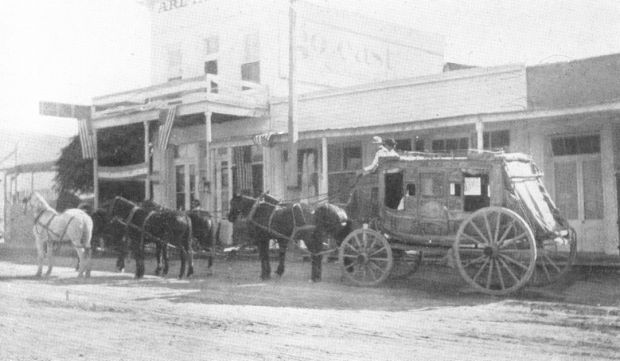

“Donate,” Reimund Holzhey said. “I’m collecting.” He raised a revolver in each hand and cocked them at the stagecoach. It was late August 1889 in Gogebic County, and although the coach had been traveling along the road from Lake Gogebic, cool breezes were hardly guaranteed. If the four stagecoach passengers had not already been sweating, they certainly were now. On their journey to Gogebic Station–a stop along the Milwaukee, Lake Shore, and Western Railroad twelve miles east of Marenisco–they had crossed paths with the type of criminal more common to the Wild West than the western Upper Peninsula. Holzhey, a young man in his twenties, had made his move boldly and confidently, like someone with experience in theft.

One man, however, kept a cool head. The would-be victims were mostly Chicago residents; violence marked that city more than most American towns. Unfortunately, his hand was not as steady as his head. “All right,” he said. “Here’s mine.” He drew his own revolver and squeezed off a round, which flew wide of Holzhey. That was enough for the stagecoach robber, who emptied his guns in the direction of the men. Two more reports from the first passenger’s revolver missed Holzhey, though he stood just five feet away. One of the others aboard, however, took bullets to his face and his leg, wounds that the Ontonagon Miner described as “not necessarily fatal.” Adolph Gustavus Fleischbein was not as lucky. The bullets that hit him in the left thigh traveled upward, entering his bowels. Fleischbein fell from the stagecoach, landing in the dirt. Spooked by the shooting and by the driver’s belated attempts to hurry them away, the horses hitched to the coach bolted, wildly dragging the vehicle down the wooded path. As they faded into the distance, Holzhey crept over to the gravely-injured Fleischbein, seized his pocketbook and jewelry, and left him to die in the road.

Two long hours later, help returned for Fleischbein. The rescuers took him to the hospital at Bessemer, where his wounds were cleaned and dressed. It was clear to everyone, however, that he had lost far too much blood to have any hope of survival. “He cannot recover,” as the Miner put it. Telegrams flashed over the wires to Belleville, Illinois, notifying Mrs. Fleischbein of her husband’s imminent demise. Meanwhile, County Attorney Howell took Fleischbein’s sworn statement about the robber and his actions on the road from Lake Gogebic. Fleischbein said that, as the stagecoach disappeared from view, Holzhey had come up and held a gun to Fleischbein’s face, threatening to kill him then and there. Fleischbein, no doubt thinking of his wife and teenage daughter, “pleaded hard for mercy,” according to a summary of his testimony published in the Chicago Tribune. The robber agreed to spare his life–a gesture rendered moot by the fact that his bullets had already ensured Fleischbein’s death. At six o’clock the next morning, “Dolph” Fleischbein–a Civil War drummer boy, former public servant, and enthusiast of hunting and fishing–died.

