Raymond Shaw and Will Cantrell generously shared their knowledge on Husky Bites, a free, interactive Zoom webinar hosted by Dean Janet Callahan. Here’s the link to watch a recording of his session on YouTube. Get the full scoop, including a listing of all the (60+) sessions at mtu.edu/huskybites.

What are you doing for supper this Monday night 12/7 at 6 ET? Grab a bite with Dean Janet Callahan and Raymond Shaw, Distinguished Professor of Physics and Director of the Atmospheric Sciences program at Michigan Tech.

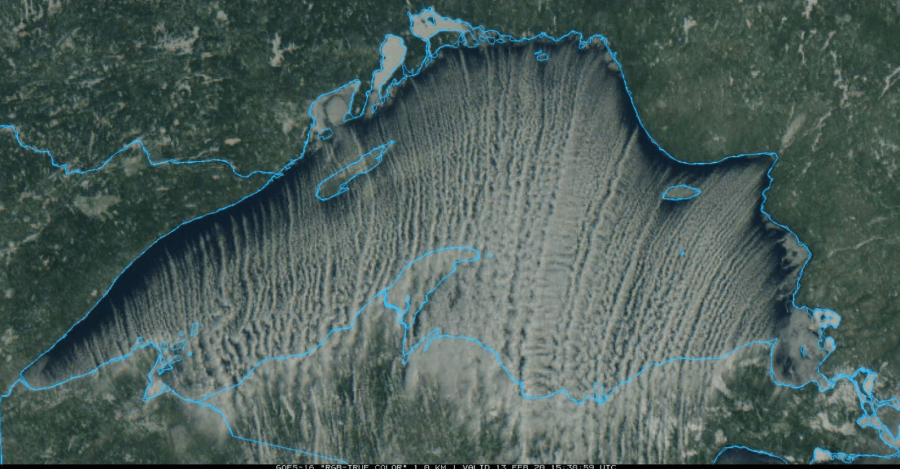

During Husky Bites, Prof. Shaw will describe the simple—and some of the not-so-simple—science of lake effect snow, and what makes the Keweenaw an ideal spot for epic snowfalls.

Also joining in, Will Cantrell, associate provost and dean of Michigan Tech’s graduate school. Dean Cantrell is also a professor of physics. His research focuses on atmospheric science, particularly on clouds.

So how can it be clear and sunny in one place, while 5 miles away it’s snowing cats and dogs? Shaw is ready to explain during Husky Bites. He is a world expert on cloud physics, atmospheric turbulence, and ice nucleation.

“Snow itself doesn’t just materialize out of thin air,” Shaw says. “For a snowflake to form, first a particle of dust, a nucleus, is needed. Water molecules attach themselves to this particle and then freeze as they’re carried high in the atmosphere by winds.”

“Yet, within a few hours, you basically purge the atmosphere of all those particles,” adds Shaw, “So how can it snow for days on end?”

Clouds are an integral part of the Earth’s environment—providing the water we drink, cleaning the air we breathe, and influencing the climate in which we live. “We want to understand the clouds,” he says.

To study clouds, Shaw and his team of researchers sometimes go inside, using holography and an airplane lab, or by dropping a pendulum-type device from a helicopter. He’s also studied clouds on a mountain top, where the most valuable tool is patience. “It can be very frustrating seeing a cloud hover fifty feet above you, but when it descends and you’re inside the cloud it is definitely worth the wait.”

