John Vucetich shares his knowledge on Husky Bites this Monday, November 7 at 6 pm ET. Learn something new in just 30 minutes (or so), with time after for Q&A! Get the full scoop and register at mtu.edu/huskybites.

Restoring the Balance: What are you doing for supper this Monday 11/7 at 6 pm ET? Grab a bite on Zoom with Dean Janet Callahan and John Vucetich, Distinguished Professor, College of Forest Resources and Environmental Science at Michigan Tech.

Prof. Vucetich studies the wolves—and the moose that sustain them—of the boreal forest of Isle Royale National Park. It’s something he’s done for more than a quarter century. He joined Michigan Tech’s Isle Royale Wolf-Moose study in the early 1990s as an undergraduate student majoring in biological science. He went on to earn a PhD in Forest Sciences at Tech in 1999.

Three years later Vucetich began leading the study along with SFRES research professor Rolf Peterson, who is now retired. This year will be the study’s 66th year monitoring wolves and moose on Isle Royale—the longest running predator-prey study in the world. (Their project website is isleroyalewolf.org.)

“Much of my work is aimed at developing insights that emerge from the synthesis of science and ethics,” says Vucetich. “Environmental ethicists and environmental scientists have a common goal, which is to better understand how we ought to relate to nature,” he adds. “Nevertheless, these two groups employ wildly different methods and premises.”

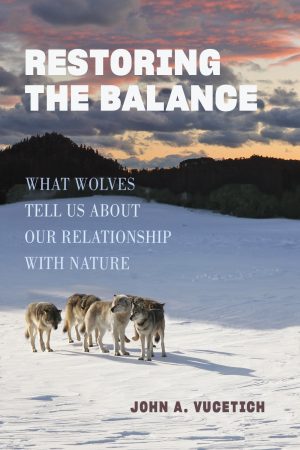

During Husky Bites, Vucetich will read from his book, Restoring the Balance: What Wolves Teach Us About Our Relationship with Nature, published by Johns Hopkins University Press in 2021.

“It’s a book about wolves,” he says, simply, “and how humans relate to wolves.”

It’s also an exhilarating, multifaceted, thought-provoking read. Vucetich combines environmental philosophy with field notes chronicling his day-to-day experience as a scientist. Examining the fate of wolves in the wild, he not only shares lessons learned from these wolves, but also explains their impact on humanity’s fundamental responsibilities to the natural world.

“Science can never tell us what we ought to do or how we ought to behave,” says Vucetich. “Science only describes the way the world is. Ethics by itself can’t tell us what to do, either. Ethics needs science—facts about the world—to be properly informed.”

“John is a real field man, a dauntingly quantitative biologist, and a dedicated student of logic: the coalescence of this whole emerges as a leading conservation ethicist,” writes David W. Macdonald, professor of wildlife conservation at Oxford University, in the foreword of Restoring the Balance. “In this book, John Vucetich asks you to imagine yourself as a young wolf, dreaming of attempting to kill your first moose, ten times your size, using only your teeth,” adds Macdonald. “He asks the big question (bravely, for a hard-nosed quantitative biologist in a profession neurotic about anthropomorphism) what is it like to be a wolf? He thinks, as do I, that this is a more sensible question than you might suspect, in part because it turns out there’s so much similarity between us and them.”

“The island is Isle Royale, a wilderness surrounded by the largest freshwater lake in the world. I make these observations from the Flagship, an airplane just large enough for a pilot and one observer. After the flight, questions hack their way through the recursive web of dendrites that is my consciousness. What is the life of a wolf like? What is it like to be a wolf? Those questions are too presumptuous. The first questions should penetrate down to the foundation: Of all the millions of species on planet Earth, why wolves, why not some other?”

Joining in during Husky Bites will be Becky Cassel. She teaches Earth science and environmental science to ninth graders at a high school outside of Hershey, Pennsylvania (Lower Dauphin School District).

“I have not met Dr. Vucetich in person. As a teacher, I have spent many years using the Isle Royale Wolf-Moose study to talk about populations and predator/prey relationships in my classroom,” says Cassel.

“For Christmas last year I gave my father a copy of Restoring the Balance. When he was done reading it, both my husband and I read it. It was riveting. I emailed Dean Callahan to suggest inviting Dr. Vucetich onto Husky Bites. The Michigan Tech Wolf-Moose study is found in every biology textbook used today. I knew many Husky Bites watchers would be familiar and interested in the topic.”

Excerpt

During Husky Bites, Prof. Vucetich will read passages from Restoring the Balance. The passage below is taken from the book’s first chapter, “Why Wolves?”

