Julia Dally was a Cornishwoman by birth, blood, and upbringing. She knew, when she married a miner, that her husband might die under tragic circumstances.

Surely she did not expect that tragedy to come at the point of a gun in his sleep, thousands of miles from their native land.

Like many immigrants to the Keweenaw, Thomas and Julia Dally found themselves thrust into circumstances they never imagined when the Copper Country’s largest strike erupted in July 1913. They had come to the area in hopes of a better life, escaping sorrow at home. They did not seek to become involved in the strike by leading parades or joining the organizations supporting or opposing it. Yet forces they could not control made them a prominent part of it and Julia an emblem of something that felt like a civil war.

Julia Jane Moore was born near Sithney, Cornwall, a small parish about four miles from the sea. Like most Cornish girls, she came from a long line of miners: her father, John Edwin Faull Moore, had followed the profession of his own father, and her mother, Julia Warren, was the daughter of a tin-miner-turned-greengrocer. John and Julia married on Christmas 1871 and welcomed the younger Julia in early 1874. Within months, John Moore was dead at just 25 years of age. His wife followed the path of necessity for many widows and entrusted her daughter to her parents, William and Julia Warren, while she sought domestic work elsewhere.

Photograph by Tony Atkin, CC BY-SA 2.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9237219

Julia Jane spent most of her childhood in the Warren home. What the household might have lacked in wealth it provided in family ties, including years with her aunts Elizabeth and Margaret Ann (Peggy). In 1885, Peggy married and moved next door with her husband; around this time, Julia Warren Moore also wed again. Curiously, both sisters married men of the same name. More curiously still, Julia Jane Moore would marry a third man with an identical moniker. Perhaps her stepfather Thomas Dally, or her uncle Thomas Dally, introduced her to one of their relatives, the third Thomas Dally. Romance blossomed between the young miner and the young lady who assisted her grocer grandfather, and the two wed on February 6, 1892.

Joy came quickly for the newlyweds, but sorrow followed hard on its heels. On August 7, 1892, Ethel Annie Jane Dally was christened in Wendron, a little parish northeast of Sithney. Almost exactly a year later, the grieving parents buried their daughter in the Wendron churchyard. Thomas William Irving Dally arrived in August 1894 and passed away on a January day in 1895. Their last child, Thomas Ernest Dally, was born in Camborne in October 1898, and perhaps Julia and Thomas, Sr., felt hopeful that they might keep one of their sons and daughters. This hope was in vain, however. On March 19, 1906, Thomas Ernest died; he was just seven years old. In the Troon cemetery, a monument arose to honor him. “Beloved child of Thomas and Julia J. Dally,” read the inscription. “Loved by all and sadly missed.”

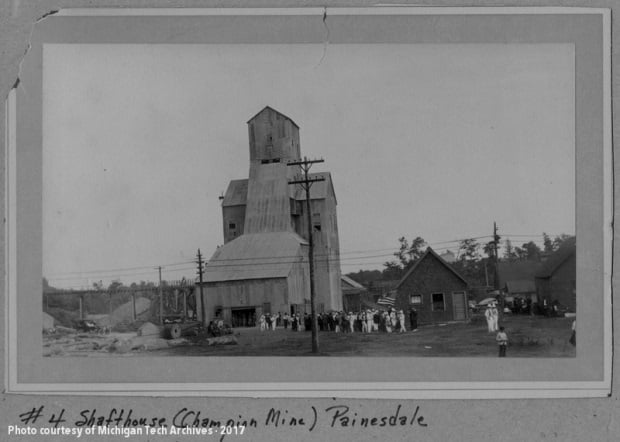

What did Cornwall have left for them? Their children were gone, at rest under mossy graves in quiet churchyards. The grandparents who had raised Julia had died in 1893 and 1905. The mines of Cornwall were no longer the envy of the world: counterparts across oceans had claimed the title as the great Cornish industry disappeared. In Michigan, a cousin, Joseph Spurr, had established himself in Painesdale as a miner with the great Copper Range Company. Encouraged by his example and apparently supported by him, Julia and Thomas sailed to America to begin a new life in a new mining district. They landed in New York City on June 8, 1910, and journeyed to Michigan. Their home now would be half of a double house, shared with Thomas’s new Copper Range colleague Adna Nicholson and his family, at the west end of Baltic Street in Painesdale.

