Paul van Susante, Assistant Professor, Mechanical Engineering—Engineering Mechanics talks about MINE, the Multiplanetary INnovation Enterprise team at Michigan Tech, along with electrical engineering majors Brenda Wilson and Gabe Allis; and mechanical engineering major Parker Bradshaw.

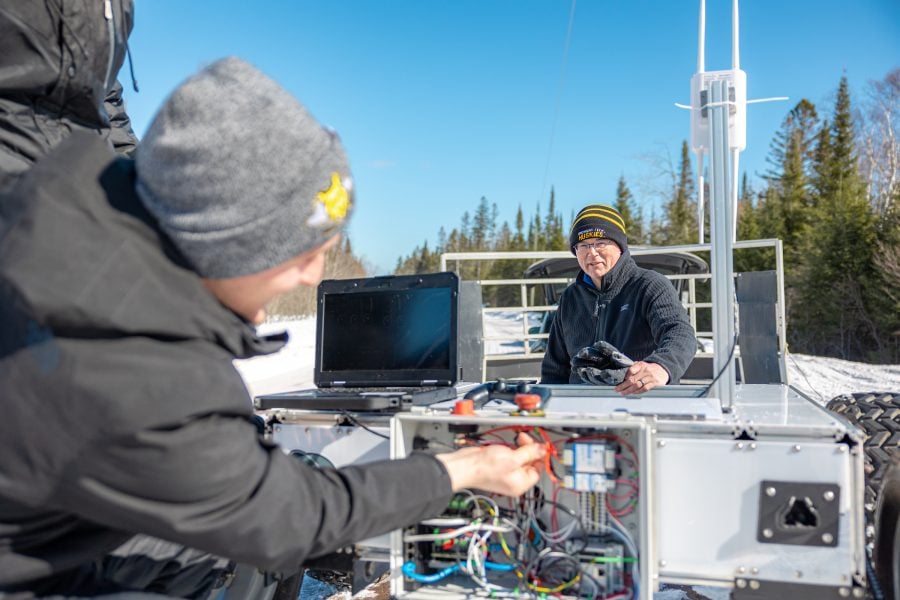

Wilson, Allis and Bradshaw—along with about 50 other student members of the MINE team—design, test, and implement robotic technologies for extracting (and using) local resources in extreme environments. That includes Lunar and Martian surfaces, and flooded subterranean environments here on Earth. Prof. van Susante helped launch the team, and serves as MINE’s faculty advisor.

The award-winning Enterprise Program at Michigan Tech involves students—of any major—working in teams on real projects, with real clients. Michigan Tech currently has 26 different Enterprise teams on campus, working to pioneer solutions, invent products, and provide services.

“As an engineer, I’m an optimist. We can invent things that allow us to do things that now seem impossible.”

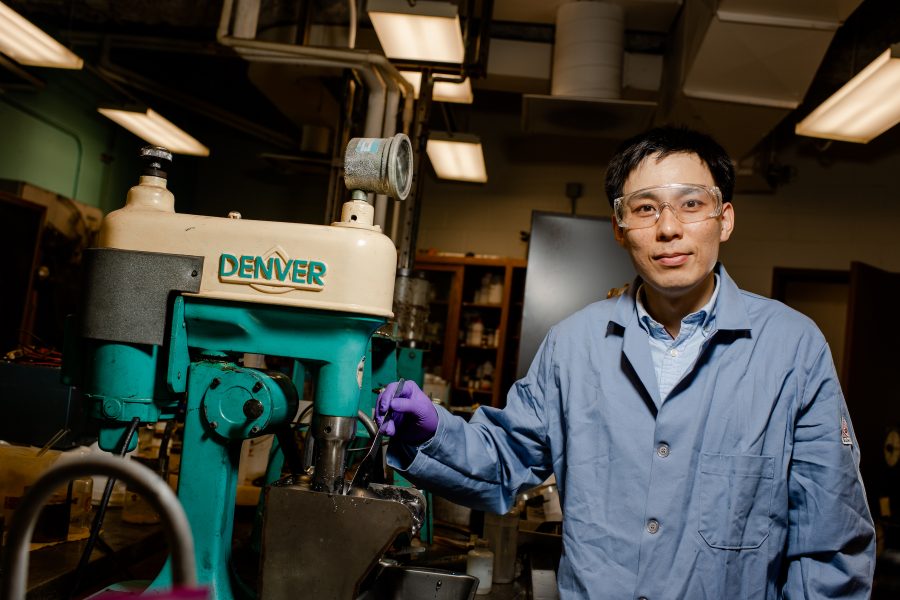

MINE team members build and test robotic vehicles and technologies for clients in government and the private sector. They tackle construction and materials characterization, too. It all happens in van Susante’s Planetary Surface Technology Development Lab (PSTDL) at Michigan Tech, a place where science fiction becomes reality via prototyping, building, testing—and increasing the technology readiness and level of tech being developed for NASA missions. The PSTDL is also known as Huskyworks.

