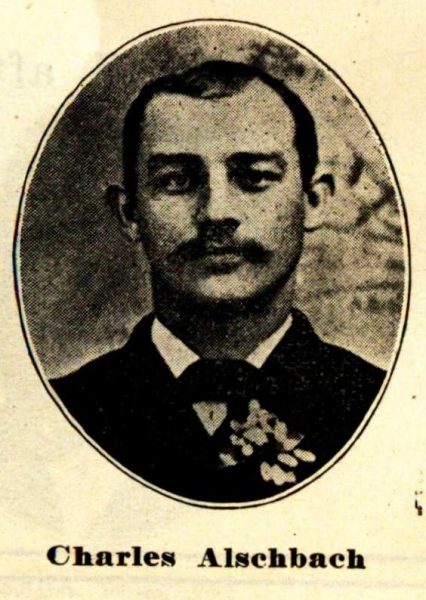

In 1916, Calumet & Hecla celebrated its semicentennial in grand fashion. The company normally abhorred any stoppage in work not demanded by market conditions, making its decision to halt work for the July 15 festival particularly remarkable. That day, star-spangled banners fluttered on buildings and bandstands throughout Calumet, and workers–male and female alike–marched through the streets to the acclamation of spectators. Near the head of the parade walked Charles Alschbach. At Calumet’s “commons” (later Agassiz Park), he and his peers listened as Michigan Governor Woodbridge N. Ferris feted the success of Calumet & Hecla. They dined on lunches provided by the company–some 19,000 of them. Then, at two o’clock, C&H President Rodolphe Agassiz rose to salute the loyalty, efficiency, and service of the company’s longtime employees. Concluding his speech, he invited Alschbach and 168 of his peers to come forward so that he might present them with gold medals honoring 40 to 50 years of employment at C&H. Spectators who obtained copies of The Keweenaw Miner’s commemorative program could peer at the photographs provided of “Gold Medal Men” and see Alshbach among them. A mustachioed man with a receding hairline, he looked proud to stand before the camera in his dress suit. He was the epitome of a model employee.

Which makes his abrupt termination two years later even more remarkable. Remarkable, perhaps, but very much of its time.

Charles Alschbach was born in about 1860 in Eagle River. The 1870 census found him residing there as the second son in a family of seven children. His father, George, worked as a stone mason; his mother, Caroline, tended to the home. Although Charles’s older brother, Henry, and sister, Catherine, were both recorded as “at school,” Charles was not. Perhaps the nine-year-old’s first census offered a glimpse of his life soon to come.

In 1874, the Alschbach family moved from Keweenaw County down to Lake Linden. While the northern county had been a nexus of copper mining in the early days, the geography of the Copper Country had shifted since Charles’s birth. First the Hulbert Mining Company and then its two child organizations–the Calumet Mining Company and the Hecla Mining Company–began to work one of the richest copper deposits in the world, located in northern Houghton County. After original operator Edwin Hulbert blundered his way through the first years, the board of directors of the Calumet and Hecla companies ousted him in March 1867 and installed Alexander Agassiz, father of Rodolphe, as superintendent instead. The two companies, which quickly became profitable, merged in 1871 but counted their original, separate birthdates of 1866 as their shared founding year.

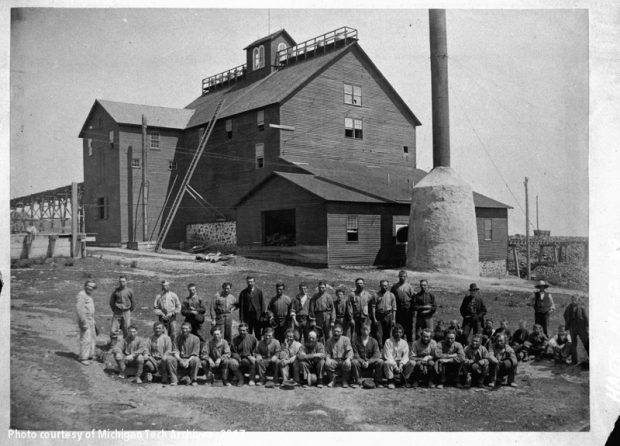

Successful mines reaping copper-bearing rock–and up to 15 percent of what came out of C&H’s early workings was copper, a remarkable sum–needed a place to mill it, separating the valuable metal from the poor rock and preparing it to be smelted into ingots. Ready access to water made the critical difference between making money and losing it: the copper needed to be washed and to be crushed under steam-powered hammers, and some early mines faltered for placing their mills in poor locations. C&H chose more carefully. Between 1868 and 1870, first the Hecla and then the Calumet mining companies built stamp mills on the shores of Torch Lake. Men flocked to work at the mills, and the town of Lake Linden grew up in their shadow.

