Dr. Becky Ong generously shared her knowledge on Husky Bites, a free, interactive Zoom webinar hosted by Dean Janet Callahan. Here’s the link to watch a recording of her session on YouTube. Get the full scoop, including a listing of all the (60+) sessions at mtu.edu/huskybites.

Fungus Breath? It’s a good thing!

Enter the magical world of herbology and potions with Dr. Becky Ong. Learn how to make your own color-changing potion and use it to find the best conditions to generate and collect fungus breath. Discover the science behind the magic, what makes plants and microbes so cool.

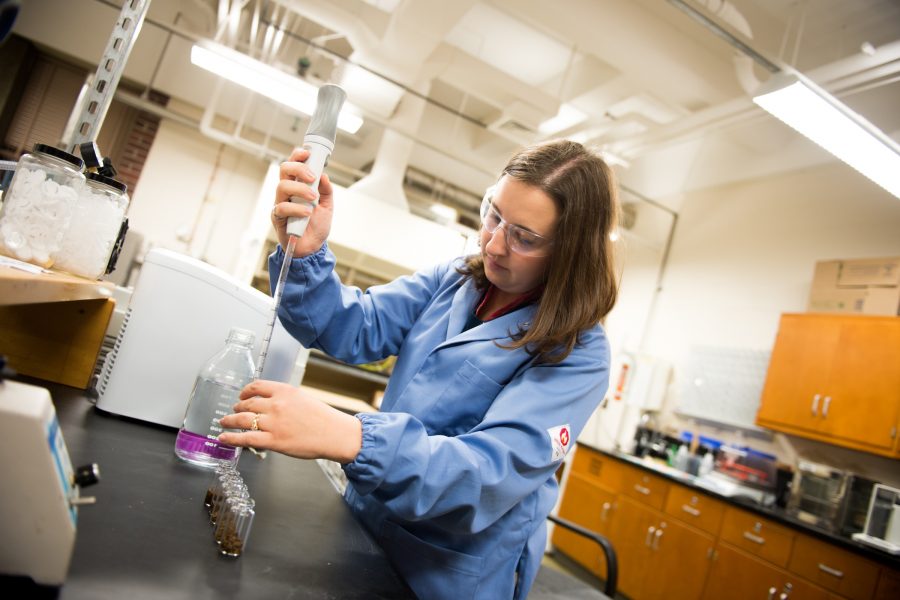

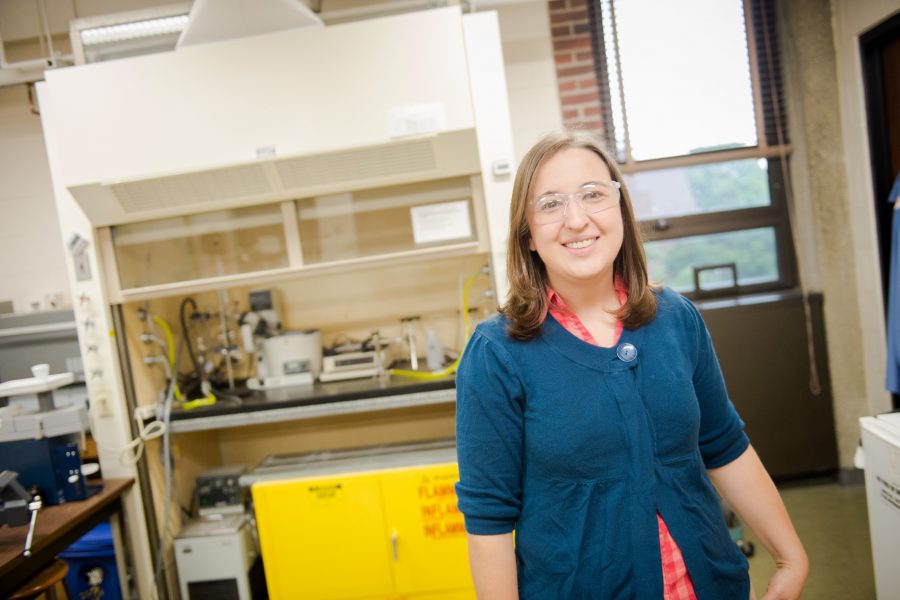

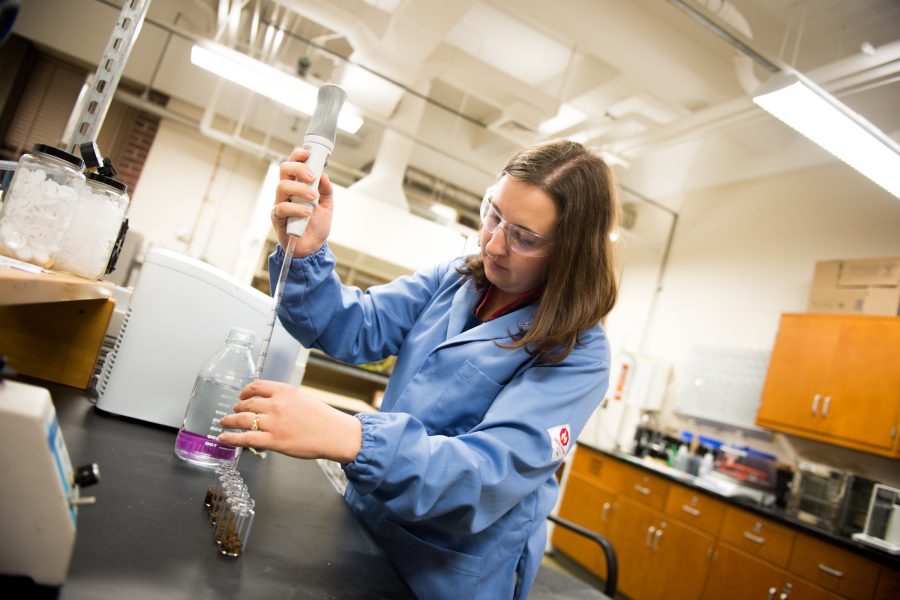

Dr. Ong, an assistant professor of chemical engineering, runs the Biofuels & Bio-based Products Lab at Michigan Tech, where she and her team of student researchers put plants to good use.

“As engineers we aren’t just learning about the world, but we’re applying our knowledge of the world to make it a better place,” she says. “That is what I love. As a chemical engineer, I get to merge chemistry, biology, physics, and math to help solve such crazy huge problems as: how we’re going to have enough energy and food for everyone in the future; how we’re going to deal with all this waste that we’re creating; how to keep our environment clean, beautiful and safe for ourselves and the creatures who share our world.”

Dr. Ong, a born Yooper, is a Michigan Tech alumna. She graduated in 2005 with two degrees, one in Biological Sciences, and the other in Chemical Engineering. She went on to Michigan State University to earn a PhD in Chemical Engineering in 2011. Growing up, she was one of the youngest garden club enthusiasts in northern Michigan, a science-loving kid who accompanied her grandparents to club events like “growing great gardens” or “tulip time.” When she wasn’t tending the family garden, she was “mucking about in nature” learning from parents who had both trained as foresters.

Q: When did you first get into engineering? What sparked your interest?

