“The lands of the Central Mining Company… are bounded on the north by the Copper Falls location, on the east and south by the North Western, and on the west by the Winthrop location, and are four and one half miles from Eagle Harbor… These lands are well timbered with pine and sugar-maple, and have a soil well suited to the wants of a mine, and mine force.”

Optimism overflowed in the opening words of the first annual report of the Central Mining Company, the corporate body responsible for the eponymous Central Mine. Such hope was well-founded. Initial explorations at the mine in 1853 had suggested that copper deposits on the property would be particularly rich, and, just one year after commencing operations, dreams turned to boasting. “The Directors will state that the Central is the first mine yet opened in the Lake Superior district, which produced and sold copper enough, during the first year of its operations, to more than pay all expenses of the Company; and further, no other one has produced so much copper the first year of working.” Central had done the virtually impossible: turned a profit right from the start. In an environment and at a time when the average copper mine would best be described as a failure, Central was remarkable. It always would be. The reasons simply changed.

A mine needed workers. Men arriving on their own–either bachelors or those living apart from their families–constituted the bulk of initial employees. Since mining was marked by unpredictability, and it seemed unfair to drag a wife and children unnecessarily from pillar to post on a frontier, men drifted in, stayed for a while, and moved on to greener pastures when the exploration faltered. Accommodations for the workforce at most mines were sparse: some rough boarding houses or bunkhouses, which could be repurposed when operations wound down, typified an early mine location. At first, Central was no different. The annual report for 1855 described surface improvements as “light.” Along with shafthouses and horse whims, only three houses had been built, thanks, in part, to the struggles of the neighboring Winthrop and Northwestern operations. These rentals would “give accommodation to our force, and render the erection of houses for families… unnecessary” for the time being.

It became apparent quite quickly, however, that Central was not bound to go the way of its neighbors. In 1855, owing to the success but yet the infancy of the mine, “twenty-six miners and twenty surface men” constituted the entirety of the workforce. By 1860, Central began to outgrow the stamping facilities it had rented, was starving for men to keep up with its production, and had to boost wages. Workers responded favorably, and, in the annual report for 1862, the board of directors described the construction of twenty houses “for the accommodation of our mining force,” with an imminent need for homes to be built for “three or four times the present laboring force.” At the end of 1868, an estimated 845 workers and families, largely Cornish, resided at Central; the following year, their number swelled to over 900. Central had become a real town.

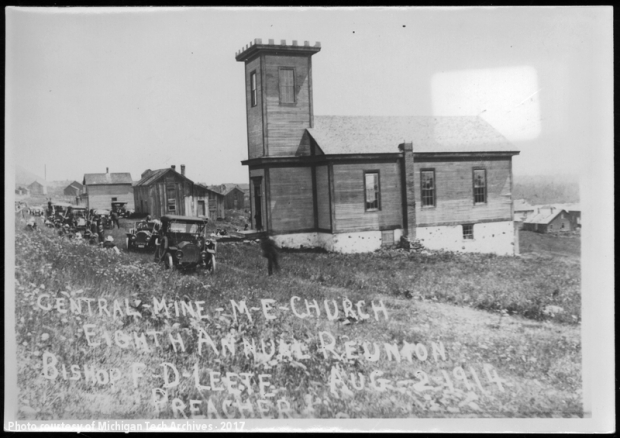

As Central transformed from frontier outpost to mining village, its people sought to bring the comforts and soul of nineteenth-century life to their new home. John Wesley’s Methodist teachings had spread like wildfire across Cornwall, wooing skilled miners and their families away from the Church of England through simple doctrine and revival preaching. The emigrants who crossed the ocean from Kernow to the Keweenaw brought with them a deep faith that wove through every aspect of their lives, and they devoted themselves to establishing a Methodist presence in Central. A small schoolhouse near the Central Mine-Northwestern Mine boundary held early services and Sunday Schools, but, as the mine and town flourished, the congregation’s attention turned to the construction of a proper church. The time came in 1868. “Divine services continue to be regularly held, and some progress has been made toward the erection of a church,” wrote the agent of the Central Mining Company that year. As he penned his report, a wood-frame chapel was rising near the heart of Central. Like most Methodist churches, especially in rural communities, its builders sought simplicity and durability in construction.

A poor-rock foundation was the logical choice. Long pieces of narrow wooden siding gave the outside an appearance of crisp uniformity. Six tall, plate-glass windows–three on the north side of the building and three on the south–cast patterns of sunlight across rows of pine pews. Their high, straight backs discouraged cat naps during Sunday sermons. Cleanly whitewashed walls provided cheer without adornment and a marked contrast to the preacher’s black suit as he stood before his parishioners to exhort them in virtue and faith. Alongside him on a platform spanning the width of the church sat the choir, a pride of Central Mine. These men and women, nestled in spindle-backed chairs, came from a proud Cornish tradition of singing; rich voices soared through the mines of Cornwall, carrying the melodies of beloved hymns, and now they did the same in the Copper Country. On Sundays, a bell in the church tower called the people of Central to worship. The crenelation topping the belfry was the congregation’s great concession to elegance: its sawtooth appearance hearkened back to English castles and made a wilderness more like home.

