To this day, organizations fielding questions about Copper Country tourist attractions receive calls from people wanting to know, “Is Arcadian still open?”

Visitors to our Keweenaw Peninsula often seek to immerse themselves in the industry that made our area famous. For many of them, this takes the form of a mine tour. Underground, with craggy ceilings hanging overhead and paths roughly hewn from hard rock leading the way, today they walk in the steps of copper miners who worked at Quincy, Delaware, and Adventure. For tourists and locals alike in the middle of the 20th century, however, a different mine would have been an essential stop for such a tour. The Arcadian Mine was never an industrial success, but its second life sparked the imagination of countless visitors over the decades.

Long before it became a tourist destination, Arcadian was not truly Arcadian. It began its life as a series of smaller mines hoping to strike a motherlode, as the nearby Quincy Mine had done. After a decade of struggles, Quincy discovered the wealthy Pewabic Lode in 1858 and transformed itself into “Old Reliable,” a mine that paid annual dividends for nearly sixty years. Other prospectors scrambled over the land in Quincy’s shadow, buying up plots that seemed promising in the early 1860s. Among them were the first company to bear the Arcadian name and ventures by the names of Douglass, Edwards, Highland, St. Mary’s, and Concord. Horace Stevens, whose Copper Handbook served as the core text of copper mining, calculated that these mines produced 650 tons of refined copper over their troubled existence. Like many endeavors trying to prove themselves next to a bigger competitor, most of these mines fizzled quickly, leaving behind poorrock piles and abandoned shafts.

New, more efficient, and more productive technologies developed in the decades that followed. The world seemed bursting with industrial promise to the investors and inventors of the late Gilded Age. Quincy and Calumet & Hecla, its rival to the north, produced copper at rates that turned heads across America. One such head was particularly famous. Standard Oil, that company whose name was a byword for corporate wealth, announced to the New York Times in 1898 that it would invest in a resurrected Arcadian, having been “thoroughly convinced of its richness” by preliminary exploration. Standard’s Arcadian–consisting of amalgamated property from the six aforementioned mines–set about reopening vigorously. “Work was begun on a scale never before seen at any new mine in this field,” Stevens said. Its investors poured over $2.5 million into the property at the outset, purchasing construction materials and supplies that arrived in Hancock by every conveyance imaginable. “Great shafts were started into the bowels of the earth at a half dozen points, and as rapidly as depth was gained drifts were run both north and south on every level,” Stevens marveled. In a single month, Arcadian’s workers opened some 1,800 feet, “a record that has never been duplicated by any mine but the Calumet & Hecla.” Shafthouses, auxiliary buildings, and homes arose in a matter of months. Wrote one newspaperman later, “The town… seemed to spring forth from the wand of Houdini.” The workforce did, too. At its peak, one thousand people worked for Arcadian, and many lived in its eponymous housing location. There, two parallel streets offered “houses of exceptionally fine structure… with a view toward ample room and space,” nestled above the scenic spread of Portage Lake. Stocks rose, and hopes rose higher still.

But even Rockefeller’s riches could not save Arcadian. “It is to be regretted,” said Stevens wistfully, “that the expenditure of such a vast amount of men and the elaborate preparations made for production upon a large scale have not been rewarded by the opening of a better mine.” Arcadian’s copper was exceedingly poor: less than one percent of the rock it extracted could be milled. Within two years, it became patently obvious that the output from Arcadian could barely keep its single stamp mill occupied, let alone the second mill that management had planned to build. Miners opened seven shafts on the amygdaloid lode upon which Arcadian sat; in 1902, just four years after the construction boom, only two remained in operation. Equipment shops, intricately planned and thoroughly supplied, sat idle. Eventually, even the most hopeful investors had to concede defeat. Deeply in debt and with little to show for expenses that mounted as high as $7 million, Arcadian sold out to hungry competitors: the hoists and other machinery to Copper Range, the mill to C&H, tracts of land to Quincy.

For many mines, this would have been the end of the story. Not for Arcadian. Two additional efforts to extract copper in 1909 and the 1920s amounted to little–but then came Ralph Paoli. As a young man, he worked at Arcadian and, like Standard Oil, became convinced that mining engineers had overlooked the mine’s best offerings. When Arcadian closed, Paoli went into business and attained success as a wholesale fruit merchant. The mine, and his conviction that it still had much to offer, never left his mind. In the late 1930s, he decided to make a go of it. Following the advice of a technical advisor from Michigan Tech, he had his private mining crew start a new adit–a horizontal opening–into the hillside near Ripley, a mile from the older Arcadian diggings. Ralph Paoli died in 1942 without seeing his dreams realized: his crew had tunneled into the hill without striking paydirt. His vision for Arcadian led directly, however, to the mine’s final and most famous incarnation.