I first became interested in engineering in high school when I learned it was a way to combine math and science to solve problems. I loved math and science and thought that sounded brilliant. However, I didn’t understand at the time what that really meant. I thought “problems” meant the types of problems you solve in math class. Since then I’ve learned these problems are major issues that are faced by all of humanity, such as: How do we enable widespread access to clean energy? How do we produce sufficient amounts of safe vaccines and medicine, particularly in a crisis? How do we process food products, while maintaining safety and nutritional quality? As a chemical engineer I am able to combine my love of biology, chemistry, physics, and math to create novel solutions to society’s problems. One thing I love about MTU is that the university gives students tons of hands-on opportunities to solve real problems, not just problems out of a textbook (though we still do a fair number of those!). These are the types of problems our students will be solving when they go on to their future careers.

Q: Tell us about yourself. What do you like to do outside the lab?

I’m a born Yooper who grew up in the small-town northern Lower Peninsula of Michigan and came back to the UP for school.

I love the Copper Country and MTU students so much, I managed to persuade my husband to come back to Houghton 5 years ago. Now I live near campus with my husband, 4-year-old daughter, our Torbie cat and our curly-haired dog.

We read science fiction and fantasy stories; play board games; kayak on the canals and lakes while watching for signs of wildlife; make new things out of yarn, fabric, wood, and plastic (not all at the same time)—and practice herbology (plants and plant lore) and potions in the garden and kitchen.

Huskies in the Biofuels & Bio-based Products Lab at Michigan Tech

Biofuels and Dry Spells: Switchgrass Changes During a Drought

Sustainable Foam: Coming Soon to a Cushion Near You

Want to know more about Husky Bites?