Joseph Riippa died instantly.

His passing was the sort of event that people rightly label one in a million: he was struck by lightning. Yet the place and time where the lightning found him were entirely in keeping with the character of a young man who had devoted himself to ministry and his immigrant roots with a full heart. When he died in Hancock on August 28, 1896, he did so just as he had lived: active, thoughtful, and surrounded by Finns to the last.

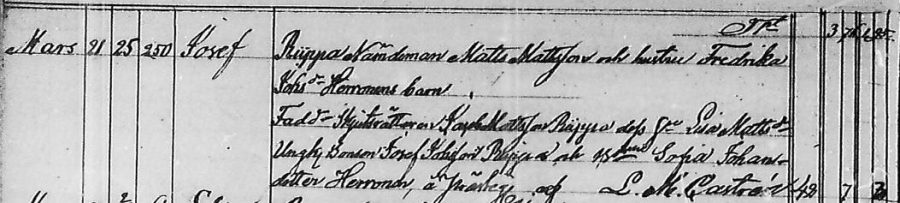

On March 21, 1868, a son arrived in the Kälviä, Finland, home of local judge Matti Riippa, his wife Fredrika, and several siblings. Four days later, the boy was christened Josef, according to parish records then maintained in Swedish. Among the Finnish speakers by whom he was surrounded, the newest Riippa would generally be called Jooseppi.

Jooseppi was born on the eve of great changes for Finland. Finns had been journeying to the New World since the mid-17th century, when a group of them ventured out as settlers to colonize Delaware for Sweden. As Armas K.E. Holmio, writing his seminal history of Michigan Finns, put it, despite the name, New Sweden was obviously “more Finnish in nationality than Swedish. This fact has been an embarrassment to some Swedish historians.” In the mid-19th century, however, this emigration began to accelerate dramatically. Holmio tallied some 500 emigrants from Finland between 1871 and 1880, less than one percent of the people who left Sweden or Norway in that same period. Between 1881 and 1890, the number of emigrants more than quintupled to 2,700. In the 1890s came a genuine explosion: 59,100 Finns took a last look at their homeland and set out for foreign lands.

Finnish writers to this point had looked on emigration as an unusual occurrence and one “that was not a credit to the country,” as Holmio said. Literature and song presented Finland as a place of exceptional beauty and potential, imploring Finnish youth to remain where they were. As the 19th century wore on, however, both young and old found life in Finland increasingly difficult. The country had developed a major tar industry, especially in the region around Kälviä, for sealing wooden sailing vessels, and the emergence of steel steamships that needed no tar devastated the area. Finnish shipyards that could not transition to steamship production ceased operations, putting countless laborers out of work and sending shockwaves through the local economy. Crop failure in the years just before Jooseppi’s birth, increased subdivision of small farms, and limited resources to acquire costly land strained the ability of Finns to feed their families. Poverty and all its consequences became constant companions.

Desperate for hope, the Finnish people began to look abroad. Some sought opportunity in the copper mines of northern Norway. There, and in Finland itself, they began to hear the promises of America circulated in their communities. Holmio noted that the reports from abroad were often “highly exaggerated… a former shepherd boy might tell of being a superintendent of a large lumber camp where he was, in reality, the janitor of the bunkhouse and the cook’s helper.” Stories that came home “often emphasized the bright side of life and remained silent on its negative aspects.” Money earned in America arrived with the letters, heightening the appeal. Passenger steamship lines picked up on the increasing allure of America and phrased their sales pitches and advertisements to emphasize glamor, adventure, and a better life overseas. Agents in American towns where a few Finnish people had already settled–including those who had been drawn from Norwegian mines to Michigan ones–also advertised locally, pitching low prices and easy arrangements for immigrants seeking to bring their loved ones to the New World. Finns at home and in the United States began to talk among themselves. America was a long way from Finland, and Finland would always call to them. Yet they could not provide for themselves in Finland, and dying at home appealed to fewer of them than living abroad did. Even if they would not become rich beyond their dreams, the work would be steady. Laboring in this industry or that one overseas might provide enough money to buy a farm–if not in Finland, where land was expensive, then in America, which seemed poised to be the breadbasket of the world.

Jooseppi’s family soon became part of this story. In 1872, when his youngest brother was just four, seventeen-year-old Jaakko Riippa set out across the Atlantic, leaving behind the economic troubles of Kälviä. Matti and Fredrika, along with their minor children, continued to reside in the parish for another decade, presenting annually for the catechetical examinations that Lutheran ministers were required to give their congregations. After 1882, however, the family’s entries in these records ceased. Driven perhaps by stories that crossed the ocean back to Kälviä or by the untenable conditions at home, they had decided to cast in their lot with Jaakko and their countrymen in the United States. They became American Finns, and Jooseppi became known as Joseph among English speakers.

