Greg Odegard shares his knowledge on Husky Bites, a free, interactive webinar this Monday, November 8 at 6 pm ET. Learn something new in just 20 minutes (or so), with time after for Q&A! Get the full scoop and register at mtu.edu/huskybites.

What are you doing for supper this Monday night 11/8 at 6 pm ET? Grab a bite with Dean Janet Callahan and Greg Odegard, Professor of Mechanical Engineering-Engineering Mechanics at Michigan Tech.

It’s a bit of a conundrum. When sending humans into space for long periods of time, a significant amount of mass (food, water, supplies) needs to be put on the rockets that leave Earth. More mass in the rocket requires more fuel, which adds more mass and requires more fuel. Current state-of-the-art structural aerospace materials only add more mass, which requires—you guessed it—more fuel.

During Husky Bites, Professor Greg Odegard will share how his team of researchers at Michigan Tech go about developing new ultra-light weight structural materials to significantly cut fuel costs for sending humans to Mars—and beyond.

Joining in will be ME-EM department chair Bill Predebon. Dr. Predebon has been at Michigan Tech since 1975. That’s 46 years, and 24 years as department chair. He plans to retire this summer.

“Bill Predebon has been my mentor since I came to Michigan Tech in 2004. I have enjoyed working for him, and I am not ready for him to retire,” says Odegard. “I was extremely impressed with him during my job interview in 2003, which is one of the biggest reasons I came to Michigan Tech.”

In addition to teaching classes and mentoring students at Michigan Tech, Odegard leads the charge in developing a new lighter, stronger, tougher polymer composite for human deep space exploration, through the Ultra-Strong Composites by Computational Design (US-COMP) Institute.

The NASA-funded research project brings together 13 academia and industry partners with a range of expertise in molecular modeling,manufacturing, material synthesis, and testing, now in the final year of the five-year project.

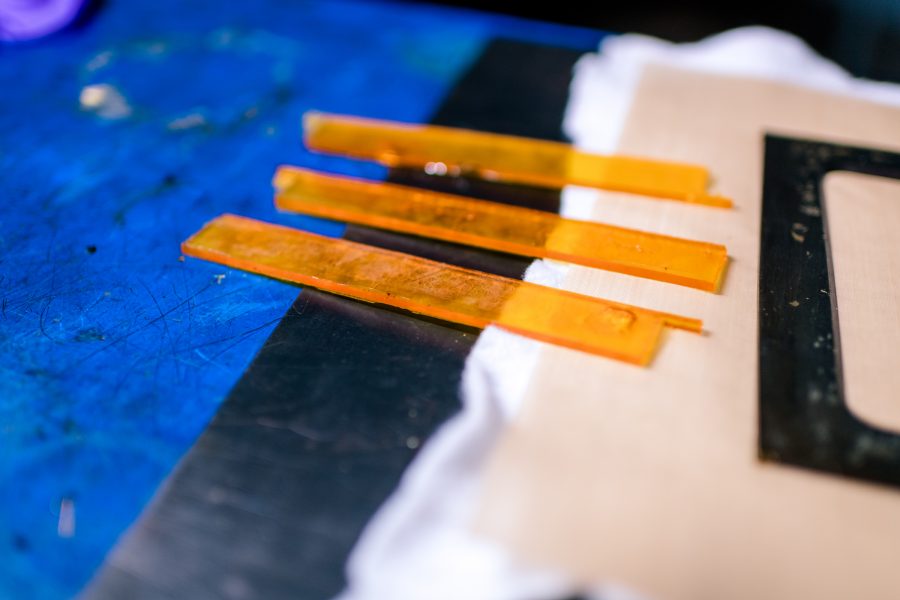

US-COMP’s goal is to develop and deploy a carbon nanotube-based, ultra-high strength lightweight aerospace structural material within five years. And US-COMP research promises to have societal impacts on Earth as well as in space, notes Odegard. Advanced materials created by the institute could support an array of applications and benefit the nation’s manufacturing sector.

The material of choice, says Odegard: carbon. He specifically studies ultrastrong carbon-nanotube-based composites. But not all carbon is equal, notes Odegard. Soft sheets of graphite differ from the rigid strength of diamond, and the flexibility and electrical properties of graphene.

“In its many forms, carbon can perform in many ways. The tricky part with composites is figuring out how different materials interact,” he explains.

