August evenings in the Copper Country tend to be warm and relaxing, the type of atmosphere that invites people to sit on porches and savor the summer. For Calumet on August 13, 1983, evening peace would be impossible as a century of history vanished into the flames.

In 1868, the place later called Calumet was an infant town–raw, unpolished, smelling of smoke and fresh-sawed boards. The twin mining companies that would eventually become the great Calumet & Hecla had just begun to show flickers of promise. Workers arrived to try their luck with the young mines, and the settlement grew.

Recognizing that Calumet’s Catholics had spiritual needs along with their material ones, Father Edward Jacker began to journey up from Hancock as early as 1865, when the town was newly born. Father Jacker was, like many of those to whom he would minister, an immigrant to Upper Michigan from Germany. He had come to the United States to pursue a priestly vocation with the Benedictine religious order before hearing that a bishop in a distant northern state had called for missionary priests to serve his people. Jacker hurried to answer the call and in 1855 was ordained by Bishop Frederic Baraga, who no doubt received him with great joy. In addition to filling in for Bishop Baraga on occasion, Father Jacker’s early assignments were Houghton and Hancock, which positioned him well to learn of Calumet’s sacramental needs.

Catholics gathered for the first Masses offered at Calumet, in about 1865, at a private home. Soon, however, attendance exceeded capacity. Father Jacker and his fledgling flock relocated to a mine carpenter’s shop, but the need for a permanent house of worship was only too apparent. With the blessing of Bishop Baraga’s successor, Ignatius Mrak, the priest in 1868 established his residence at Calumet and turned his attention to the business of establishing a parish.

Like most buildings that arose in young mining towns, the earliest Sacred Heart of Jesus church was a wood-frame structure constructed on land leased from the mine. According to a Daily Mining Gazette article issued on the parish’s centenary in 1968, this first church stood 40 feet by 90 feet and enjoyed a location in Hecla location, on the southeast side of town. All of Calumet’s Catholics–primarily of Irish and German extraction in the early days–worshiped there initially under the pastoral care of Father Jacker. After he was called away, a series of other priests, appointed by the diocesan bishop, arrived to serve the expanding parish. In about 1890, however, an order of Franciscan priests based in Cincinnati accepted pastoral responsibility for Sacred Heart, a caring role they would fill for decades to come.

Like Calumet, Sacred Heart soon burst at the seams with new arrivals. C&H was flourishing, and the township in which it operated grew from 3,182 people in 1870 to over 12,000 residents in 1890. By 1900, the population would reach 25,991 individuals, many of them Catholics. Sacred Heart’s modestly-sized building could no longer serve the entire Catholic flock of Calumet, who now spoke a variety of tongues far beyond those of Sacred Heart’s initial parishioners. Some formed their own ethnic parishes: St. Anthony of Padua for the Polish, St. Joseph for the Slovenians, St. John the Baptist for Croatians, St. Mary (or Santa Maria) for Italians, St. Anne (St. Louis) for French Canadians.

Meanwhile, Sacred Heart broke ground for a new, larger building adjacent to its current one. Calumet was no longer a raw and new town: it had established itself and put down roots. The second Sacred Heart Church reflected this change, transitioning from wooden construction to Jacobsville sandstone. With a length of some 160 feet along Rockland Street and an additional chapel near the rear of the building, not to mention a towering steeple and high-pitched roof, it was an impressive edifice and a good complement to the stone rectory next door. Inside, soaring beams and an elaborately beautiful altar drew the thoughts of Catholics toward heaven. Bishop John Vertin, a native of Slovenia, dedicated the church on October 16, 1898.