Mining wages might have been higher and more consistent in Michigan than in Cornwall, but families often found they needed a little additional income to make ends meet. Julia and Thomas were among them. Following a path often chosen by immigrants to the Keweenaw, they opened their side of the three-story double house to boarders. Julia’s responsibilities for cooking meals for hungry laborers and laundering bedding would have increased dramatically, but no doubt the money the men paid was welcome. Since all of the Dallys’ boarders were also recent arrivals from Cornwall, perhaps the house resounded on Sundays with songs and stories from the old country. For a few years, the Dally home was likely a peaceful one.

whose No. 4 shafthouse is seen here.

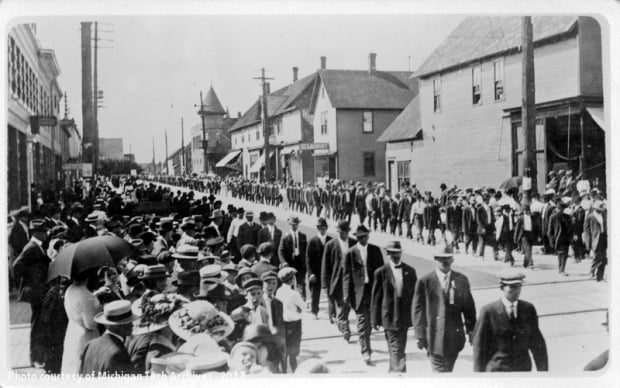

Then, on July 23, 1913, hostilities that had been simmering in the Copper Country boiled over. The five local branches of the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) began a massive strike, pushing for the resolution of grievances related to working conditions and pay. The mines, big and small alike, shut down, and Thomas Dally and all the boarders were out of work. Walking around Painesdale, one felt the tension in the air. Management deputized opponents of the strike and brought in outside guards, ostensibly in the name of keeping the peace. Strikers, their wives, and other allies participated in daily, vocal parades and allegedly set small fires around the mines.

In Seeberville, a neighborhood on the south side of Painesdale, the conflict rapidly turned bloody. On August 14, guards and company supporters arrived at the home of Joseph and Antonia Putrich, immigrants from Croatia. Like Julia and Thomas Dally, the Putrich family kept boarders of their own ethnic background, and some of these striking men had scuffled with management’s men after trespassing on mine property earlier that day. When the confrontation was renewed at the boardinghouse, it escalated to throwing projectiles. One of the company men, struck from behind, took out his gun and fired in retaliation. In the ensuing fusillade of gunfire, residents Steve Putrich and Louis (Alois) Tijan–neither of whom had been part of the original dispute–were killed. The Seeberville incident, often called the Seeberville Murders, shocked the Copper Country, and mourners and onlookers turned out by the thousands for the joint funeral. No doubt most of them felt, as they watched the cortege pass by, a solemn realization of just how rapidly the strike could get out of hand.

That same month, the mines reopened, at least on a barebones basis. Some men chose to stay on strike, believing that it was the only way to effect change. Others chose to return to work. For some of the latter, the choice might have been ideological, reflecting disagreement with the union. For others, it was no doubt one of necessity: food and clothing would not buy themselves. Seeing some neighbors taking their lunch pails to the mine while others carried picket signs did nothing to reconcile communities. Instead it introduced new opportunities for division and conflict, ones that would touch Julia and Thomas Dally deeply.

For his part, Thomas elected to return to his job at Copper Range. “Scab,” some called him derisively. We may never know whether his choice stemmed from philosophy or pocketbook, but he was far from the only Cornishman in Painesdale to make the same decision. The boarders at the Dally home joined him; further north, Calumet & Hecla reported that 98 percent of its Cornish employees had also gone back to work. In early December, hearing that tensions in the Copper Country had largely remained in check for some time, two Cornish brothers who had once lived in Painesdale returned from Canada and took up residence at the Dally boardinghouse. Thomas Henry Jane, the elder by about three years, went by Harry; the younger brother, William Arthur Jane, preferred his middle name. The Janes had immigrated to Michigan in April 1912 but left, according to their border crossing documents, about a year later. Something–perhaps the jobs vacated by strikers–enticed them to come back to Painesdale. They crossed over at Sault Ste. Marie on December 5 and arrived by train in the Copper Country shortly thereafter. Julia gave them a bed to share on the third floor of the house.

