A few weeks ago, Flashback Friday took a look at the first incarnation of the Keweenaw Central Railroad. This rail line filled the many needs of the Copper Country in its industrial heyday: it carried copper, albeit in smaller-than-anticipated volumes, and other local products south to be brought to market, and it ferried pleasure seekers and travelers north into beauty.

The second Keweenaw Central shared the name of its predecessor but only part of its mission. By 1967, when the inaugural train rolled out, the commercial landscape of the Copper Country had changed dramatically. The mines that the original Keweenaw Central served had long since closed. The Quincy Mine, once admiringly hailed as “Old Reliable,” lay dormant. Even its peers, the mighty Copper Range and Calumet & Hecla, found themselves in the last minutes of a long twilight. Both would cease their native copper production within the year, with work continuing only at the more distant chalcocite deposit at White Pine. Mining no longer drove the Copper Country’s economy.

Although even early advertisements for the first Keweenaw Central attempted to entice residents of distant cities to visit the peninsula, the establishment of the second Keweenaw Central reflected the region’s efforts to reinvigorate itself. No commercial freight or commuters rode these rails. This line was intended for tourists and sightseers, with a location and equipment thoughtfully chosen to make their experience memorable.

Four railroad enthusiasts with a creative eye for business were behind the new-old railway. Clint Jones, a native of Milwaukee and graduate of Michigan Tech, served as a president of the company and managed its daily operations. Fred Tonne, his vice president and right-hand man, actively promoted and advertised the vision he shared with Jones. The two were no desk jockeys. Both put in their fair share of time under the cars and engines, maintaining the equipment; Tonne strolled through the passenger cars, greeting guests and performing the duties of conductor, while Jones was known to settle in as engineer for excursions, including the very first one. Louis Keller and Frank Glaisner also contributed their “talents, equipment… and plenty of muscle, too,” in the words of one news piece profiling the railroad, to make the Keweenaw Central a reality. They “felt… the strong desire to preserve it for its historical interest and significance to the Copper Country where it served as a pioneer line.”

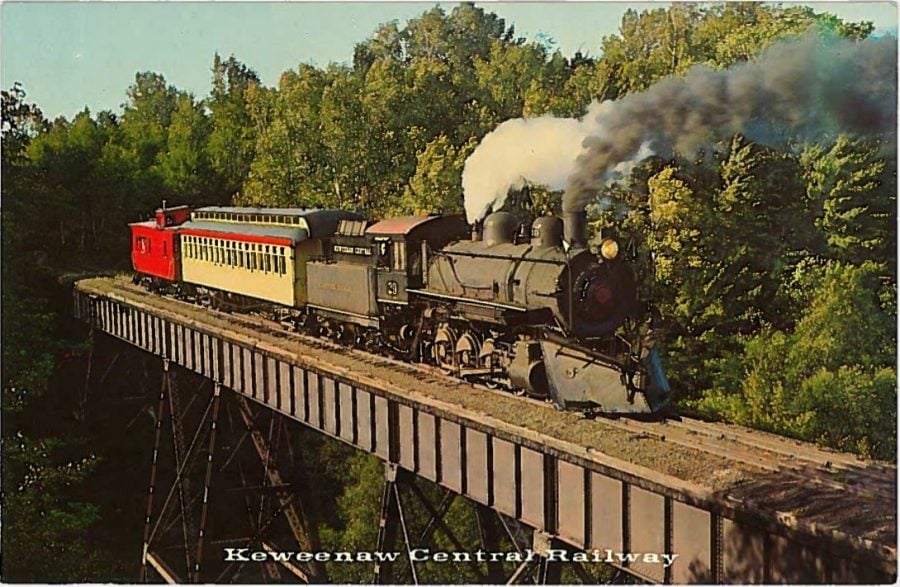

Jones, Tonne, Keller, and Glaisner chose to revive their line as a steam railroad, the only one of its kind in the Upper Peninsula. Out of storage came Copper Range Engine No. 29, a locomotive built in 1907. Copper Range had purchased No. 29 and seven engines like it to support its freight services, gradually transitioning it to passenger duty as industrial demand decreased. By 1953, No. 29 alone survived; all of its sisters had come to sad ends in the scrapyard. With its elegant, classic appearance and a fresh coat of paint, this engine was the perfect choice for Keweenaw Central’s purpose. From its smokestack rose a picturesque plume that seemed to belong to the trains of legend. A wooden passenger coach with open vestibules, Copper Range’s No. 60, completed the charming train.

