In the aftermath of the eruption of Volcán de Fuego in Guatemala, the risk now is for lahars triggered by extreme rain events. Guatemala’s rainy season started in May and typically runs through the month of October. Lahar hazards are the result of fresh (loose) eruptive deposits on steep slopes that experience heavy rainfall, creating mud and debris flows that can scour landscapes and inundate lower lying areas. The hazards are exacerbated by the steepness of the slopes, recent loss of vegetation, and the rainy season.

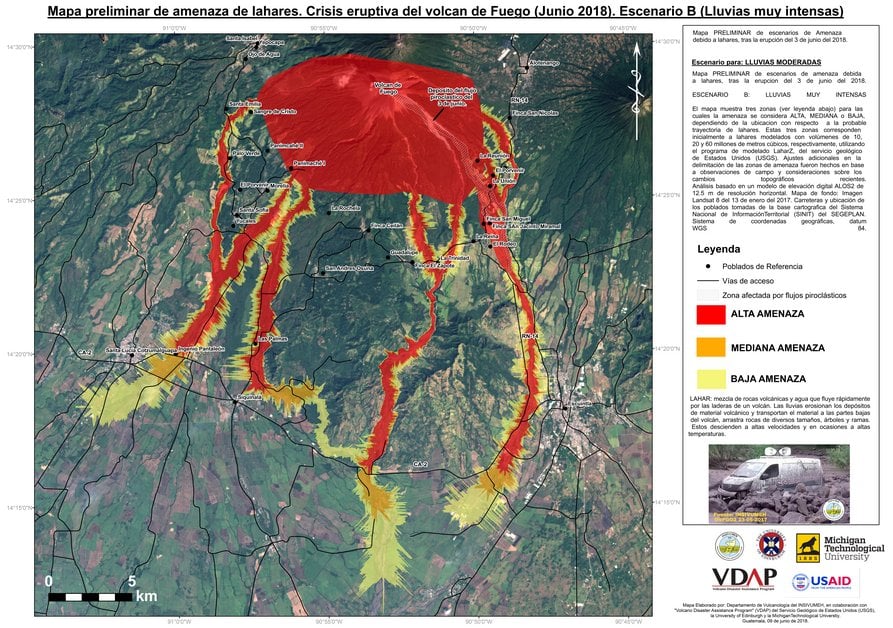

Rudiger Escobar Wolf, a volcanologist at Michigan Technological University and native of Guatemala, shares a set of preliminary crisis hazard maps of the threat of lahars at Fuego volcano in Guatemala, created with INSIVUMEH, Guatemala’s Instituto Nacional de Sismologia, Vulcanologia, Meterologia e Hidrologia, as well as USGS/VDAP, and others.

Lahars often initiate at upper most elevations and flow down through stream channels and gullies. Scientists forecast lahar hazards using computer models of the slopes in conjunction with estimates of the lahar volume at the outset, which is very challenging to estimate. For instance, in October 2005, Santa Ana erupted in El Salvador and lahars from this fresh ash were triggered overnight due to Hurricane Stan. And in November 2009, Hurricane Ida triggered devastating lahars from San Vicente volcano. Those deposits were from a large eruption of a nearby Ilopango Volcano that occurred more than 1500 years prior and had been sitting precariously on the slopes of San Vicente until 36″ of rain fell in 18 hours.

Escobar Wolf has worked on the most active three volcanoes in Guatemala (Fuego, Pacaya, and Santaguito) since he was a little boy. Michigan Tech Volcanology Professor (Emeritus) Bill Rose and others worked with him as a young adult and recruited him to Michigan Tech for graduate studies. Escobar Wolf is in frequent communication with CONRED (sort of like FEMA) and INSIVUMEH (sort of like USGS) about the eruptive symptoms of Guatemala’s active volcanoes.

The eruptive activity of Fuego Volcano is so frequent, in fact, it is the classic “cry wolf” scenario.

“Most volcanoes are either ‘on’ or ‘off’, but Fuego has been simmering since 1999,” says Kyle Brill, a doctoral candidate in geophysics at Michigan Tech. Brill also monitors seismic activity at Fuego Volcano. “Less than one percent of the volcanoes around the world have had eruptions lasting longer than a decade, and Guatemala has three volcanoes that always seem active to some level,” he says. “Questions naturally arose in hindsight in the days following the eruption as to why people around Fuego didn’t receive/heed evacuation warnings earlier, and the answer to that, sadly, was that Fuego is so active normally that it is very difficult to forecast when changes in activity could become deadly.”

Brill is a returned Peace Corps volunteer. He served in Guatemala under the Environmental Conservation and Income Generation Program as a Master’s International student in the Mitigation of Natural Geologic Hazards program at Michigan Tech.

Despite the frequent eruptive behaviors, aspects of this eruption were much different than recent events at Fuego. In particular, some of the pyroclastic flows overbanked the drainages.

NPR’s Here & Now on WBUR-FM features an interview with Rudiger Escobar Wolf, Ph.D. ’13, MS ’07, talking about the Volcán de Fuego eruption. Listen at “Rescue Operations Underway In Guatemala After Deadly Volcano Eruption”

Find out more about lahars from the USGS Volcano Hazards Program

Check out drone footage taken one week after the eruption of Volcán de Fuego, by Jozef Stano