Prior to coming to Michigan Tech, Prof. van Susante earned his PhD and taught at the Colorado School of Mines, and also served as a NASA Faculty Fellow. He has been involved in research projects collaborating with Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, SpaceX, TransAstra, DARPA, NASA Kennedy Space Center, JPL, Bechtel, Caterpillar, and many others.

Prof. van Susante created the Huskyworks Dusty Thermal Vacuum Chamber himself, using his new faculty startup funding. It’s a vacuum-sealed room, partially filled with a simulated lunar dust that can be cooled to minus 196 degrees Celsius and heated to 150 degrees Celsius—essentially, a simulated moon environment. In the chamber, researchers can test surface exploration systems (i.e., rovers) in a box containing up to 3,000 pounds of regolith simulant. It’s about as close to moon conditions as one can get on Earth.

The NASA Artemis program aims to send astronauts back to the moon by 2025 and establish a permanent human presence. Building the necessary infrastructure to complete this task potentially requires an abundance of resources because of the high cost of launching supplies from Earth.

“An unavoidable obstacle of space travel is what NASA calls the ‘Space Gear Ratio’, where in order to send one package into space, you need nearly 450 times that package’s mass in expensive rocket fuel to send it into space,” notes van Susante. “In order to establish a long-term presence on other planets and moons, we need to be able to effectively acquire the resources around us, known as in-situ-resource utilization, or ISRU.”

“NASA has several inter-university competitions that align with their goals for their up-and-coming Artemis Missions,” adds van Susante.

Huskyworks and MINE have numerous Artemis irons in the fire, plus other research projects, too. We’ll learn a lot more about them during Husky Bites.

LUNABOTICS

Electrical engineering undergraduate student Brenda Wilson serves as the hardware sub-team lead of the Astro-Huskies, a group of 25 students within MINE who work on an autonomous mining rover as part of NASA’s Lunabotics competition. It’s held every year in Florida at the Kennedy Space Center with 50 teams in attendance from universities across the nation. This is the Astro-Huskies’ third year participating in the competition, coming up in May 2023.

This year the Astro-Huskies are designing, building, testing, and competing with an autonomous excavation rover. The rover must traverse around obstacles such as mounds, craters, rocks; excavate ice to be used for the production of rocket fuel, then return to the collection point. By demonstrating their rover, each team in the competition contributes ideas to NASA’s future missions to operate on and start producing consumables on the lunar surface.

DIVER

Mechanical engineering undergraduate student Gabe Allis is manager of the MINE team’s DIVER project (Deep Investigation Vehicle for Energy Resources). The team is focused on building an untethered ROV capable of descending down into the Quincy mine to map the flooded tunnels and collect water samples. The team supports ongoing research at Michigan Tech that aims to convert flooded mine shafts into giant batteries, or Pumped Underground Storage for Hydropower (PUSH) facilities.

“Before a mine can be converted into a PUSH facility it must be inspected, and most mines are far deeper than can be explored by a conventional diver,”Allis explains.

“This is where we come in, with a robust, deep-diving robot that’s designed for an environment more unforgiving than the expanse of outer space, and that includes enormous external pressure, no communication, and no recovery if something goes wrong,” he says.

“Differences in water temperature at different depths cause currents that can pull our robot in changing directions,” adds Allis. “No GPS means that our robot may have to localize from its environment, which means more computing power, and more space, weight, energy consumption, and cooling requirements. These are the sort of problems that our team needs to tackle.”

TRENCHER

During Husky Bites, Bradshaw will tell us about the team’s Trencher project, which aims to provide proof-of-concept for extracting the lunar surface using a bucket ladder-style excavator. “Bucket ladders offer a continuous method of excavation that can transport a large amount of material with minimal electricity, an important consideration for operations on the moon,” Bradshaw says. “With bucket ladders NASA will be able to extract icy regolith to create rocket fuel on the moon and have a reliable method to shape the lunar surface.” Unlike soil, regolith is inorganic material that has weathered away from the bedrock or rock layer beneath.

Parker Bradshaw, also a mechanical engineering student, is both a member of MINE and member of van Susante’s lab, where he works as an undergraduate researcher. “Dr. van Susante is my boss, PI, and Enterprise advisor. I first worked with him on a MINE project last year, then got hired by his lab (the PSTDL) to do research over the summer.”

Bradshaw is preparing a research paper detailing data the team has gathered while excavating in the lab’s Dusty Thermal Vacuum Chamber, with a goal of sharing what was learned by publishing their results in an academic journal.

“An unavoidable obstacle of space travel is what NASA calls the ‘Space Gear Ratio’, where in order to send one package into orbit around Earth, you need nearly 10 times that package’s mass in expensive rocket fuel to send it into space, and even more for further destinations,” van Susante explains. “So in order to establish a long-term presence on other planets and moons, we need to be able to effectively acquire the resources around us, known as in-situ-resource utilization, or ISRU.”

