More than 90 percent of US medical expenditures are spent on caring for patients who cope with chronic diseases. Some patients with congestive heart failure, for example, wear heart monitors 24/7 amid their daily activities.

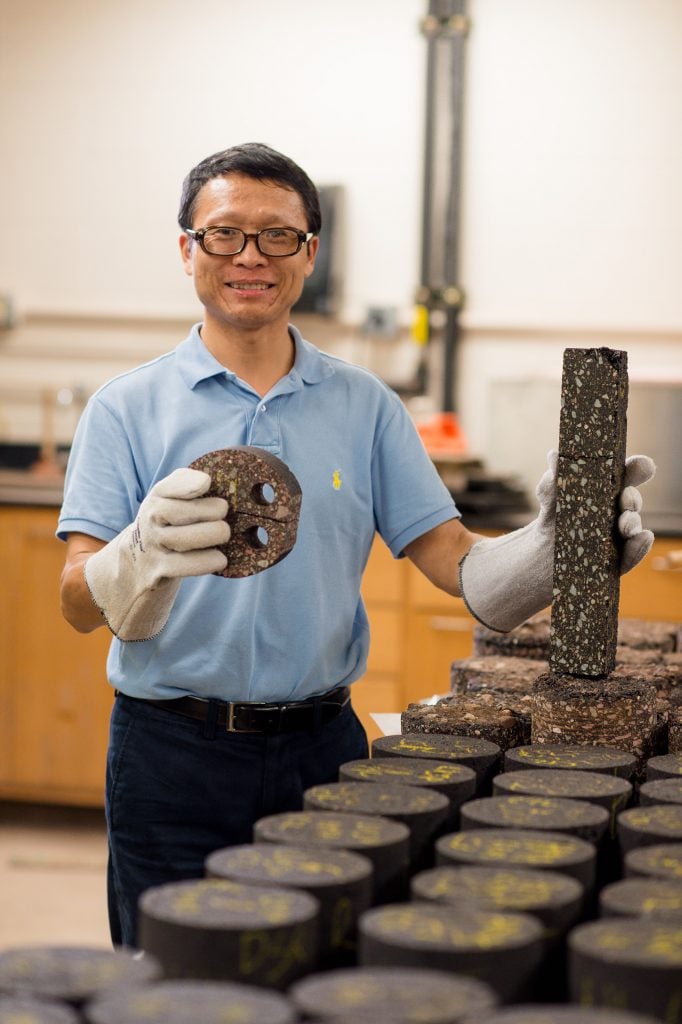

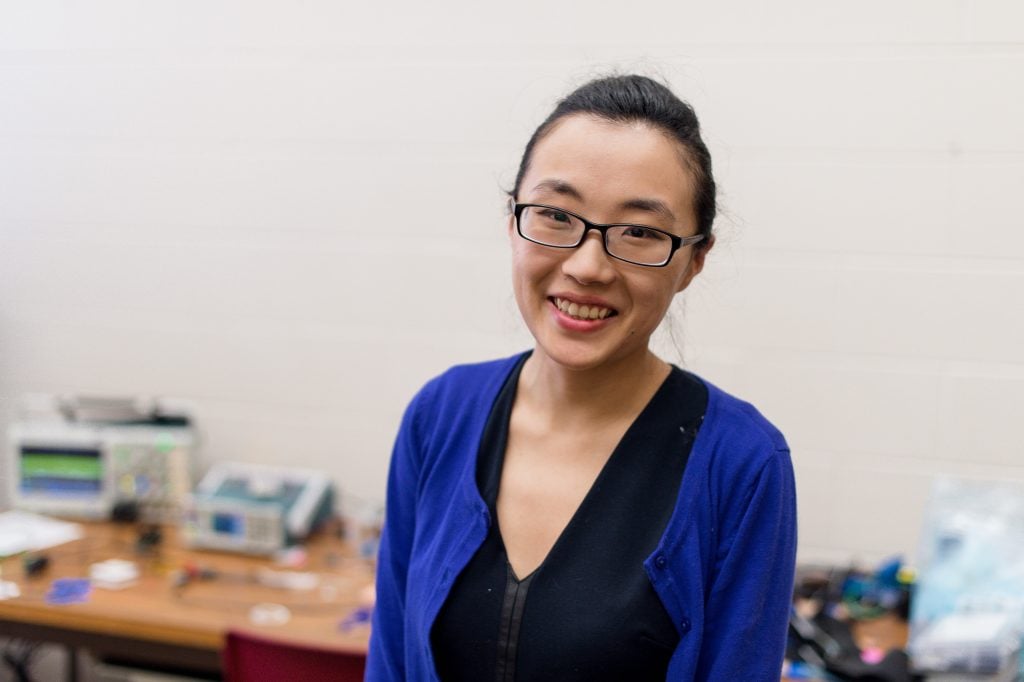

Michigan Tech researcher Ye Sarah Sun develops new human interfaces for heart monitoring. “There’s been a real trade-off between comfort and signal accuracy, which can interfere with patient care and outcomes,” she says. Sun’s goal is to provide a reliable, personalized heart monitoring system that won’t disturb a patient’s life. “Patients need seamless monitoring while at home, and also while driving or at work,” she says.

Sun has designed a wearable, self-powered electrocardiogram (ECG) heart monitor. “ECG, a physiological signal, is the gold standard for diagnosis and treatment of heart disease, but it is a weak signal,” Sun explains. “When monitoring a weak signal, motion artifacts arise. Mitigating those artifacts is the greatest challenge.”

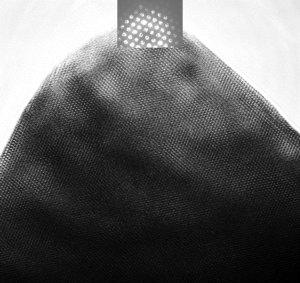

Sun and her research team have discovered and tapped into the mechanism underlying the phenomenon of motion artifacts. “We not only reduce the in uence of motion artifacts but also use it as a power resource,” she says.

Their new energy harvesting mechanism provides relatively high power density compared with traditional thermal and piezoelectric mechanisms. Sun and her team have greatly reduced the size and weight of an ECG monitoring device compared to a traditional battery-based solution. “The entire system is very small,” she says, about the size of a pack of gum.

“We not only reduce the influence of motion artifacts but also use it as a power resource.”

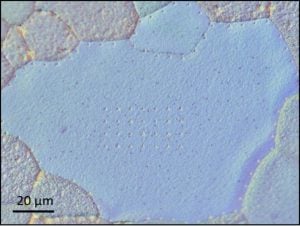

Unlike conventional clinical heart monitoring systems, Sun’s monitoring platform is able to acquire electrophysiological signals despite a gap of hair, cloth, or air between the skin and the electrodes. With no direct contact to the skin, users can avoid potential skin irritation and allergic contact dermatitis, too—something that could make long-term monitoring a lot more comfortable.