With Christmas approaching and the strike still on, Keweenaw communities needed a bit of cheer. Painesdale’s Methodists offered it in the form of a play and concert held on the evening of December 6, 1913. Julia and Thomas attended the program, along with the Nicholsons, their neighbors from the other side of their double house. Most of the Dally and Nicholson households alike tucked in for the night upon arriving home to Baltic Street, curling up under heavy quilts against the bitterly cold Copper Country air. One of Julia’s boarders, however, was expected to arrive late, well after eleven o’clock. A hospitable woman, she told Thomas she would sit up to wait for the other man’s return and offer him a cup of tea. Thomas bedded down in the parlor they had converted to a bedroom, and Julia took a book into the kitchen. For hours, she waited for the boarder’s belated arrival, alone except for her literature. Occasionally, she glanced out the front door to watch for her boarder before returning to her book. Given the normal bustle of a boardinghouse and the upheaval in her community, perhaps she welcomed the quiet solitude of the small hours.

Gunfire shattered the silence.

These WFM members were demonstrating in Laurium, adjacent to Calumet.

Bullets blasted through the double house, tearing holes in the first story all the way up to the third. Windows shattered. The Nicholson children rose from their beds; Adna, their father, ordered them to take shelter. Kenneth Nicholson, who survived the shooting at the tender age of four, remembered years later the screams and cries that echoed through the double house. “I guess I was too scared to cry,” he said. When finally the gunmen stole away into the night, the Nicholsons found bullets peppering their beds. Daughter Mary, thirteen, had been shot through the shoulder. Adna Nicholson left to fetch a doctor and to assess the situation next door. What he found was horror.

Julia had rushed into her makeshift bedroom to find her husband shot through the head. The Calumet News reported that Thomas asked his wife, “Can’t you do something for me?” before passing out. Julia was hysterical. Upstairs, the Jane brothers lay dead in the bed they shared. Gunshots had perforated Arthur’s lung and backbone; a bullet had passed through Harry’s brain. They would never start their jobs at Copper Range.

The doctor Adna Nicholson had fetched came to examine Thomas before going next door to tend to Mary. It was his sad duty to inform Julia that she would become a widow in a matter of hours. Thomas’s head injury was too severe to survive, and he never regained consciousness. At about five o’clock on December 7, just under eighteen hours after he was shot, Thomas Dally died. Julia, who had already lost so much, was now left to mourn her husband of twenty-one years.

News of the Dally-Jane murders spread rapidly through the Copper Country and, like many strike events, was picked up by newspapers far outside of Michigan. Women from the Calumet Congregational Church sent a message of consolation to Julia, offering their condolences on “the tragic death of your beloved husband, the sharer of your life’s labors, joys, and sorrows for many years.” In a front page story on December 8, the Calumet News reported on “a big, enthusiastic mass meeting held under the auspices of the Citizens’ Alliance”–a local organization opposed to strike activities–at the Calumet Armory. “A large majority of those in attendance were members of the Citizens’ Alliance and it was the first definite step taken by that organization to carry out its object ‘that violence, intimidation and disregard of law and order must be brought to an end.’” The organization had formed just weeks before the Painesdale shootings, which galvanized them to action against the WFM like nothing yet had. A.E. Petermann, a prominent local businessman, was quoted in the December 11 issue as urging Citizens’ Alliance members to “come clean in this strike,” to refrain from anything that might leave them with “blood on your hands”: “We can’t get down to the same class as these hirelings of the Western Federation of Miners.” Despite Petermann’s widely-publicized warning, within weeks the name of the Citizens’ Alliance would become forever linked with the Copper Country’s greatest loss of life.

In the meantime, there were sad necessities to be addressed. The Sons of St. George, an English fraternal organization to which all three men had belonged, supplied a burial plot for Thomas and the Janes at Houghton’s Forest Hill Cemetery. The Painesdale Methodist Episcopal Church, where Thomas Dally had spent his last evening, hosted the funeral on December 10. When the service concluded, the men’s caskets were placed on a Copper Range Railroad train and taken to the Houghton depot. Copper Range itself announced that its mills, mines, and offices would be shuttered that day to permit employees to attend the funeral and burial. Photographs captured in Houghton that day showed massive crowds in coats and hats packing the sidewalks, trying to catch a glimpse of the horse-drawn horses–one black, two white–as they passed by. By day’s end, the Jane brothers and Thomas Dally rested in peace. It would be a long time before the Copper Country knew the same peace.