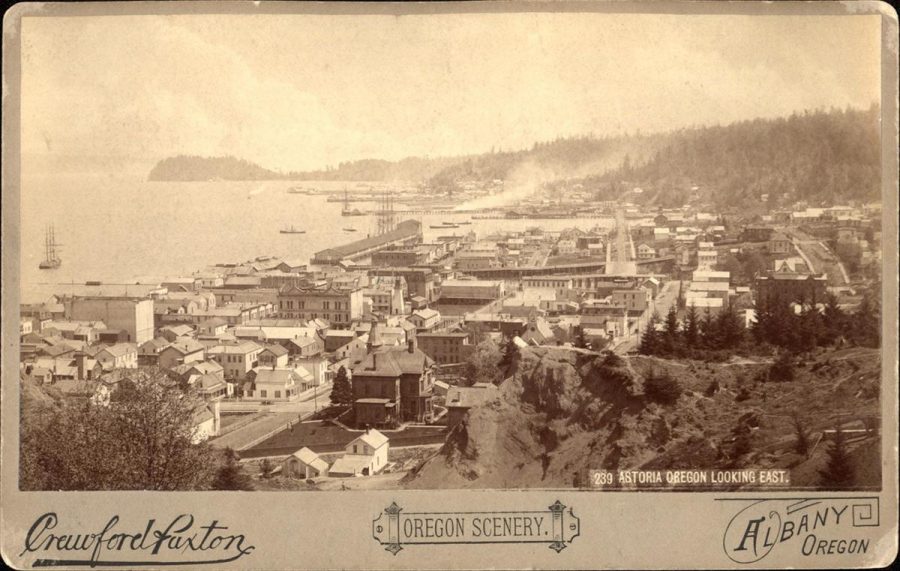

A tragic irony of Joseph’s eventual death was that his family did not settle in Michigan. They chose another area popular with Finns and Swedes alike, taking up residence in Astoria, Oregon. In this promising port city on the Pacific coast, where the Columbia River emptied into the ocean, Joseph grew from fourteen-year-old boy to thoughtful young man. In an era when many immigrants, including some of Joseph’s own brothers, began to change their surnames to adopt personas that seemed more American, Joseph remained steadfastly a Riippa. His ties to Finland felt as strong as they had the day the country faded into the ocean mists behind Joseph’s ship. Stirred by bittersweet remembrance, he sat down and penned a ballad in his native tongue about the land he loved. The piece spoke of sylvan glades, Joseph’s first memories of hearing birds singing in groves, Fredrika laying her son to sleep in his cradle, Joseph running after Matti’s footsteps, the richness of joy in knowing that his family’s roots ran deep there. He titled the ballad “Kotimaani ompi Suomi”: “Finland is My Home.”

In writing “Kotimaani ompi Suomi,” Joseph also spoke of a deepening religious conviction. In Finland, he said, he first felt the love of God, and he prayed that the country would always be free. The roots of his vocation to the ministry had been fostered in Europe, but they would come to fruition in North America. Presumably scrimping and saving to make ends meet, Joseph managed to enroll in Augustana College, a Swedish Lutheran institution located in Rock Island, Illinois. There he studied “music and churchmanship and… prepare[d] for the ministry,” wrote E. Olaf Rankinen in a 1982 Daily Mining Gazette retrospective on Joseph’s death. When the college recessed each summer, he taught in Bible schools, furthering his ministerial abilities. “He yearned to study in Finland,” said Rankinen, “but apparently finances prevented overseas travel.”

From Augustana, Joseph went back to Astoria for a time. Now in his twenties, he supplemented what he could earn from any church work by taking various clerking positions in town. Many years later, Oregonians who had been children when Joseph taught their Sunday schools and summer programs in the 1890s remembered learning “Kotimaani ompi Suomi” from him. In Astoria, he met or was reunited with Hilma Lantto, a young immigrant from Tornio, Finland. The two fell in love and were married on November 26, 1892. Just under a year later, their only child, Wainard (Waino), was born.

