pulse. His thoughts almost certainly drifted for a moment to his new wife, Geraldine Ann, who was only a few years older than Marian. Aldrich himself was not yet thirty and had been practicing medicine for just three years. As a physician and an assistant to the county coroner, he had long since lost any youthful pretense of immortality, but seeing a person so young and brutally wounded–well, anyone would find themselves unsettled. Aldrich’s training as a doctor took over, however, and he grimly began a systematic examination of the deceased woman before him.

Aldrich described Marian’s injuries later in a litany. She had been dead about eighteen hours by the time he began the autopsy at 4:30 on Sunday afternoon. “There was old blood present about her mouth and lips,” he said. The scalp bore “many puncture wounds,” and significant lacerations on her forehead extended into the skull, which had been fractured. The severe beating Marian’s jaw had endured dislocated it from the rest of her skull. Her neck and every bone in her face were broken, and countless cuts and contusions crossed her chin, chest, shoulders, neck, and back. Aldrich carefully considered the somber list and marked the skull fracture and broken neck as the proximate causes of Marian’s death. The injuries, he said, were consistent with being beaten with two heavy objects, one of which had a pointed end–like a flatiron and a stove poker, the bloody or hastily-washed tools discovered at the Pichette house in Dollar Bay.

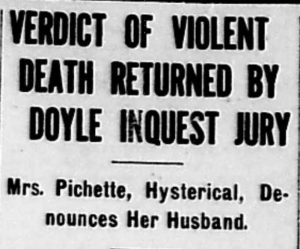

Dr. Aldrich’s report became a cornerstone of a coroner’s jury overseen by his supervisor, David Osborne of Laurium, and Justice Charles E. Rouleau a few days after the murder. On Thursday, October 27, the group concluded that “Miss Marian Doyle came to her death on the night of Saturday, October 22, 1938, in the home of Wilfred Pichette… by being struck on the head and face with a flatiron and a stove poker, causing a fractured skull and broken jaws.” With the body now buried and the cause of death established, the two confessed suspects could be brought to trial.

Of course, in the court of public opinion and in the press, the trial of the Pichettes had begun much earlier.

It isn’t often that a man confesses to murdering a woman because she was the devil or a witch; it’s rarer still that his wife insists upon the same rationale. In a town like Dollar Bay–quiet, close-knit Dollar Bay–it’s unthinkable. Yet it happened. The strange story, circulated among neighbors and law enforcement, slowly spread outward. The Daily Mining Gazette picked it up; so did newspapers in Benton Harbor, Marshall, Wausau, Madison, and other Great Lakes towns. Even readers in far-off states like Montana, Texas, and New Jersey could thrill to the latest news of the case, once journalists from the Associated Press had penned their reports. As the tale spread, it grew. New details, of varying degrees of credibility, became part of the legend. Norma Pichette, the seven-year-old daughter, had told her parents to stop hurting Marian but had been forced to watch, helpless, as they beat her to death. The Pichettes had allegedly gone to a priest in Calumet and told him that they “exerted a mysterious power over a victim at their home.” Stranger still was the story of Wilfred and the Gypsies. Depending on which reporter had gotten hold of the rumor, he had paid a fee of up to $2,000–maybe even borrowed from his mother-in-law–to purchase divine powers from them. Who these mysterious traveling salesmen might have been, or how they were supposed to have obtained these powers in the first place, went unexplored.

With fertile ground for the imagination laid by these stories, the papers overflowed with detailed descriptions of Wilfred and Laura’s behavior in the jail, at the courtroom, before the press. Each movement, each statement, provided another example to the reporters of the couple’s mental instability and inclination to evil. Ample attention was paid to Wilfred’s apparent confinement in a padded cell at the jail, as well as his methodical removal of his socks and shoes during an appearance before the judge. At the coroner’s inquest, he was reported to have stared straight ahead, flinching only when Laura broke down. The press coverage had attracted some five to six hundred people to wait in the street outside the courthouse, gawking as the Pichettes were led inside from the jail. Until that point, Laura had been remarkably composed, but the crowds apparently pushed her over the edge. “I don’t want to be tortured by him any more,” she cried out in the courtroom, referring to her husband. “He just talks of devils and curses.” She professed fear of the crowds, especially that they were laughing at her. She wanted the trial over and done.