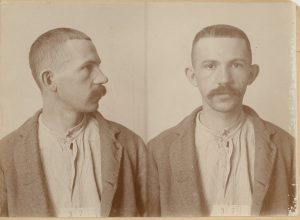

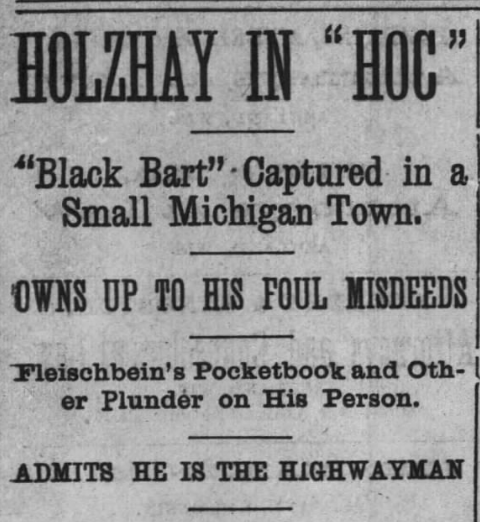

With Fleischbein’s death, the manhunt for Holzhey went from a search for a thief to a search for a murderer. Deputies had already been posted along roads and at train stations in Gogebic County, their eyes peeled for a man “small in stature, with a dark, curling mustache, of medium height, slight build, and dressed in light clothes.” The description Fleischbein and the others on the stagecoach gave confirmed the lawmen’s grim suspicions: the robber, whose true identity me remained unknown at the time, was “Black Bart.” Black Bart had bedeviled Wisconsin highways and railways for months, brazenly making his criminal forays under the noses of lawmen. Two months before he ventured into Gogebic County, the Wood County Reporter of Wisconsin reported that the highwayman had robbed three stage coaches, a Milwaukee and Northern passenger train, the sleepy general store of Bonduel, and a man traveling by buggy back to the reservation where he lived. He also had the nerve to rob the home of a judge. Despite the promise of a $500 reward offered by the Milwaukee & Northern general manager, the posse that pursued him through Shawano County had no success. After the Gogebic robbery and Fleischbein’s murder, the railroad offered a new reward of one thousand dollars, along with contributions from Gogebic County and Fleischbein’s home county.

Members of the manhunt tracked Holzhey that night for six miles from the stagecoach road to a stream, where they lost the trail. Two bloodhounds and a local Ojibwa man with tracking skills joined the search the following day. It was clear that Holzhey had headed north from Gogebic Station, but his whereabouts grew murkier after that. In fact, Holzhey had turned east, bound for the iron mines of Marquette County.

On August 31, a Mr. Glode, City Marshal for the town of Republic, and Justice of the Peace E.E. Weiser left their homes early, strolling in the direction of the railroad depot. As they walked past the terminal, “a man dressed roughly and apparently anxious to escape attention” caught Glode’s eye. As a lawman, he had been apprised of the hunt for Holzhey and of the thief’s appearance. The stranger in town was short, slightly built, and possessed of a dark, curling mustache–Glode knew immediately that he needed to approach and question him. The Ashland Weekly News reported that he blocked the other man’s path, saying, “I want you.” Down went the stranger’s hand for the gun that he wore. Marshal Glode was faster, though, and he struck the smaller man with his billy club. Glode and Weiser carried the suspect to the Republic jail.

As the stranger came to, Glode searched his pockets. He removed “three revolvers, three gold watches, four pocket books, and other articles” of value. Holzhey’s name was etched on one of the pocket books; Fleischbein’s was there, as well. Clearly, Glode and Weiser had found their man. Holzhey strongly resisted their questioning at first, but he gradually began to crack. Yes, his name was Reimund Holzhey. Yes, he had been the man who robbed the Gogebic stage and one in Wisconsin. Eventually, he conceded obliquely that those crimes had probably been carried out by the same man responsible for the others attributed to Black Bart. In the presence of the sheriff and marshal, he prepared a statement outlining his lawbreaking past.

Even while Holzhey was being escorted back to Bessemer to face the music, newspapers treated him as something like a celebrity. At least one published a detailed and literary biography, describing his prosperous farmer father back in Germany, Reimund’s desire to make his own fortune, and his interest in the lumber mill where he had worked upon arriving in America. He was said to be a man of few words, little proclivity for alcohol, and a general aversion to trouble–unless someone crossed him. The writer placed blame for Holzhey’s descent into lawlessness on reading too many stories about criminals like Jesse James. He had been so fascinated with tales ripped from the headlines that he was determined to become one himself.

In a fall 1889 trial, the Archives of Michigan reports, a jury convicted Reimund Holzhey of murder. Holzhey served the first part of his sentence in the Marquette branch prison, where he was a disorderly inmate. The American Citizen of Ironwood wrote that he seized a knife from the prison shoe factory and took a guard hostage, demanding his release in exchange for the guard’s life. “In an unguarded moment, Holzhay [sic] dropped his right hand, still holding the knife, on his leg only to have every finger shot off with a bullet from the warden’s gun. This settled the matter for that time and reduced Holzhay’s ability to harm by one hand.”

After nearly four years of increasing difficulty, Holzhey was taken under strong guard to Ionia, home of “the asylum for criminal insane.” There, he underwent some sort of procedure that left him transformed. He came back to Marquette stable, responsible, and eager to work. According to a piece by the Archives of Michigan, he became the official prison photographer, librarian, and newspaper editor before his life sentence was commuted in 1910. Discharged in 1913, Holzhey loped back into the woods that were familiar with him, working at resorts. He headed west to Yellowstone to continue his photography career, then moved to Florida. He died there in 1952 by his own hand, bringing the story of Michigan’s last stagecoach robber to an abrupt conclusion.

Thank you I love to learn the history of these small towns.

Interesting interesting story

This story is very interesting! I guess I never thought of stagecoaches in the U P. Jeez I hope he was not an ancestor of mine. Nicely told story!