“A church has been erected at the mine (with the aid of the company), in which services are regularly held,” read the 1869 annual report. It was true that the mining company played a role in constructing the Central Mine Methodist Episcopal Church, but credit for building its vibrant community and its life rested on the shoulders of the people. In the basement, they gathered for Sunday School classes or to peruse the circulating library that its people carefully compiled. Before the new Central school was built, scholars who had overflowed the old schoolhouse studied in the basement, as well. To celebrate Independence Day, the Sunday School–whose attendees regularly numbered over 200 in the 1880s–threw picnics with candy and the enthusiastic Central Cornet band as entertainment. The Saturday before Christmas, Santa Claus visited to distribute “mittens, suspenders, pocket knives, mouth organs, knitted hoods, scarfs [sic]… straight brass horns, circular brass horns, jumping-jacks, dolls, jack-in-the-box… china dolls, sailor dolls, rag-baby dolls… that squeaked, cried, and laughed,” as long-time Central resident Alfred Nicholls remembered. After Christmas carols from the choir, the children were let loose to enjoy their gifts. “From every quarter of the little church,” Nicholls said, one heard “the baa of the sheep, the squeak of the doll,” the “full and active operation” of slide trombones and “fluttering fingers on tin whistles.” The Central church was a place of joy, at Christmas and throughout the year.

Yet the heyday of Central Mine, brilliant as it was, faded too soon. The mine sat upon an uncommonly good deposit of copper, but practicality, accessibility, and profitability eventually dictated that the mine would have to close. After fits and starts, it did so for good in 1898, having produced almost 52 million pounds of copper. “In like fashion,” wrote Central historian Charles Stetter, “did the Central Mine Church close its doors, presumably for good.” But the sense of belonging to Central persisted in the hearts of its people, now scattered to Calumet, Hancock, or Painesdale; the memories of those Christmases, Sunday worship, or Fourth of July picnics did not fade. When, in 1907, the Keweenaw Central Railroad built track that ran as far north as Mandan, Alfred Nicholls saw an opportunity. Why not use the new ease of transport to bring people home to Central? They could gather in the old church for a “Sunday service… strictly religious in character” and conforming “as nearly as possible to the order of worship as was observed in former years,” in the words of Stetter. On July 21, 1907, the first Central Mine reunion was held at a church packed to bursting. Throughout the day, visitors sipped coffee and tea, chatted with friends, and walked down paths they had trod so often in Central’s earlier life.

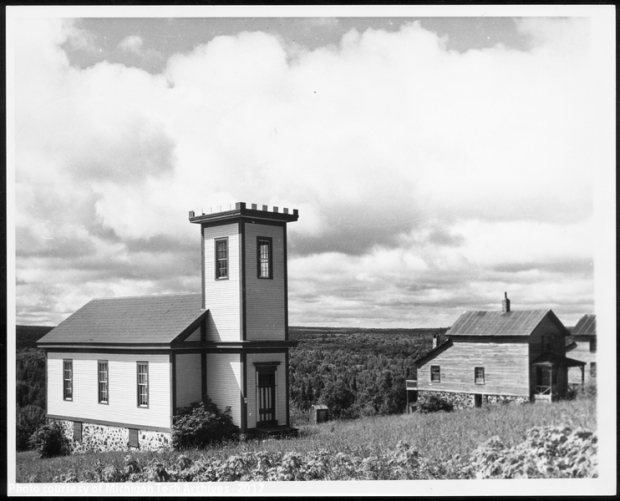

Time passed. The old residents of Central passed, too, and the buildings at the old mine fell into increasing disrepair. Dozens of houses that had formed the neighborhoods of Central collapsed or were torn down. Heavy snows claimed the roofs of the powderhouse, the engine house. Trees crept back onto the deforested hillside. Yet the church remained, its bell tower still proudly proclaiming Central’s Cornish heritage, and the children and grandchildren returned on the last Sunday in July, year after year. Even as war raged in Europe–not once but twice–and as the country plunged into the throes of the Great Depression, even as the greatest mines of the Copper Country fell silent, for good, Central’s people came back. The records of the church note no interruptions from 1907 on.

The character of the service changed, growing more ecumenical, and responsibility for leading worship was laid in the hands of a series of ministers. One man, however, left his mark on the church in the wildwood more than any other preacher. In 1984, and then annually from 1990 to 2018, the Rev. Dr. Daniel “Dan” Rosemergy’s boisterous laughter and contagious enthusiasm flooded Central. Like the men who had played Santa Claus at Central Christmases, he distributed gifts to children in the form of Cornish flags and currant cookies; he sang in a quartet of Cornish voices in the midst of each service and beamed as the congregation burst into “All Hail the Power of Jesus’ Name,” the Diadem setting. His messages encouraged fellowship, compassion, kindness, and joy. Every attendee at the reunions left richer for having met him. And when Dan Rosemergy went to join his Central ancestors in 2019, he left behind a deep conviction in their hearts that the reunions would continue. July 26, 2020 will be the 114th year.

What brings people back to Central? What makes them feel that they belong to this place, even if they have never lived there, and their last family member moved away a century or more ago? Is it the stillness that one feels on a winter afternoon, standing in the doorway of the powderhouse? Is it the view that spreads out from the front porch of an old red house? Is it the peace that settles on a person, looking north from the poor rock pile? Is it the rustle of leaves on a summer day, the wind whispering through them like it has a secret to tell? Is it the music of the old pump organ and the Cornish voices raised in song on those July mornings, the chime of the bell calling all into the church? Is it the sense that the gap between today and yesteryear is much narrower on the dusty streets of Central? Perhaps what defines Central cannot, itself, be defined. Perhaps it can simply be lived.

Come to the church in the wildwood,

oh, come to the church in the dale;

no spot is so dear to my childhood,

as the little brown church in the vale.

–William S. Pitts

My great grandfather came from Cornwall England with his family. My Grandfather was born in Central Mine and mined when he was 10 years old when his Father fell in the mine and broke his back.

I am proud to say I HAVE BEEN TO THE CENTRAL REUNION and the writer is correct Pastor Dan sure had a way about him. I know some folks that find Central strangely and sort of mystically compelling to come to that church in the wildwood I enjoyed this article

Very interesting and well written.

I nice compact history of Central

Beautifully written. One must experience Central to truly understand.