Odegard and his research team use computational simulation—modeling—to predict what materials to combine, how much and whether they’ll stand up to the depths of space. “When we began developing these ultra-strong composites, we weren’t sure of the best starting fibers and polymers, but over time we started to realize certain nanotubes and resins consistently outperformed others,” says Odegard. “Through this period of development, we realized what our critical path to maximize performance would be, and decided to focus only on that, rather than explore the full range of possibilities.”

“I have the most fun working with my students and the broader US-COMP team. Our whole team is excited about the research and our progress, and this makes for some of the best research meetings I have experienced in my career.”

The challenge when working with carbon nanotubes is their structure, says Odegard. “Under the most powerful optical microscope you see a certain structure, but when you look under an SEM microscope you see a completely different structure,” he explains. “In order to understand how to build the best composite panel, we have to understand everything at each length scale.”

The US COMP Institute has created dedicated experiments and computational models for the chosen carbon nanotube structure, something that must be done for each length scale, from the macro to the atomic.

As their project comes to a close, they’ve zeroed in how just how polymer can be used with carbon-nanotubes to form ultra-strong composites.

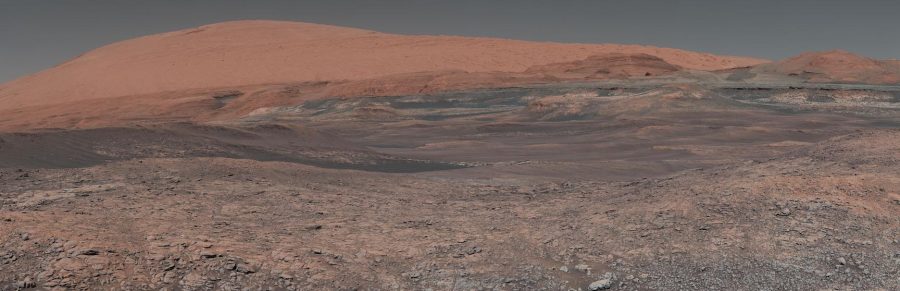

NASA’s Mars Curiosity rover took this mosaic image, looking uphill at Mount Sharp.

US-COMP PARTNERS

- Florida A&M University

- Florida State University

- Georgia Institute of Technology

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Pennsylvania State University

- University of Colorado

- University of Minnesota

- University of Utah

- Virginia Commonwealth University

- Nanocomp Technologies

- Solvay

- US Air Force Research Lab

“As a group we have been able to push the envelope way beyond where we started in 2017—expanding the performance in a very short time period,” says Odegard. “This was made possible through remarkable collaboration across the institute.”

Before Predebon convinced him to join the faculty at Michigan Tech, Odegard worked as a researcher at NASA Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. Odegard’s research has been funded by NASA, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, Mayo Clinic, Southwestern Energy, General Motors, REL, and Titan Tires. As a PI and co-PI, he has been involved in externally funded research projects totaling over $21 million. Odegard was a Fulbright Research Scholar at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. In 2019 he was elected a Fellow of ASME, in recognition of his significant impact and outstanding contributions in the field of composite materials research.

Prof. Odegard, how did you first get into engineering? What sparked your interest?

Growing up, I always knew that I would be an engineer. I was always interested in airplanes and spacecraft.

Hometown, family?

I grew up and went to college in the Denver area. I was already accustomed to snow when I moved to Michigan.

Any hobbies? What do you do in your spare time?

In the summer, I enjoy running, mountain biking, hiking, basketball, and soccer. In the winter, I like cross-country skiing and downhill skiing. I also enjoy cooking, traveling, and anything fun with my family.

Dr. Predebon, how did you first get into engineering? What sparked your interest?

During my childhood my dad introduced me to model trains. We had a large 8ft x 4ft board with Lionel trains. I learned how they work and how to set it up. That sparked my interest in engineering.

Hometown, family?

I was born in Trenton, New Jersey. I had one brother, Peter, who is deceased now.

What do you like to do in your spare time?

For most of my career at Michigan Tech my hobby has been my work. My work has absorbed my life, by choice. I have a real passion for our program. However, I do enjoy exercising, repairing things, and organic gardening. My wife, Maryanne, is very good; I just help. We have a peach tree, we have grown watermelon, we’ve grown cantaloupes, we’ve grown potatoes, her passion is pumpkins so we grow these large pumpkins—150 pounds.

“The way I look at my role is to nurture the growth of my faculty and staff, right along with our students. I want to help them all reach their potential.”

Read More:

Q&A with MTU Research Award Winner Gregory Odegard

NASA Taps Tech Professor to Lead $15 Million Space Technology Research Institute