The ministry continued to call to Joseph, who had not yet been ordained a Lutheran minister, and developments in the Midwest piqued his interest. In 1890, the Suomi Synod–a Finnish branch of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in the United States–was established in Calumet. Like Joseph, the leaders of the new Suomi Synod emphasized the importance of the Lutheran faith and their Finnish heritage. It was a perfect match for the young aspiring minister, and he and his wife soon decided to relocate near synod headquarters. They arrived in Hancock in 1895, with the plan that Joseph would assist the pastor at the local Finnish Evangelical Lutheran church and continue his religious training in preparation for full-time ministry.

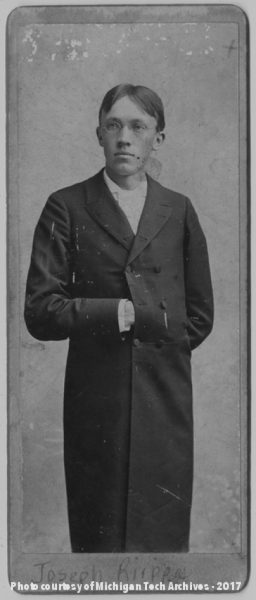

Joseph made an impression on his new neighbors and coworkers immediately, becoming popular among the Suomi Synod administrators and the congregation of his new church. Musical by nature–as his ballad showed–he led a variety of choirs and demonstrated himself to be a reliable, faithful man. Perhaps it surprised him, however, when synod leaders approached him with a new proposition. They had been seeking since the establishment of the Suomi Synod to create a college like Joseph’s alma mater, Augustana, and had decided after much consideration to place it in Hancock. Joseph was significantly asked to serve as a member of the lay board (council); he would be charged with tending to business matters, as well as working with synod leaders to resolve issues of concern to the whole college. He accepted the call and attended his first meeting of council and synod on July 4, 1896. “Far-reaching decisions were made at this meeting,” said Armas Holmio. For Joseph Riippa, the most significant came when he was chosen as one of the three first instructors at the college. Suomi College would begin operations in rented quarters in West Hancock, following a dedicatory worship service at Joseph’s church on September 8.

As Suomi’s opening drew near, Joseph remained busily engaged in his typical program of providing religious education to Hancock’s Finnish children. On Friday, August 28, his fifty young pupils gathered as usual at the Lutheran church for classes. The weather that day was foreboding, not entirely unusual on a summer day near a lake so large that it churns squalls into gales. Clouds gathered on the horizon, and the air seemed electric. Joseph looked out at the sky and determined that something more menacing than a simple thunderstorm was about to descend on Hancock. He dismissed the children early, hoping they could hurry home before the worst weather arrived. Only three of the youngsters remained at the church at 3:30pm, helping to sweep up and tidy alongside the aspiring pastor.

Then came the flash.

The Copper Country Evening News declared that the lightning bolt was strong enough to be felt all over Houghton County. It struck the spire of the Lutheran Church with a mighty clap and ripped down through its roof and stovepipe, seeking the ground. “The spire itself is a complete wreck, being literally smashed into kindling wood and scattered for blocks around,” the paper said a day after the storm. “The ceiling in the front part of the church looks as if a gatling gun had been trained on it, it is so full of holes. The plastering was so badly shattered that the dust enveloped the whole structure and it was thought for a time that it was on fire.” Firemen were dispatched to the scene and found no blaze–but one tragic victim.

Joseph had been standing between the pews in the church when the bolt struck. Ten feet from where he stood, the lightning punched a sizable hole in the floor in its pursuit of ground. The current enveloped him, leaving a black mark on his head two inches wide, and casting him face first to the ground. He was dead by the time he fell.

Hilda Riippa decided immediately to bring her husband’s body to Astoria for burial. She, two-year-old Wainard, and Victor Burman–who was to have served alongside Joseph as a Suomi instructor–departed for Oregon within a day of the lightning strike. There, she would lay Joseph to rest, seek comfort in the arms of her family and, some years later, remarry. Wainard would grow up, serve in World War I, gain a degree in engineering, and eventually die in California, his home of thirty years. Suomi College would grow to maturity and mark its 125th birthday in 2021. And throughout the Finnish communities of the United States, and across the ocean in Finland, generations of Finns would learn “Kotimaani ompi Suomi,” hearing in the poetry the longing to return to his native country that Joseph Riippa took with him to his grave:

“My homeland is Finland,

Finland, the dear land of my birth.”

Armas K.E. Holmio’s “History of the Finns in Michigan,” E. Olaf Rankinen’s article ‘Death marred opening of Suomi,” and a variety of primary sources informed this post. Despite his name, Joseph Riippa is no relation to the author!

Holy Wah great balls o fire