February 18. We saw what they smelled—a cow moose and her calf, who had themselves been foraging. It didn’t look good for the cow and calf right from the beginning. The calf was too far away from her mother, and they may have had different ideas about how to handle the situation. The wolves rushed in. The cow turned to face the wolves, expertly positioned between the wolves and her calf, but only for a second. The calf bolted. After a flash of confusion’s hesitation, the cow pivoted and did the same. Had she not, the wolves would have rushed past the cow and bloodied the snow with her calf. The break in coordination between cow and calf put four or five wind-thrown trees lying in a crisscrossed mess between the cow and her tender love. The cow hurled herself over the partially fallen trunks that were nearly chest-high on a moose. She caught up with her frantic calf before the wolves did. Then the chase was on, led by the least experienced of them all—the calf. The cow, capable of running faster, stayed immediately behind the calf, no matter what direction the terror-ridden mind of that calf decided to take. Every third or fourth step the cow snapped one of its rear hooves back toward the teeth of death. One solid knock to the head would rattle loose the life from, even, a hound of hell. After a couple of minutes and perhaps a third of a mile, the pace slowed. By the third minute everyone was walking. The calf, the cow, and the wolves. The stakes were high for all, but not greater than the exhaustion they shared. Eventually they all stopped. Not a hair’s width separated the cow and calf, and the wolves were just 20 feet away. The cow faced the wolves. A few minutes later the wolves walked away. By nightfall Chippewa Harbor Pack had pushed on another six miles or so, passing who-knows-how-many-more moose. Their stomachs remained empty.

Praise for Restoring the Balance:

“John Vucetich creates a masterful blend of memoir, science, and ethics with a message that is both timely and timeless.” — Michael Paul Nelson, Professor of Environmental Ethics and Philosophy, Oregon State University

“This exhilarating book is a remarkable triumph―beautifully crafted.” — David W. Macdonald, Professor of Wildlife Conservation, University of Oxford

“This book is juicy with field notes―the stories of charismatic individual wolves like the Old Gray Guy, and complex science made understandable and seductively enticing to the reader with even the tiniest interest in wolf survival and natural history.” — Nancy Jo Tubbs, Chair, Board of Directors, International Wolf Center

Becky, how did you first get into teaching? What sparked your interest?

I taught sailing lessons as a summer job in Escanaba, Michigan, while pursuing a degree at Miami of Ohio. After graduating and working for a year I realized that I really enjoyed teaching much more than my chosen career. I decided to go back and earn my Earth science teaching certification.

As a self-professed “outdoor girl”, I love all things Earth science. I was amazed how much I enjoyed every single Earth science class I needed to take in order to earn my science teacher certificate. I had been working in Pennsylvania at the time, so I earned my teacher certificate in Pennsylvania, and then was hired to teach there, too. I met my husband, Craig, and we decided to stay in Pennsylvania. Of course we travel to Escanaba every summer to get my UP fix!

Hometown, family?

My hometown is Escanaba, Michigan; however my parents are from the Philadelphia area. My father chose Michigan Tech for college (Tech Alum ’59) and fell in love with the area. The Cliff Notes version is that he returned to the East, married my mother, and convinced her to move to the UP. I was 2 months old at the time. I have an older sister (also a teacher) who lives in central Maine.

My husband Craig is a biology and anatomy teacher, and we met while teaching in the same school. We’ve driven into school together every day since then. He just retired at the end of last year, so now I drive in on my own.

We have two children. Our son, Elliot, just graduated from Virginia Tech last year and returned to college this year to earn his Earth science teacher certificate. Our daughter, Avery, chose to go to Michigan Tech like her grandfather, and entered the environmental engineering program. She has found her “outdoor people” at Michigan Tech.

Any hobbies? Pets? What do you like to do in your spare time?

I guess my biggest hobby is bicycle touring, but we also hike, run, and spend time outdoors. I grew up sailing in Esky, but sailing in Pennsylvania is NOT like sailing on the Great Lakes so I don’t do much of that except when I return to Escanaba.

My husband’s family owns a farm outside of Hershey, Pennsylvania, and we live on one end of the farm. This has allowed us to raise our children as outdoor lovers. We also have a beagle (Henry) and several chickens and rabbits. The farm itself is a thoroughbred racehorse farm, operated by my in-laws. We aren’t involved in horse training; instead, we grow grapes. We planted and opened a vineyard and winery in 2008, so that’s our other “hobby”.

Read more:

Preparing To Live With Wolves, By John Vucetich, January 16, 2012, The New York Times

Ecologist Ponders Fairness To Wildlife And The Thoughts Of Moose, By Rachel Duckett, December 21, 2021, Great Lakes Echo

What Wolves Tell Us about Our Relationship with Nature, by Marc Bekoff Ph.D., October 21, 2021, Psychology Today

Isle Royale Winter Study: Good Year for Wolves, Tough One for Moose, by Cyndi Perkins, August 24, 2022 Michigan Tech News