Charles Alschbach and his family arrived during this early boom. Although Lake Linden already had a school, constructed with the eager support of its residents, his thoughts and priorities lay elsewhere. In 1875, at fourteen or fifteen years old, he walked into the C&H employment office and applied for a job.

Child labor had long been tightly bound up with copper mining. In Cornwall, where mining predated the birth of the industrial Copper Country by centuries, whole families regularly went to work at the local mine together. Children, daughters and sons alike, accompanied their fathers and sometimes their mothers to work from an early age. Eight- or nine-year-olds sweeping up the hoist house were not an uncommon sight; occasionally, even a child of four or five might be found helping to carry and stack small rocks. Adolescent girls learned to hammer ore into smaller chunks in preparation for additional milling. At twelve, boys frequently made the switch to working underground, gaining skills that they would eventually bring with them to Michigan. An 1839 report found that 7,000 children worked in the Cornish mines. While the population of underage boys working in their Copper Country counterparts probably never reached the same levels, photographs taken at the Quincy Mining Company in the late 19th century depict a number of small faces.

C&H in 1875 was no different, and Charles Alschbach did not become the youngest worker on the payroll when he accepted his new job at the stamp mill. He appears to have been a general laborer for at least the first few decades: asked in 1894 to describe the nature of his work, he wrote that he “work[ed] at all kind [sic] of jobs” in the company. About a year later, he settled in the mill’s machining department, where he built boilers, and began to earn $52 each month: not a bad wage for the time and place. And he needed the money, too, in light of his growing family responsibilities. Charles had married Anna Opal in 1884, and they welcomed daughters Theresa in 1891 and Irene in 1897.

By 1916, when Rodolphe Agassiz handed him a gold medal and shook his hand, Charles’s life was firmly bound up in the operations of C&H. His home sat on land leased from the company. He paid for it with an income that had steadily increased over the years: by 1913, he earned $78 per month. Through all the tumult of the 1913-1914 strike, Charles remained loyal to the company and walked to the stamp mill in the dead of winter, the heat of summer, and as leaves budded on springtime trees and fell, crimson and gold, from them in autumn. When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, pledging to support the Allied Powers in their fight against Germany and its partners, C&H also joined the fight. The Copper Country mines, wrote Larry Lankton in his seminal Cradle to Grave, reached “their highest peaks ever of production and profitability.” All hands went on deck to help, including Charles Alschbach.

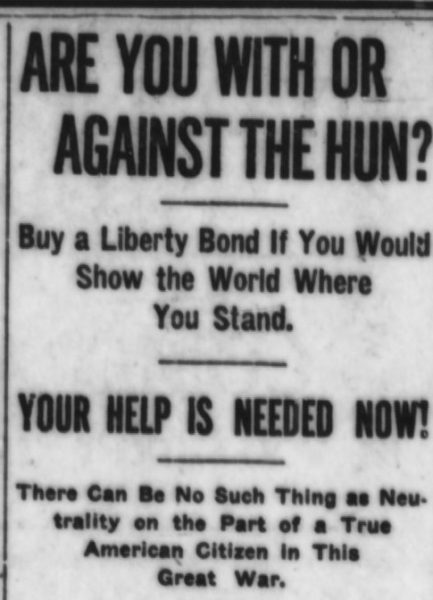

Historically, wars have tended to carry with them two prominent traits: heightened patriotism among the people and a profound need for money on the part of the government. To address the latter, taxes ticked upward nationally, and the federal government began to issue what it called Liberty Bonds, which allowed it to receive loans of money from private individuals on the promise of repayment with interest. The first Liberty Bonds or Liberty Loans, totaling $1.9 billion, rolled out shortly after the declaration of war in April 1917. Three subsequent issuances of bonds followed: $3.8 billion in October 1917, $4.1 billion in April 1918, and a final round of $6.9 billion in September 1918. The bonds sold well by calling upon patriotic fever sweeping the United States–and something else. No one was required to purchase a bond, at least not officially, but failure to do so led to askance looks from neighbors, suspicion from coworkers, and even intimidation from the most passionate supporters of the war effort. Newspaper articles warned Americans that failure to participate in the Liberty Loan scheme and provide funds for military supplies could cost the United States the war. And who could confront the possibility of being conquered by the Germans? Only those who must secretly resent American democracy and pine for the autocratic rule of the Kaiser.