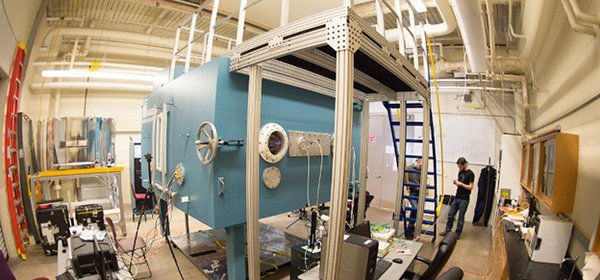

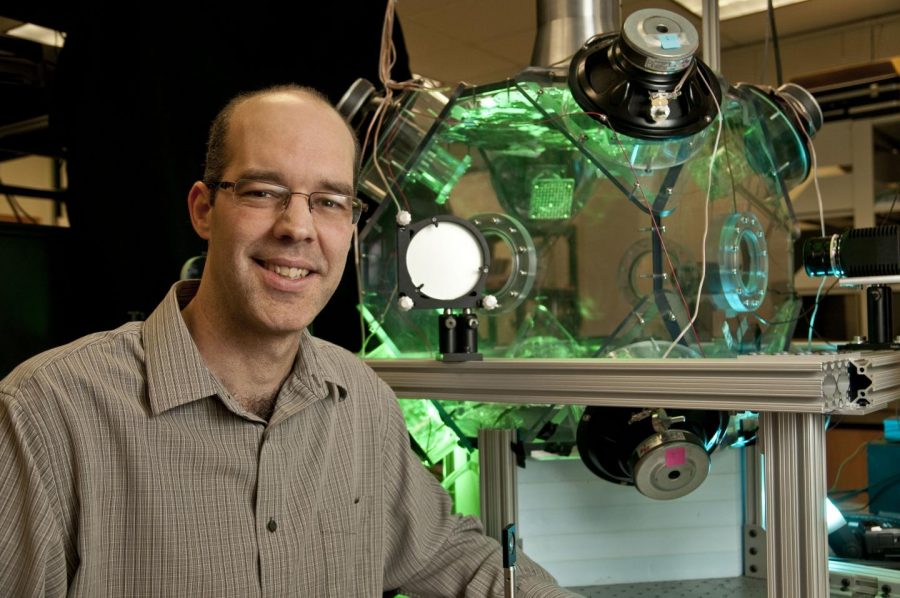

Luckily, Shaw, Cantrell, and other atmospheric science researchers at Michigan Tech don’t cross their fingers and hope for cooperative weather—the University’s innovative Pi Cloud Chamber allows them to head into the lab and make their own.

“This unique chamber is used for investigating aerosol and cloud processes relevant to weather and climate. To make a cloud, the environment has to have a relative humidity above 100 percent,” Shaw explains.

“In the lab that’s a tricky thing to achieve because water condenses on any available surface. The MTU Pi cloud chamber gets around that by generating clouds through turbulent mixing,” he says.

“The Pi cloud chamber allows us to study a wide variety of research questions,” adds Shaw, “For example, how do clouds respond to clean versus polluted conditions?”

And for us, here in Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula, home of Michigan Tech, it helps answer one of our most vexing questions: “How does Lake Superior end up in my driveway?

After earning his PhD at Penn State, Shaw was a postdoc research fellow at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colorado. He joined the faculty at Michigan Tech and soon earned a National Science Foundation CAREER award and then a NASA New Investigator Program award. As part of his research he collaborates with NCAR and international scientists at the Institute for Tropospheric Research in Leipzig, Germany, Peking University in Beijing, China, and the Max Planck Institute for Dynamics and Self Organization in Göttingen, Germany.

While Shaw finds research personally rewarding, there is ultimately a higher purpose. “Of course, the ultimate hope is that what my students, colleagues and I learn will somehow contribute to humanity, to our collective understanding and to our well being.”

Prof. Shaw, when did you first get into physics? What sparked your interest?

Physics captured my attention because it was possible to solve so many different types of problems with just a few simple truths. Physics is a good subject for someone with a poor memory!

How did you make the leap to atmospheric physics?

I remember earning my weather badge as a cub scout, and really disliking all the memorization of cloud types, like stratocumulus and cirrus. But I was fortunate to grow up around people who were interested in ideas rather than nomenclature, and eventually I became fascinated with what makes ice crystals grow in different shapes. I loved physics as an undergrad, and the ice crystal question was enough of a nudge to search for a graduate program in which I could combine physics with the atmosphere.

Hometown, Hobbies, Family?

I was raised in Fairbanks, Alaska. I’ve been living “down south” in the Keweenaw for over 20 years. My family and I love the snow… most of the time. Cross country skiing and snow biking are two of our favorite winter activities.

Research is inspiring, nature is so profoundly beautiful and subtle, it’s a privilege to spend so much of my time trying to understand bits and pieces of it.

Dean Cantrell is a member and former director of the Earth, Planetary and Space Sciences Institute, which promotes research and education in interdisciplinary areas spanning Earth, its ecosystems, and intergalactic space.

As Dean of the Graduate School, Cantrell emphasizes that graduate education at Michigan Tech is a unique combination of the questions “Why?” and “How?” with theory and practice.

“That’s a powerful combination, and our students are valued by industry and by other academic institutions because of it,” he said.

Dean Cantrell, how did you first get into Physics, and then Atmospheric Science?

When I started my undergraduate studies, I intended to get degrees in Physics and engineering. (I hadn’t decided just what kind of engineer yet.) But I started taking Physics classes first and decided to just do that. When I graduated, I didn’t want to do any of the “traditional” routes like solid state or atomic and molecular, so I branched off into Atmospheric Science.

“I always tell my students, ‘don’t do what I did.’ I was young, single, with no dependents, so I thought, why not go to Alaska? Though, actually, it turned out to be a very good decision—and it really prepped me for Michigan Tech, too (we get a lot of snow here in Houghton each year).

I never had to shovel my roof in Fairbanks, but there were times when it would warm up to -20 degrees F and it actually felt warm. In Fairbanks, if it’s been -40 for a few weeks, and then it goes up to -20—when you go outside, you undo the top button on your coat!”

Hometown and Hobbies?

I grew up on a small farm just outside of Hendersonville Tennessee. I’ve lived in St. Louis Missouri; Fairbanks Alaska; Seattle, Washington; Bloomington Indiana; and Houghton, Michigan. In the summer, I fly fish and occasionally tie some of my own flies.

Read more:

Six Questions with Distinguished Professors Raymond Shaw

Rainmakers: The Turbulent Formation of Cloud Droplets

Why it Snows so Much in the Frozen North

Teamwork: New Graduate school Dean Begins Duties

Watch more:

“The Pi Chamber is so named because it has an inner, working volume of 3.14 m3 (when we select a cylindrical wall boundary, with a diameter of 2 m and a height of 1 m). It also happened to be delivered to MTU on March 14, pi day, but that was a coincidence.”