Living in the Upper Peninsula has always, to some degree, required Yoopers to know how to make their own fun. When the snow falls to the tune of two or three hundred inches annually, a person either learns to love winter or how to pack up and move. Likewise, the resident of a small town who longs for the attractions of a big city either contents himself with what he can do at home, or he does his best to bring the city home.

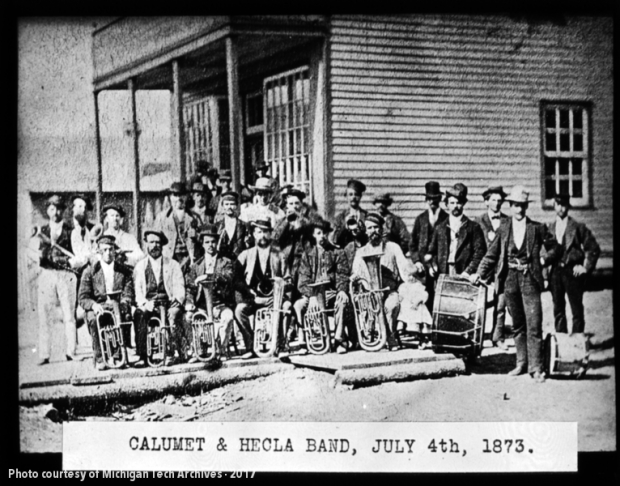

From the early days of industry in the Keweenaw Peninsula, its residents sought to do something of both, combining the entertainments they knew elsewhere with the feel of the region. Mining towns throughout the Copper Country, both large and small, devised their own ways of having fun, which often took the form of creating bands. Copper mines throughout Cornwall, the western region of England from which many early immigrants came, often supported the establishment of a brass band; the band both provided wholesome diversion for residents and promoted the mine. Musical groups began to form in the first few decades of copper mining in Michigan as companies and communities took root. Unsurprisingly, in composition and style, these ensembles reflected the musical traditions of the new arrivals. By 1873, men at Calumet & Hecla had organized into a traditional British brass band, a group dominated by cornets with supplementation by clarinets, horns, and a small percussion section. These days, a cornet might be unfamiliar to many audiences, but the instrument’s mellow tone and bell shape–an appearance something like a modern trumpet–were instantly recognizable to the Cornish people of the early Copper Country. As bands at Calumet and Central Mine, among other places, became more established and increasingly entertained at concerts, dances, and Fourth of July festivities, they contributed to a vibrant cultural life in an industrial world.

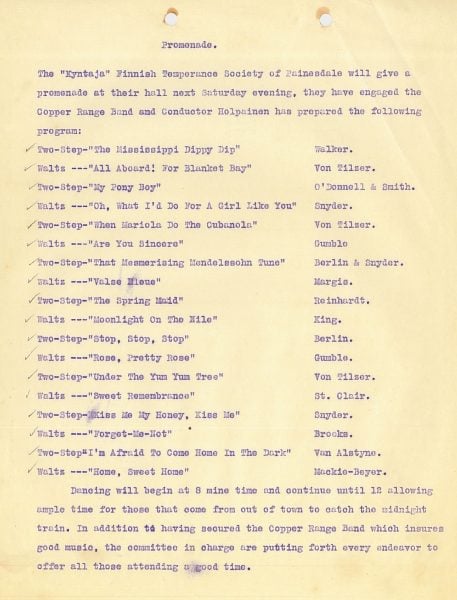

Among the best-documented mining company and community bands of the region was one established by the Copper Range Company, a sizable competitor of C&H with its heart of operations at Painesdale. The band seems to have been formed in 1910, about a decade after the birth of Copper Range. By this point, the ethnic composition of the Keweenaw Peninsula had changed considerably; alongside the English, German, and Irish immigrants of forty years earlier were substantial numbers of new arrivals from Finland, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Italy. The band membership, as recorded by its secretary E.W. Kruka, demonstrated the extent of Finnish settlement along the range: surnames like Ylijoki, Laukka, Hyrkas, and Waara dominated the list. In fact, only two men–Thomas Letcher and Helmut Steinhilb–out of the two dozen musicians did not have obvious Finnish heritage. Despite the change in background, however, the style of the band remained much in line with the traditional British brass form. One of Kruka’s first responsibilities in March 1910 was to place an order for cornets, horns, and trombones, as well as books of solo music for these instruments and drums. Band leader and conductor Charles Holpainen, unsurprisingly, took a prominent role among the cornet section. He, Kruka, and other officers of the band proceeded to lay in a large supply of music for the Copper Range men to learn, attempting to keep their repertoire contemporary, lively, and interesting to their audiences. Throughout the year, Kruka dispatched letter after letter on behalf of the band to suppliers around the Midwest, ordering popular waltzes like Strauss’s “Blue Danube,” rousing tunes with titles like “Swedish Guard March,” and arrangements designed to appeal to the national pride of audiences, such as “Selection of Finnish Melodies.”

The Copper Range Band also sought to bring a touch of professionalism to their performances with the addition of uniforms. Earlier bands had commonly been photographed in good suits and hats, as in the case of the Central Mine ensemble. Men looked nicely-outfitted but not coordinated as a group, given the variations in suit colors and hat styles. For the company’s new band, Kruka placed an order with a tailoring house to equip each man with matching coats and caps. Holpainen’s apparel received extra attention, with “band” embroidered on the hat and “leader” along the coat’s shoulder straps. The uniforms were slow in arriving, even before the special order for Holpainen’s conductor’s gear, and Kruka wrote again to the business, greasing the skids a little with a hint that it would secure uniform orders for his fraternal organization if only the uniforms came through expeditiously. With any luck, they arrived on time for the performance.

Company bands and their members regularly enjoyed particular status in the community in exchange for their work. The leaders experienced this most of all. Calumet & Hecla’s band master, for example, earned $100 monthly, a handsome salary at the time; historian Larry Lankton succinctly described the job of the Quincy Excelsior Band’s director as “cushy.” But even for men who were part of the rank and file, being in the band brought along perks. In response to a letter from John McCarthy asking that “one of the Painesdale bands,” much in demand, come down to Winona for the community’s all-day Fourth of July celebration, Kruka wrote that members of the band “usually get $5 per man for a ‘Fourth of July’ service.” Since McCarthy had outlined a program that would require the musicians to arrive the day before and stay two nights, missing the next day’s work, Kruka drove a harder bargain. To compensate for the lost shifts, he requested an additional $2.50 per man, as well as for Winona to cover the roundtrip train fare. Naturally, the men would be riding the Copper Range Railroad to their destination.

In their regular lives, the Copper Range men drilled into rock walls, hammered iron, and managed inventory. In their musical lives, they played for fraternal organizations, community concerts, and local dances; they provided accompaniment for rallies advocating for Prohibition, entertained groups of socialists, and serenaded conservatives. Music, they say, is universal, and the Copper Range Band illustrated it. Finnish men played German waltzes in British style to American audiences, bringing tastes from over the Atlantic to Michigan to serve a varied people in a remarkable place. What could be more universal than that?