Perhaps Laura’s fear of being before all the people in court, and the Pichettes’ mutual understanding that a lawyer, even if they could have afforded one, would have had a difficult time building a defense, led to the couple’s decision to plead guilty. Witnesses were still called to the circuit court to give their testimony, among them the two deputies who had investigated the crime scene, Dr. Aldrich, Laura’s mother, and, shockingly, seven-year-old Norma Betty Pichette.

Picture little Norma perched in the witness stand, her legs swinging over the edge of a chair too tall for a child of her age. She told the prosecutor that she was going to school but not at that moment, just the kind of response a second grader would give when asked if she goes to school. Her matter-of-fact, innocent answers soon gave way to something darker when the attorney asked what happened on the night of Saturday, October 22, in the family home. Her parents had said that Marian “was full of devils,” Norma replied. “We were all kneeling up by the chair by the window and my father told Marian to keep her hands up in the window. Marian didn’t want to. He knocked her off the chair, broke her neck, and filled her mouth full of tobacco and then he told my mother to go get the irons. If she didn’t he would kill her.” Laura brought the objects that Wilfred had demanded, Norma said, and then they both began to beat the woman until they were certain she was dead. Afterward, all three Pichettes–including little Norma–had to carry Marian upstairs to the bedroom where deputies discovered her the following morning.

A child of seven being called to testify against her parents in a murder case spoke to a deep undercurrent of trouble in the family, and the girl’s eyewitness account of the murder no doubt helped to seal the fate of the Pichettes. On November 16, the couple officially entered their guilty pleas, grimly accepting whatever punishment the court felt appropriate to hand them.

Why did the Pichettes kill Marian Doyle? It does appear that Wilfred, at a minimum, felt a genuine conviction that Marian needed to die. Perhaps, in a moment of shame over his affair with her, he conceived the idea that witchcraft on Marian’s part had led him to the decision and that she was a threat. If nothing else, he certainly insisted to Prosecuting Attorney Frank Condon that Marian had induced him to cheat on his wife, that she had been flirting with him since the start of her employment and that he had been powerless to resist. Condon found the explanation unconvincing. “In reading between the lines,” the attorney wrote, “it would seem that the motive for the crime was his belief that Marion [sic] was pregnant as the result of the intercourse he had had with her and that he wished to dispose of her.” He had not killed her because of insanity nor “any lack of possession of his faculties or reasoning powers except when he got off on to the religious tangent that he was possessed of all power.” Condon maintained that Wilfred had been “perfectly sane at the time the crime was committed,” as well as when he entered his guilty plea. No clemency.

Although Laura Pichette admitted to her participation in the murder, she maintained from the early days of the investigation that she had not killed Marian of her own volition but had only participated out of fear of her husband. Condon also thought Laura’s persistent statements that she had had no choice unpersuasive. “She may have been somewhat afraid of the result of her refusal,” he reported, “nevertheless she admits that she knew that what she was doing but that she was too weak to refuse or to go to her mother who lived in the same town.” Condon deemed Laura to have been “sane and under no duress or sufficient compulsion at the time of the crime to excuse her.” He went even further, speculating that Laura had “joined [Wilfred] in the crime… because of jealousy and having returned from an absence during which she had been living in adultery, she wished to do all that she could to comply with his wishes.” In the end, whether Laura were complicit or Wilfred were sane, Marian Doyle was still dead, and the killers still had to pay for their crime.

At ten o’clock in the morning of November 17, 1938, Wilfred and Laura Pichette were both sentenced to life in prison. Laura was to serve her term in the Detroit House of Corrections, a facility that accepted women, while Wilfred was to be confined to the Marquette Branch Prison. Both journeyed to their new places of residence later that same day, leaving behind their daughter and the home that had become a place of such violence.