The Keweenaw Central’s route complemented its scenic equipment. From its ticket office, a converted coach, and home base on Sixth Street north of M-203 in Calumet, No. 29 chugged through Hecla and Albion locations, passing industrial buildings and residences for the workers who had once staffed them. The train wound north to Centennial, then back through Calumet Junction and toward St. Louis, a mine with more hope than copper. It followed the eastern edge of Laurium, skirting the old airport, before entering the most breathtaking part of the journey. The Keweenaw Central line descended down the hill toward Lake Linden, Trap Rock Valley unfolding to the north, Lake Superior glittering where the land dropped away, the Huron Mountains rising on the distant horizon. Bridge No. 30, a wooden trestle situated 120 feet above Douglass Houghton Creek, provided just one memorable example of the dozens of Kodak opportunities along the 13-mile round trip.

Summer and fall emerged as the logical seasons to operate the Keweenaw Central Railway–summer with its verdant vibrancy, autumn with its varicolored splendor, and no need to plow snow from the rails at either time. In 1968, the first train of the year steamed out of Calumet on June 22. Daily runs continued through Labor Day, when more occasional excursions to view the fall colors took over. The various departures throughout the day bore creative names, which often switched when the train reversed directions in Lake Linden: Detroit Express, Northern Michigan Special, Copper Country Limited, North Country Mail. Jones and the other railway operators hoped to capture the feel of the region by reviving these route names, which had once been trains by which local residents could set their watches. Company advertisements emphasized the railway’s ability to capture the “fabulous–historic–mysterious Copper Country.” Aboard the train, passengers of all ages could “find new thrills” or “relive grand memories” unique to riding on a historic steam train, passing over familiar territory or discovering a newborn love. Prefiguring the network of Heritage Sites that would arise decades later with the creation of Keweenaw National Historical Park, Keweenaw Central promotional materials also positioned the railway as part of a larger effort to tell the Copper Country story. They turned a visitor’s attention to other local attractions that would shape his understanding of the region: Fort Wilkins, the Quincy Mine, and the profound beauty of Lake Superior chief among them. The effort hearkened back to the original Keweenaw Central, which had also promoted the organic allure of the peninsula alongside its industrial character.

Unfortunately, despite the best efforts of Jones and company, the second life of the railroad was shorter than its first. As a sightseeing tour, the Keweenaw Central Railway enjoyed its share of popularity, and its fans came from throughout the Great Lakes region for the experience. By 1971, however, it faced pressing difficulties, most notably the imminent abandonment of the Copper Range line with which it connected. The directors made the painful decision to discontinue operations, announcing that the last train would run on Sunday, October 10. Engine No. 29 had been sidelined for boiler repairs a year earlier, so a diesel-electric locomotive claimed the honor of pulling the final consist. Riders descended from Madison, Duluth, Detroit, Minneapolis, and other Midwestern towns to be part of the terminal run, and Jones assumed the role of engineer once again. Charles Sincock, a former vice president of the Copper Range Railroad, also joined the riders.

On October 10, the train slowed and halted in the woods. Passengers ranging from young children to retirees clambered down from the rail cars to pose for a commemorative photograph. “LAST RUN!” read the handwritten poster that Keweenaw Central Railway executives bore. “KEWEENAW CENTRAL RAILWAY, 1906-1918, 1967-1971. THE COPPER COUNTRY ROUTE. UPPER MICHIGAN’S ONLY PASSENGER TRAIN. GOODBYE FOREVER TO OUR FRIENDS. R.I.P. OCT. 10, 1971. FINIS.”

Within two years, the tracks that the Keweenaw Central traveled would be torn up, leaving the line to return to nature. Engine No. 29 was parked at the Quincy smelter, awaiting the day when it could be brought to a museum. The days of rail in the Copper Country had come to a quiet end.

Beautifully written and brings back great memories for me growing up by the tracks in Hancock. The train going by was a reliable part of every day and one of the three most exciting sounds of travel–the train whistle. I appreciate the memories of not only the train, but of the mines and mining in our Copper Country. Excellent photo for that touch of nostalgia. I would love to take a train trip!

ALLLL aboard as they might say, the stories of the trains and mines and people of hose days can evoke a “lump in the throat” moment even for an old Yooper like me! I appreciate that someone keeps memories of those days alive and available for us to read about them. Nice history lesson ………………I bet there was no conductor walking on that train scolding passengers saying “you gotta have a ticket to ride the train”