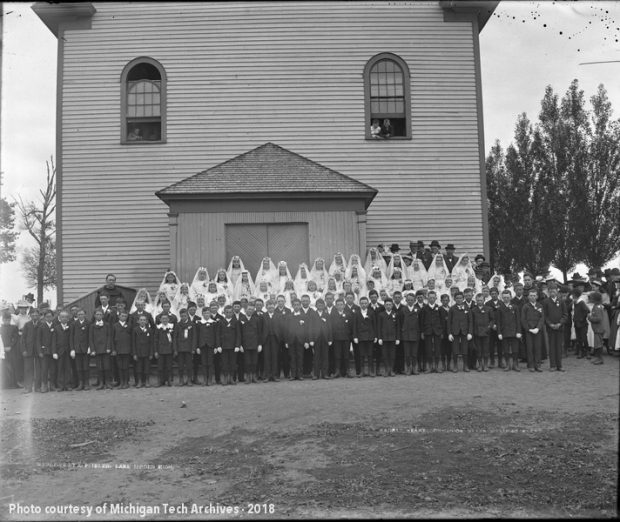

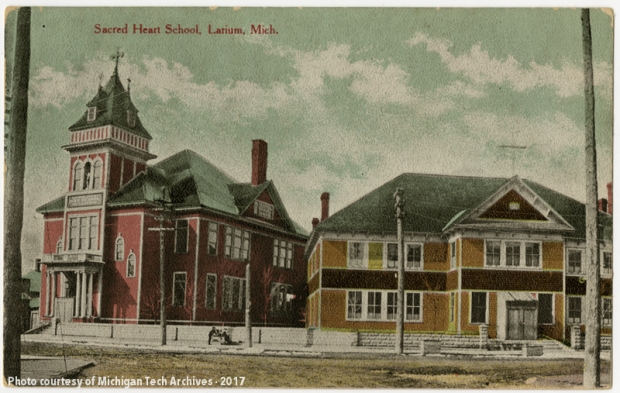

Blessed with a new and expanded building, the ministry of Sacred Heart continued to grow. In 1905, the Franciscan Fathers received sacramental responsibility for the Catholic mission churches of the Keweenaw–places like Copper Harbor and Eagle River–and gladly assumed their duties. Meanwhile, In 1891, the parish had established a grammar school at the corner of Lake Linden Avenue and Calumet Street in Laurium. From the first day of instruction, over 300 pupils were enrolled, showing the appeal of parochial schools to Calumet parents; under the leadership of first Father Peter Welling and then Father Sigismund Pirron, Sacred Heart added a high school program in 1893 and a separate building for these students in 1902. A library and an auditorium/gymnasium, seating some 600 people, eventually rounded out the facilities. Scholars received instruction in academics and faith from the Milwaukee-based School Sisters of Notre Dame, who resided in an adjacent convent. The student population peaked at some 800 enrollees, whose parents paid a modest tuition: in 1918, Sacred Heart parishioners were charged 25 cents per child per month, while those from outside the parish contributed 75 cents monthly to enroll each child. A burgeoning parish fostering deep faith kept students coming for decades.

Like most Copper Country churches, however, Sacred Heart faced challenges not of its making. Following the armistice of World War I, the price of copper plummeted in the face of excess supply. Mines began to close and lay off workers, who departed to find jobs elsewhere. The Great Depression only made the problem worse. The population of Calumet Township declined from a high of 32,000 in 1910 to only 13,000 in 1940. As the century wore on, profitable copper in the Keweenaw became harder to obtain, and other, urban industries lured young people away. By 1970, the township was home to just over 8,000 residents. The ethnic parishes that had formed when Calumet was at its zenith–the ones that still survived–consolidated into the Slovenian building, rechristened St. Paul the Apostle. Sacred Heart remained its own parish. Meanwhile, a fad of architectural modernization gripped American Catholicism, and Sacred Heart lost its magnificent altar and paintings to simpler, starker replacements. Its belfry also fell victim to structural worries, diminishing the steeple.

But much worse would come–and soon.

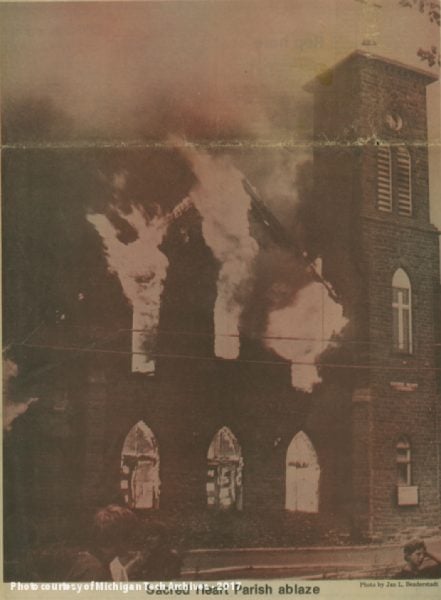

On Saturday, August 13, 1983, parishioners gathered as usual for evening Mass. The Catholic Church’s three-year calendar of Mass readings, determined for the whole church several decades before, had selected for that day a passage from the Gospel of Luke. Father Casper Gensler rose and read the Gospel, which began, “Jesus said to his disciples: ‘I have come to light a fire on the earth. How I wish the blaze were ignited!’”

At the time, no one saw extraordinary significance in this. In two hours, that changed.

Witnesses told different stories about how the fire began. A woman sitting on her porch across the highway related hearing an explosion and watching Sacred Heart’s stained glass windows shatter. “I saw the big picture window blow right out,” she told a Copper Island Sentinel reporter. “I never saw anything go up so fast.” A Sacred Heart parishioner heading to dinner with her family after Mass saw what she thought was dust in front of the church, maybe the result of a teenager spinning doughnuts in the parking lot. When the cloud grew darker and thicker, she knew with grim certainty what was happening. She insisted there was no explosion. A roaring sound, like an approaching thunderstorm, alerted Father Gensler in his rectory office. He found the sanctuary ablaze and hurried to evacuate, turning off the gas as he departed.

Firefighters arrived quickly, but their mission was hopeless. The flames devoured everything in their path: pews, carpet, altar, furnishings. Fire shot out of every window. Smoke poured from the shortened steeple. By 7:30, half an hour after the first emergency call, Sacred Heart’s roof collapsed into the blaze. With assistance from not only the Calumet and Laurium firemen but from fire houses throughout the Keweenaw, the worst finally came under control. As crews continued to put out hot spots for the next few days, Sacred Heart’s people assessed the damage. The church had been totally gutted, and only the facade and walls stood. But the cross still remained on the steeple, and a statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary near the site remained pure white, free of smoke damage. Even the boiler had survived intact. Most mercifully, no one had been injured.

Despite these survivors, it was clear immediately that the building was a total loss. Demolition began later in the month. In the meantime, Sacred Heart borrowed space in the CLK Religious Education Center for Mass and offices. The future of the parish remained uncertain. With Calumet’s population decline, would the bishop approve replacing Sacred Heart? Or would Sacred Heart be merged with St. Paul the Apostle permanently? After about a year of deliberation, discussion, and study, Bishop Mark Schmitt gave the rebuilding his blessing. Groundbreaking on a contemporary church seating 350 to 450 people took place in May 1985. A dedication Mass and reception followed a year later, with parishioners overjoyed to be back in their own building.

Now well past its 150th birthday as a parish, Sacred Heart continues to serve the Catholics of Calumet. It has seen the meteoric rise of the mines and their slow decline, the bitterness of the 1913-1914 strike, the growth and contraction of the neighborhood around it, the arrival of the Franciscan Fathers and their 2001 departure. Like so many other local institutions, Sacred Heart shows the determination of Copper Country people to rise from the ashes and lead purposeful lives, no matter what trouble challenges them.

An astounding story and the irony of it with what Jesus said about lighting a fire. Well constructed and enjoyable reading