True to the drama of the Pichette case, however, a few twists yet remained. In May 1939, about six months after her sentencing, Laura Pichette’s name once again appeared in the newspapers. Her story no longer demanded banner headlines but rather found itself tucked away on the inner pages, banished to the section reserved for head-shaking curiosities. Staff at the Herman Kiefer Hospital, a medical center owned by the City of Detroit, reported that Laura had given birth to a healthy son weighing seven-and-a-half pounds. He would be adopted, according to the La Crosse Tribune, “by relatives of the Pichettes.” Given the timing of the birth, it seems almost certain that the boy was not the son of Wilfred Pichette but of Laura’s former paramour, Russell Cassidy. With any luck, the child was able to disappear into obscurity and happiness under the care of his adoptive parents. After some years in Marquette’s Holy Family Orphanage, his sister Norma Betty Pichette did the same. She changed her name, attended Northwestern High School in Detroit, and married in 1950. In 1998, she died in Phoenix, Arizona, where she had been living for the past several decades.

Although Prosecutor Condon had maintained that both Wilfred and Laura Pichette were sane–or at least sane enough to be considered legally culpable–Laura was transferred to the Ionia State Hospital, which helped to treat felons and civilians alike with mental health problems, in 1942. “Severe hallucinations,” according to her official record, led to the move. At Ionia, psychiatrists diagnosed her with “schizophrenia, chronic undifferentiated type,” per a summary of her files prepared subsequently. Laura underwent an extensive sequence of treatments, some of which reflected the vogue of the day: “individual and group therapy, chemo therapy, electro-convulsive therapy, and occupational therapy. She has shown varying degrees of cooperation and response.” In 1955, Wilfred Pichette also became an inmate at the Ionia State Hospital, for reasons unknown. His time in prison remains distinctly hazier than Laura’s, but it is certain that he died there in January 1969. Whether the Pichettes, who remained married, might have seen each other in their shared captivity is a mystery.

The Ionia State Hospital changed in 1972. Patients not held on criminal counts moved to new homes. Laura Pichette took the opportunity of the shift to petition the Parole Board of the Michigan Department of Corrections for commutation of her sentence. Asked what in her life would enable her to make a good social adjustment to the world beyond after so many years, she replied, “The circumstances of my life are changed for the better due to my age and widowhood. I came to my senses and realize my daughter really wants me.” Evidently, Norma had been able to forgive her mother and work beyond the trauma of her early years. Laura argued, as she had in 1938, that her participation in Marian Doyle’s murder had been involuntary, saying that “I was physically forced by [Wilfred] to participate, terrorized to do anything else but follow his orders.” These factors, she said, combined with “ill health and age” that had rendered her dependent on others and thus no longer a threat to society, should justify her release. After some consultation with the Ionia State Hospital, the Parole Board agreed. Laura received her commutation and was discharged on November 1, 1973, to move in with her daughter and son-in-law in Arizona.

With her release, Laura vanished into the mists of time. At this juncture, no verifiable information about her life after commutation can be obtained. The murder of Marian Doyle, too, faded into obscurity. No longer on the lips of Dollar Bay residents or plastered on the front page of the Daily Mining Gazette, it became one circuit court case file among thousands in the Michigan Tech Archives or included in anthologies of alleged witchcraft incidents. The story of Marian Doyle’s violent death, like so many other fascinating and occasionally disturbing annals of Copper Country history, was waiting to be told again.

WOW It makes my skin crawl at the thought of such a horrible crime,and I marvel at how the child could forgive her mother. What is a mystery to me is that she should get a commutation for her crime. Surely they were both as guilty as all can see.Writer you have shared a real slice of life albeit a violent one in a story that has captivated so many. Call it morbid curiosity if you will I wait to see what new fascinations the archives sends our way next!

Fascinating local history – true crime story. I am curious to hear more as well.