In the world-class Huskyworks lab (and in the field) van Susante and his team work on a wide variety of projects:

NASA Lunar Surface Technology Research (LuSTR)—a “Percussive Hot Cone Penetrometer and Ground Penetrating Radar for Geotechnical and Volatiles Mapping.”

NASA Breakthrough Innovative and Game Changing (BIG) Idea Challenge 2020—a “Tethered permanently shaded Region EXplorer (T-REX)” delivers power and communication into a PSR, (also known as a Polarimetric Scanning Radiometer).

NASA Watts on the Moon Centennial Challenge—providing power to a water extraction plant PSR located 3 kilometers from the power plant. Michigan Tech is one of seven teams that advanced to Phase 2, Level 2 of the challenge.

NASA ESI Early Stage Innovation—obtaining water from rock gypsum on Mars.

NASA Break the Ice—the latest centennial challenge from NASA, to develop technologies aiding in the sustained presence on the Moon.

NASA NextSTEP BAA ISRU, track 3—”RedWater: Extraction of Water from Mars’ Ice Deposits” (subcontract from principal investigator Honeybee Robotics).

NASA GCD MRE—Providing a regolith feeder and transportation system for the MRE reactor

HOPLITE—a modular robotic system that enables the field testing of ISRU technologies.

Dr. van Susante, how did you first get into engineering? What sparked your interest?

Helping people and making the world a better place with technology and the dream of space exploration. My interest came from sci-fi books and movies and seeing what people can accomplish when they work together.

Hometown and Hobbies?

I grew up in The Netherlands and got my MS in Civil Engineering from TU-Delft before coming to the USA to continue grad school. I met my wife in Colorado and have one 8 year old son. The rest of my family is still in The Netherlands. Now I live in Houghton, Michigan, not too far from campus. I love downhill and x-country skiing, reading (mostly sci-fi/fantasy), computer and board games, and photography.

“Dr. van Susante has been a huge help—not just with the technical work, but with the project management side of things. We’ve found it to be one of the biggest hurdles to overcome as a team this past year.”

Brenda, how did you first get into engineering? What sparked your interest?

My dad, who is a packaging engineer, would explain to me how different machines work and how different things are made. My interest in electrical engineering began with the realization that power is the backbone to today’s society. Nearly everything we use runs on electricity. I wanted to be able to understand the large complex system that we depend so heavily upon. Also, because I have a passion for the great outdoors, I want to take my degree in a direction where I can help push the power industry towards green energy and more efficient systems.

Hometown, family?

My hometown is Naperville, Illinois. I have one younger brother starting his first year at Illinois State in general business. My Dad is a retired packaging engineer with a degree from Michigan State, and my mom is an accountant with a masters degree from the University of Chicago.

Any hobbies? Pets? What do you like to do in your spare time?

I am an extremely active person and try to spend as much time as I can outside camping and on the trails. I also spend a good chunk of my time running along the portage waterfront, swing dancing, and just recently picked up mountain biking.

“I got involved in the DIVER project in MINE, and have enjoyed working with Dr. van Susante. He’s a no nonsense kind of guy. He tells you what you need to improve on, and then helps you get there.”

Gabe, how did you first get into engineering? What sparked your interest?

I first became interested in engineering when my great-uncle gave me a college text-book of his on engineering: Electric Circuits and Machines, by Eugene Lister. I must have been at most 13. To my own surprise, I began reading it and found it interesting. Ever since then I’ve been looking for ways to learn more.

Hometown, family?

I’m from Ann Arbor, Michigan, the oldest of nine. First in my family to go to Tech, and probably not the last.

Any hobbies? Pets? What do you like to do in your spare time?

I like to play guitar, read fiction, mountain bike, explore nature, and hang out/worship at St. Albert the Great Catholic Church.

“Doing both Enterprise work and research under Dr. van Susante has been a very valuable experience. I expect to continue working in his orbit through the rest of my undergrad degree.”

Parker, how did you first get into engineering? What sparked your interest?

I was first introduced to engineering by my dad, who manufactured scientific equipment for the University of Michigan Psychology department. Hanging around in his machine shop at a young age made me really want to work with my hands. What I do as a member of MINE is actually very similar to what my dad did at the U of M. I create research equipment that we use to obtain the data we need for our research, just for me it’s space applications (instead of rodent brains).

Hometown, family?

I grew up in Ann Arbor Michigan, and both of my parents work for the University of Michigan Psychology department. My dad is now retired.

Any hobbies? Pets? What do you like to do in your spare time?

I have a variety of things to keep me busy when school isn’t too overbearing. I go to the Copper Country Community Art Center Clay Co-Op as often as I can to throw pottery on the wheel. I also enjoy watercolor painting animals in a scientific illustration style. Over the summer I was working on my V22 style RC plane project.