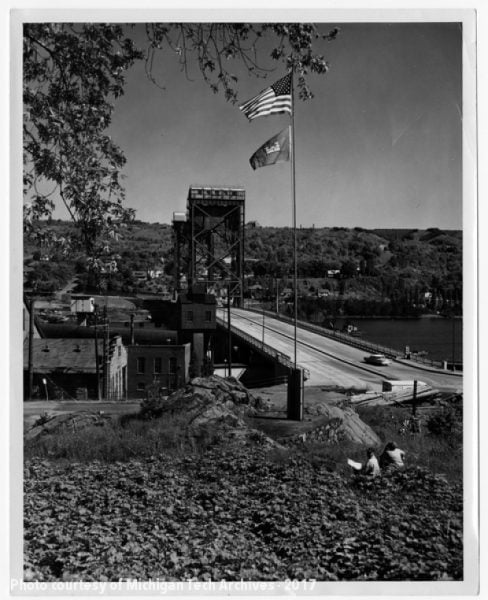

Cross the Portage Lake Lift Bridge, northbound or southbound, or take a walk along the canal in Houghton, and you can’t help but notice it. The Jacobsville sandstone building standing on the Houghton end of the bridge has greeted passersby for well over a hundred years, serving an impressive array of purposes in its century of life.

The last decades of the nineteenth century could be fairly called an electric age. With a series of inventors, not least among them Thomas Edison, making strides in electricity that could never have been fathomed a century before, the Copper Country flourished. Electricity required a conductor, and few could do better than copper. City after city across America lit up, added streetcars, and found other ways to harness electricity for their benefit, all on the backs of Michigan products. Naturally, the Copper Country joined in quickly. James Dee established an electrical plant at the Portage Lake Foundry in 1886, attracting the eager fascination of area newspapers. “Either Houghton or Hancock can be lighted (and you will not require a lantern to find the light either) at a cost little if any exceeding the present rate,” wrote one in January of that year. “The electric is certainly the ‘light of the future’ as well as the present and Mr. Dee is deserving of heaty support from the Village and citizens for the push.” Development proceeded slowly but with great excitement. On March 31, 1887, the electric light system was declared to be in full operation across the two towns, and the proliferation of lights throughout them in the months to follow received extensive news coverage.

Clearly, electricity was in the Copper Country to stay. In October 1887, an enterprise called the Peninsula Electric Light and Power Company formed to transfer the business of electricity from Dee’s hands to corporate ones. Dee assumed a leadership role as the company grew and placed outposts in Lake Linden, Baraga, and elsewhere. Meanwhile, back on Portage Lake, new dynamos (electric generators) bolstered the Peninsula company’s ability to supply electricity to the area, but the need for an expanded plant soon became obvious. In September 1890, it was reported that “work on the new electric light plant has been commenced and now is employing a number of men on the ground excavating for the foundation. The buildings will be immediately west of Van Orden’s lime kiln in West Houghton and on the lake shore… [and] will be constructed of entry sandstone.”

Forever afterward, this new edifice would be widely called “the powerhouse.”

When the powerhouse opened in 1891, it was immediately bustling. Freighters carried coal through the canal and deposited it at Van Orden’s docks for the hungry Peninsula company to devour. An engine of at least 250 horsepower, boilers, dynamos, and other accessories kept Houghton and Hancock glowing brightly. All were housed in a structure agreed to be handsome, with its foundation of Marquette sandstone, its finish of Jacobsville sandstone, its large windows, and its corrugated iron roof. Various expansions to and improvements the facility followed over the coming decade, and conversation quickly turned to the prospect of operating an electric streetcar from the powerhouse. In time, the Houghton County Traction Company would fulfill this dream.

In 1902, the Peninsula company became part of the Houghton County Electric Light Company. Until 1930, when hydroelectric dams in Ontonagon and Baraga counties opened, the Houghton powerhouse remained the Upper Peninsula’s largest generator of residential electricity. In June 1947, the Houghton County Electric Light Company consolidated with the Iron Range Light and Power Company, the Copper District Power Company, and the Houghton County Traction Company to form today’s Upper Peninsula Power Company (UPPCO). UPPCO kept the faithful powerhouse in operation for another decade before changing it to a switching station. By 1965, the switching station closed, as well. For the first time in seventy-five years, the building stood quiet.

