It’s been a busy fall semester for the Archives. Nine individual classes have incorporated archival sources into their coursework this semester, which means at least 200 students were regulars in the reading room over the past 15 weeks, studying different aspects of the University’s history, such as broomball, the Pep Band, and the Ford Forestry Center, as well as poring through civic and mining company records in search of documentation on the Quincy Smelter, the lives of copper miners, the history of the St. Mary’s Falls Ship Canal Company.

Although the semester is winding down, we’re still seeing last minute student researchers making a final effort to uncover more content or verify source citation information. (Find help citing archival sources at our web pages http://www.lib.mtu.edu/mtuarchives/citation.aspx.)

In addition to the normal bustle of our well-used reading room, the Archives recently played host to a photo shoot.

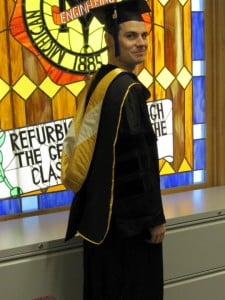

Photographer Calvin Goh (UMC) used the Archives Reading Room as a fitting backdrop for his images of recent graduate, Cameron Hartnell, PhD, Industrial Archaeology. Here, the photographer is captured at his craft:

Cameron’s doctoral research focused on the archaeological remains of the Arctic Coal Company on the island of Spitsbergen, or Svalbard. An earlier Tech grad, Scott Turner, spent six years in the early 20th century working for the ACC at Spitsbergen.

Through his doctoral research, Hartnell became quite familiar with the Scott Turner Collection, housed here at the Michigan Tech Archives. To honor the man whose papers were invaluable to his own research, Hartnell approached the Archives with a unique request: to wear Turner’s doctoral hood in the University’s midwinter commencement ceremonies.

Turner wore this hood when he received an honorary PhD from Michigan Tech in 1932 and it was donated to the Michigan Tech Archives along with corporate records, personal correspondence and other artifacts by Turner’s family following his death. According to Hartnell, the intricate folds and pockets of the graduation hood served a very practical purpose in the past. Students at one time kept a bit of bread or fruit in the pouches so they could continue their studies while they ate.

The following overview on Turner’s life and accomplishments is excerpted from an article by Erik Nordberg, first published in the Michigan Tech Alumnus, 2002.

Scott Turner began his mining career in a somewhat ordinary manner, completing his BS and Engineer of Mines degrees at the Michigan College of Mines in 1904 at the age of 24. A native of Lansing, he had completed an associate’s degree at Ann Arbor before taking up the mining trade as his life’s passion. Yet from these humble Michigan roots, numerous mining jobs and work as an assistant editor for the Mining & Scientific Press took him to the four corners of the globe within the first few years of his career.

In 1926, he received a call from the United States government requesting his service as Director of the Bureau of Mines. Although an important federal appointment, many noted its added significance under then-Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, one of the nation’s most prominent mining engineers. Turner spent eight years at the helm of the BOM, overseeing difficult changes associated with the stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing onset of the Great Depression. During this period, Turner returned to Houghton to receive an honorary Doctor of Engineering degree in 1932. He received similar honorary degrees from the University of Michigan, Colorado School of Mines, and Kenyon College.

A chance meeting with John Longyear in London in 1911 directed a major change in Turner’s career. The Marquette, Michigan, lumber and mining man was interested in potentially profitable iron and coal deposits in Spitsbergen, an unclaimed arctic island north of Scandinavia. Turner accepted the position of manager for Longyear’s European interests, an assignment that would keep his attention focused on Spitsbergen for nearly six years. In addition to a “small fixed annual salary,” he received a bonus of 5% of the company’s net profits.

His work in Spitsbergen was marked by many unusual feats. The mines proved particularly difficult to develop; only 750 miles below the North Pole, the Arctic Coal Company was the first company to successfully implement modern mining methods at so high a latitude. In addition, the land was “terra nullius,” meaning that no single nation had ownership of the place. Through permission of the U.S. government, Turner represented American interests in the region – perhaps the only time that a civilian engineer has been enlisted to maintain American sovereignty overseas.

It was on one of Turner’s many trips across to Spitsbergen that he became a participant in another of history’s infamous incidents. On May 7, 1915, as it neared the coast of Ireland, a German torpedo struck Turner’s ship, the S.S. Lusitania, just a few decks below the engineer’s cabin.

The mining engineer’s work continued in earnest. Following his discharge from the hospital, he continued his journey to Scandinavia and arranged for the sale of Longyear’s Spitsbergen properties to Norwegian interests (on his trip from England to Norway, his ship narrowly missed destruction by bombs dropped from raiding German Zeppelins). Looking to escape the growing European turmoil, Turner headed south, pursuing work in Peru, Chile and Bolivia. He completed a two-year stint in the Naval Reserves at the tail end of World War I and then spent the next seven years of his life as “Technical Head” for the Mining Corporation of Canada. This work took him to various parts of that country – as well as China, Mexico, Russia and South America — on exploratory and mine development work. He often traveled with his new wife, the former Amy Pudden, whom he had married in Lansing in 1919.

Following his departure from the Bureau, he pursued a variety of consulting work. At one point he was an officer or director of nine mining companies. He even returned to Spitsbergen to review the progress of mines he developed decades earlier. His life work was capped in 1957 when he received the Hoover Medal, a special honor commemorating civic and humanitarian achievements of engineers. Recipients are selected by a special board with representatives from the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), the American Institute of Chemical Engineers (AIChE), the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) and the American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical and Petroleum Engineers (AIME).

Scott Turner died in July 1972, just one day shy of his 92 birthday. In his later years, when not hunting or fishing, Turner would talk regularly of his life’s adventures. But it was his spot on the Lusitania that always singled him out for the most attention. He responded to endless requests for interviews and completed dozens of questionnaires about the incident. In the mid-1950s Turner donated the Boddy life belt that had saved his life to the museum at Michigan State University. It is not clear what became of a cast iron medal he owned, minted in 1915 by the German government to celebrate the sinking of the Lusitania. The medal had been uncovered during some road construction in Washington, D.C. and had been presented to Turner as a survivor of this historic event.

The staff of the Michigan Tech Archives congratulate Cameron Hartnell on his achievement and are pleased that our collections – both paper and fabric – were such integral parts of his study and graduation.