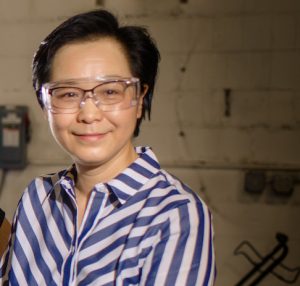

Michigan Tech electrical engineering alumna Dr. Sarah Rajala is professor emeritus and former dean of engineering at Iowa State University. She’s an internationally-known leader in the field of engineering education—and a pioneering ground breaker for women in engineering. She serves as a role model for young women and is passionate about diversity of thought and culture, especially in a college environment.

This month we celebrate with Dr. Rajala—she was elected to the National Academy of Engineering, one of the highest professional recognitions in engineering.

Dr. Rajala, how did Michigan Tech prepare you as a leader in engineering education? Or simply as a leader?

Being the only female in my electrical engineering class, I experienced numerous gender biases. In the early 1970s, there was still much skepticism about whether ‘a girl could be an engineer’. My experiences laid a foundation for my commitment to creating a more inclusive culture in engineering and in engineering education, in general.

You have kept busy, pushing the boundaries across your entire career. What advice do you have for mid-career people looking for their next challenges and opportunities?

First, take advantage of the opportunities that are offered, especially if they allow you to expand your boundaries. Don’t be shy about raising your hand and indicating your interest. Professional societies are great places to find new challenges and opportunities. Of course, it is also important to set your priorities and know when to say no. Also keep in mind that there is no single path that is right for everyone.

Based on what you’ve learned as an educator, do you have one or two pieces of advice for a high school junior or senior?

We each learn new material in different ways. Don’t decide you dislike a subject because you don’t like the way the teacher presents the material. And don’t be afraid to ask questions or ask the teacher if she/he can present the topic differently. Alternatively, work with your fellow students or another teacher who can help you explore the topic in a different way. Search the internet. There are many good resources out there that can supplement what you are learning in class. Take ownership of your learning!

What qualities do students need to develop in themselves in order to become solvers of problems?

Start with the fundamentals. Be inquisitive. Write down what you know and try to start working the problem. If you are really stuck, ask for help. Show someone what you have done so far, then ask for a hint to help you get started. You will learn more, if you can get started and work the rest out for yourself.

Where do you think engineering education will be 20 years from now?

I hope we are more inclusive! No matter how one learns, we should be able to adapt our instructional approaches to engage and motivate everyone. Technology will likely play a larger role in the learning process. There will be an increasing number of new subjects to learn. Students and educators will all need to adapt to new ways to teach and learn.