Kenneth Nicholson, the four-year-old shooting survivor, recalled that Copper Range moved Julia Dally out of her home soon after the murders. The boardinghouse was no more. A tumultuous December followed, reaching a tragic pinnacle on Christmas Eve. In Calumet, the crown jewel of the Copper Country, 73 people, mostly children, died on the stairs of the Italian Hall as they fled a fire that never existed. For a century afterward, it would be said that the man who falsely shouted “Fire!” wore a membership button of the Citizens’ Alliance–the organization spurred to action by the Dally-Jane murders. Calumet marked a bitter Christmas, buried its dead, and sought answers; the death of Julia’s husband and boarders went almost forgotten through a desolate winter. Then, suddenly, on February 28, 1914, the Dally-Jane murders were back in the newspaper.

“CONFESSION MAY SOLVE PAINESDALE MURDER MYSTERY,” proclaimed the Calumet News in a banner headline. John Huhta, a former secretary of the South Range WFM local, had confessed to Houghton County Sheriff James Cruse the day before. The confession “for the greater part was voluntary,” said the newspaper in an odd turn of phrase; in the process, Huhta had implicated several other South Range union members: organizer Nick Verbanac and rank-and-file members Hjalmar Yalonen and Joseph Juntunen. A fifth man allegedly involved in planning the shooting went unnamed. According to the News, which made no secret of its stance on the union, Huhta “wearied of the methods of the methods of the Western Federation” and felt that “the federation was responsible for the circumstances that have been thrust upon him.” The shooting was apparently intended as both intimidation and retaliation, with Thomas Dally and the Janes standing in for all Cornish miners who had returned to work. Over the next few months, confessions would be given, recanted, and then reaffirmed, and ultimately only Huhta was convicted in November 1914. He had contracted tuberculosis while awaiting his trial and died of it at the Marquette Branch Prison on May 24, 1918, aged 27.

And what became of Julia Jane Moore Dally, the widow whose loss became such a public element of a vicious community battle? After providing testimony about her husband’s death that figured into Huhta’s conviction, she faded from the public eye. On December 17, 1914, she married again. Her new husband was Bert Williams, a miner fourteen years her junior also related to Joseph Spurr, the cousin who had been the Dallys’ first contact in the Copper Country. Whether out of love or loneliness, Bert and Julia formed a connection in the wake of the strike. Julia’s discovery that she was pregnant again at 40 likely prompted their marriage, and the newlyweds settled down in Painesdale to await the arrival of their child. Julia Rosemond was born a month early in mid-June 1915. Tragically, her mother had developed eclampsia, a severe hypertensive complication of pregnancy that results in repeated seizures, coma, and eventually death. Julia Jane Williams survived only one day of symptoms, dying on June 17, 1915. She was interred beside Thomas Dally in Houghton.

Julia Rosemond, who preferred her middle name in her youth, spent the first part of her youth in Norway, Michigan, with her aunt Mabel Williams Hooper. After Bert married Joseph Spurr’s widow, Theresa, Rosemond became part of a large mixed family in Detroit, where she attended high school. She married at 18, divorced her husband for cruelty a year later, and remarried to Stanley Belcher. Together, they had a daughter, Sharon, ending a line of Julias that extended back over a century.

Like most of us, Julia Jane Moore chose the path of her life, but she could not control the forces that would thrust her into the heart of Copper Country history. Her years of tumult and tragedy made her stand out among the women of her time and yet placed her firmly among them, as well. A modest headstone in Forest Hill Cemetery betrays none of the tribulations that challenged Julia, now finally at rest.

Photograph by the author.

You can read more about the Dally-Jane murders by checking out Kenneth Nicholson’s memoirs at Kevin Musser’s Copper Range website. Nicholson’s memories are supplemented (and corrected) by “Calumet News” coverage available through the Michigan Tech Archives and scholarly and popular publications like Larry Lankton’s “Cradle to Grave” and Gary Kaunonen and Aaron Goings’s “Community in Conflict.”

What an interesting story but so so heartbreaking! The folks suffered so much and it is nice that someone remembers . Thank You Emily Schwiebert for remembering