Anti-German sentiment was not new to the United States, but it reached an apex during World War I. How could the people that Americans held responsible for unprecedented carnage in the trenches of Europe successfully integrate into their society? The German neighbor who had run a butcher shop had seemed innocuous before; now, he seemed like he could be a possible spy for the kaiser’s forces, who were themselves butchering the young men of France and the United Kingdom. Now, with American doughboys headed overseas, discomfort with all things German intensified. A town in Michigan that had, for decades, carried the name Berlin shed its moniker in favor of Marne, honoring a battle in which the Allied troops prevailed. Diners sat down not to enjoy sauerkraut or hamburgers but liberty cabbage and liberty steaks. Theodore Roosevelt had cautioned in 1915 that “there is no such thing as a hyphenated American who is a good American. The only man who is a good American is the man who is an American and nothing else.”

Immigrants and native-born Americans of German descent who hesitated to purchase Liberty Bonds–or who spoke German around the dinner table or stood on the corner reading a German-language newspaper as the war waged–seemed suspicious in their loyalties, as far as those who took Roosevelt’s admonition most to heart were concerned. Many German-Americans attempted to prove that they were truly American in Roosevelt’s sense of the term by enlisting in the service, volunteering with the Red Cross, proudly declaring their support of the American Expeditionary Forces, and, of course, participating in the Liberty Loan program whenever new bonds were issued.

Charles Alschbach was a first generation American. George and Caroline Alschbach both immigrated from the small states of Germany to the Copper Country. Although Charles spoke English as his native tongue and had never resided anywhere but the United States, he bore a German surname, and his family attended a German Lutheran church. Perhaps he flew an American flag in his window; perhaps he remained thoroughly ambivalent about the war and its aims. We have no record of his private thoughts. We have only an inference.

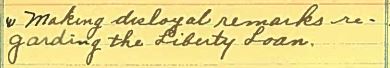

On September 25, 1918, Calumet & Hecla abruptly dismissed Charles Alschbach, Gold Medal Man, from his employment. Forty-three years of association with C&H ended that day. Alschbach never worked for a copper mine again. His cause for dismissal, the only blot noted on an impeccable record:

“Making disloyal remarks regarding the Liberty Loan.”

The last round of Liberty Bonds, the one totaling nearly $7 billion, was poised to be deployed within days of Alschbach’s dismissal. His comments on the matter may have been truly appalling to even an objective observer. On the other hand, they could have been innocuous remarks about how much money the government was spending, or expecting Americans to spend, that aroused deeper criticism because the son of German immigrants spoke them. Regardless, the word that C&H chose to describe Alschbach’s comments–disloyal–carried with it a heavy weight. It cast a pall on his citizenship, his care for his neighbors and friends, his ability to be a true American, his allegiances in the largest fight the country had joined since its birth in 1776. What must a man who had given more than four decades of his life to a single company, let alone resided in the same region since his birth, have thought when he was branded disloyal in any capacity?

The next few years saw dramatic changes in Charles Alschbach’s life. For emotional or financial reasons, or maybe to join his brother Christian, he and his family left Lake Linden. By 1920, they were settled on Waverly Avenue in Detroit, where Charles had found work in an auto factory, most likely Ford. Daughter Theresa became a teacher. The other Alschbach daughter, Irene, and her husband resided with Charles and Anna Alschbach, and the presence of a growing brood of children likely brought joy and comfort to their grandparents, especially when Irene died at a young age.

At 73, Alschbach retired from work. The next two years he spent in failing cardiac health, passing away on September 2, 1935. He was buried in Roseland Park Cemetery in Oakland County, a world away from the mining company that accused him of disloyalty after hailing him one of their Gold Medal Men.

The Library of Congress’s “Shadows of War” and Sara J. Keckeisen’s “Coming of the Night” informed this post.

I cannot imagine working so long for someone and then getting dismissed just “like that” This is not a story that this YOOPER of 65 plus years had heard before.I find these blogs interesting. One wonders just what comes next from the archives

How distressing that must have been for Charles and his family. I can’t imagine there was any ill intent from someone who had a such a strong and proven record for so many years. Such contrast with today’s open commentaries.

Another thoughtful presentation of local history woven with human interest and sensitivity. I look forward to your more of your writings.