But it would not be idle for long. Shortly thereafter, the powerhouse took a turn from industrial to social. Copper Country teenagers longed for a place to hang out with their friends, a place that would serve them as well on stormy days as it did on fair ones. The idea met the approval of local religious leaders and other community members invested in area teens. Hancock youth had already formed a group, the Hancock Teen Center, that hosted dances in one of the town’s parking lots, but everyone felt that more was possible, that a dedicated gathering place would be best. At a meeting, someone proposed the winning idea: why not the old powerhouse? UPPCO was open to the idea, and young people from the Hancock Teen Center board toured the space with 4-H leader Elvin Hepker. “They thought it showed great possibilities,” Hepker said when interviewed by the Daily Mining Gazette.

To make the new teen center a reality, Copper Country youth needed to band together. The Hancock group dissolved and reformed with Houghton peers as the Houghton-Hancock Youth Organization, assisted by an adult advisory board. The organization’s leadership discussed potential renovation plans and settled on a favorite, which they presented to UPPCO for approval. Bosses at the power company gave their blessing and removed the remaining electrical equipment. Soon after, they deeded the property to the Copper Country Chamber of Commerce to hold in trust for the teens.

The Houghton-Hancock Youth Organization worked hard to raise money for powerhouse renovations. In December 1967, the Gazette reported that their plans would require about $10,000 to complete. The estimated cost came mostly from supplies; “the youths and interested adults” planned to donate as much labor as possible. Through this collaboration of physical work and fundraising, the teen center was ready for opening within a year. Featuring fluorescent and colored lights, hardwood floors, a ten-foot ceiling, wood paneling in vogue at the time, a lounge, and a snack bar, it made for an inviting space for regular Friday and Saturday dances. Boy Scout and Girl Scout troops, 4-H clubs, and other community youth groups also had an open invitation to use the powerhouse as a gathering place.

While the teen center quickly became popular with its target audience, unfortunately financial difficulties quickly came calling. The cost of upkeep and operations for the old building took a toll and made running in the black nearly impossible. By 1974, the teen center was forced to close its doors, and youth activities shifted to the Dee Stadium ballroom for the next few years. Meanwhile, the old powerhouse passed through various hands as it gradually fell into disrepair.

One developer proposed to transform it into a hotel, an idea that never gained traction. In the 1980s, contractor Thomas Moyle, chief of a local construction firm, purchased the building and held onto it for the next decade. When spring arrived in 1998, Moyle’s employees began a concerted renovation of the exterior. The decision pleased Houghton leaders; the city manager had expressed “some concerns about… the building” and its deteriorating condition. Crews swept up bricks and chunks of sandstone that had crumbled around the powerhouse; they repaired mortar joints around the sandstone remaining in the building, a process called tuckpointing, to minimize further disintegration. At the time, Moyle said, he had no plans to do further work on the interior. The building would remain as it otherwise was until someone stepped forward to lease or purchase it.

The right match came along just a few years later. Michigan Tech saw the old powerhouse as the perfect home for its Enterprise SmartZone, an incubator for high-tech businesses like those its graduates produced. Here, startups just getting off the ground could set up their first professional spaces and try to attract attention. The Local Development Finance Authority, a financial wing of the SmartZone, purchased the building from Moyle for $374,000. By February 2003, about half of the $450,000 renovations necessary to make 7,500 square feet of the powerhouse into offices and cubicles were complete; Michigan Tech officials and the first businesses moved in that June. Early residents included GS Engineering, whose employees expressed enthusiasm about the beautiful view from their new workspaces.

Additional renovations and improvements to the powerhouse-turned-SmartZone continued over the next five years. More square footage was tidied up, creating better bathrooms, dedicated conference rooms, and better access to large windows that allowed sunlight to stream in. In the nearly two decades since, the building has demonstrated once again that it has staying power, that, like the Copper Country, it is endlessly versatile and always prepared for reinvention.

What a trip the old Powerhouse Teen Center was!! I remember this time when I …………well no need to say more. It was a vibrant place when it operated and I was there lot of fun it was. Thanks for writing I liked the story/history.