The first tourists walked into Arcadian in 1950, traversing Paoli’s adit. Under the management of Abel Matero and Louis Koepel, the new Arcadian Copper Mine Tours emphasized the authenticity of the experience. Although anyone raised in the Copper Country would understand the basic vocabulary of mining and the patterns of a mining economy, only underground workers or mining engineers in training tended to know what it was like to set foot in a mine. Arcadian promised to change that. “Tourists [are] finally able to see the actual workings of a native copper mine and become acquainted with the geology, mining methods and the mining history of the first largest copper mining development in the United States,” said an Arcadian press release. Its operators promised a demonstration of workings identical to those in more typical shaft mines. To further underscore the authenticity of the mine, advertisements pointed out that the mine was “under the jurisdiction of the Houghton County Mine Inspector,” just like the remaining C&H or Copper Range mines.

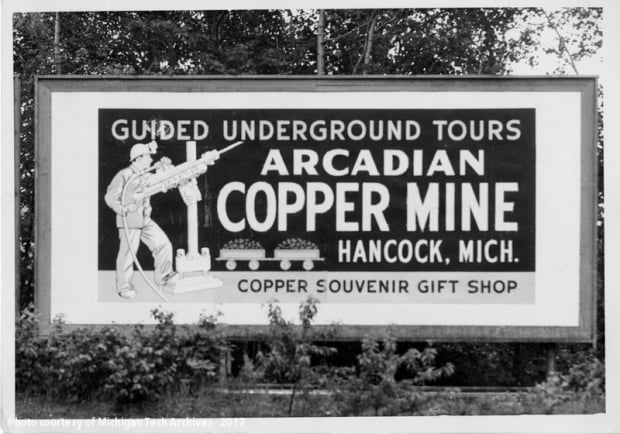

There was something for everyone at Arcadian. For the rock hound, the tour offered “geological wonders created eons ago.” For those fascinated by industrial development, Arcadian provided the chance to “see awe inspiring, man made workings deep inside the earth.” Historians could “revel in the air of an exciting, romantic past,” when striking riches seemed within Arcadian’s reach but fate intervened. Last but not least, for those wanting to take home a reminder of their tour, Arcadian housed a convenient gift shop featuring “copper souvenirs, jewelry, [and] rock specimens.”

An adult visitor choosing to take the tour in 1953 paid $1.25 for himself; his children under 16 came along for only 40 cents each, tax included. In those days, tours began on May 15 for the summer season and continued through September 15. Later seasons, capitalizing on the heightened popularity of fall colors, shifted the calendar to include October. During the peak months of July and August, Arcadian even offered Sunday tours. The mine opened bright and early, at 8am (10am on Sundays), and continued offering tours through 5pm daily. A 1985 Daily Mining Gazette story on Arcadian, describing its tours as “a must” that provided “the thrill of experiencing firsthand an adventure in a genuine underground mine,” said that a tour consisted of 12-17 people. Rarely did an arriving guest have to wait longer than 20 minutes to begin their journey into Arcadian.

An Arcadian tour guide handed each visitor a warm jacket as they prepared to head into the mine: it was always chilly underground. With everyone bundled up, the guide led his intrepid group 1,500 feet into the adit, which sat 425 feet below the surface of Quincy Hill. Electric lights brightened the path, leveled to accommodate both able-bodied participants and those in wheelchairs. At appropriate intervals, the Arcadian employee stopped to point out crosscuts, drifts, stopes, and winzes and to explain their purpose. In a testament to Ralph Paoli’s dream, the guide occasionally produced a metal detector and allowed its beeping to show that copper resided in Arcadian still. Visitors emerged blinking into the Keweenaw sunshine, marveling at their underground expedition.

At its peak, 20,000 people took the Arcadian tour in a summer, with the average gate count totalling around 15,000 annual guests. Locals visited Arcadian in significant numbers, and tourists from the Lower Peninsula, Illinois, and Ohio filled the remaining slots. The opening of the Mackinac Bridge on November 1, 1957 proved an astonishing boon for Arcadian. With downstaters no longer required to wait for a car ferry or drive the long way around Lake Michigan, the Upper Peninsula was more accessible and alluring than ever. People motored north from the Motor City and trekked up from Grand Rapids, and Arcadian’s billboards beckoned them to Hancock. Hilma Erickson, a long-time manager of the gift shop, recalled that 1,000 travelers took the Arcadian tour in a single 1958 summer day.

The revived Arcadian enjoyed a much longer and more fruitful life than its predecessor, but its sunset eventually arrived, as all sunsets do. Management of the mine was turned over to the Quincy Mine Hoist Association in about 1987, and Arcadian’s tours came to an end. Their spirit of discovery and many of their practices continue at the Copper Country mines today open to the public. All three–Delaware, Adventure, and Quincy–are members of the Keweenaw National Historical Park network of Heritage Sites, and all share Arcadian’s fundamental belief: the Copper Country’s past is exciting, worth preserving, and everywhere around us.

It is a very exciting past. Thank you for highlighting this with your well informed insights!

Sounds like an interesting time under the brow of the hill. I was a kid living here then, but missed out on seeing this interesting piece of history I am glad somebody remembers. Thanks to the archives