At the Michigan Technological University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections, summer means genealogy! Taking advantage of our warmer weather and the local attractions open for the season, visitors arrive from all around the country–and even the globe–to research their family history. In turn, our staff members learn more about the people who called this place home years ago and their family connections.

The love of genealogy that these visitors display is part of a long tradition in the United States. From America’s earliest days, tracing family ties or handing down family stories has been a hobby for some and a calling for others–and Houghton County was no exception. In 1917, students from Houghton High School and the upper grades of nearby primary schools were asked to write short essays about their families, with an emphasis on ancestors, their origins, and any particularly intriguing anecdotes. What the students produced ranged from terse, straightforward accounts to colorful stories apparently penned by budding novelists. Compiled by the Keweenaw Historical Society and presently part of that organization’s collection (MS-043), the essays recount ancestors with origins in places as diverse as Germany, Finland, Ukraine, and Syria.

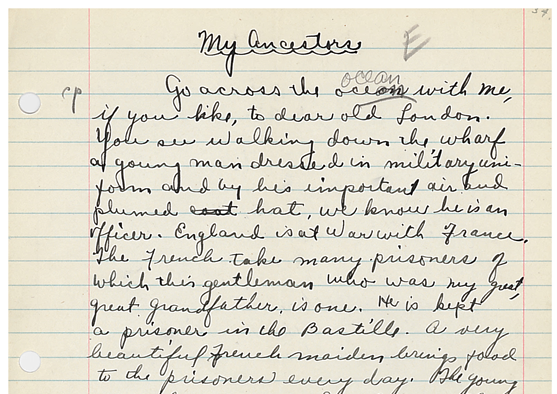

Despite differences in origin, the stories demonstrate many common themes. Students boasted, wherever possible, of illustrious ancestors and connections to fame. Strobel claimed that one of her relatives had traveled to America with his close friend, a brother of Charles Dickens. Claribel Wright took pride in her “pure English stock”; she asserted that she was descended from a Mayflower passenger and had cousins in famous businesswoman Hetty Green and women’s rights activist Susan B. Anthony. Ruth Standish MacDonald did Claribel’s Mayflower ancestor one better: her middle name came from Miles Standish, one of the most famous of these Pilgrims and Ruth’s earliest known family member. Other pupils described forefathers who had made good in their home countries: Joseph Strobel bragged of one who had received “the Sword of Honor” from a German emperor, for example, while Mary Piipponen had no small admiration for her grandfather, who had personally petitioned the Tsar of Russia to restore the Finnish constitution.

But even more typical to the students’ essays were stories of challenges and tragedies, ones that prompted emigration to the United States or that continued to stalk families after their arrival. Fred Caspary’s family, after immigrating from Germany, took a homestead near Puget Sound. “Then,” he said, “the railroad came… and my parents had to sell after living on it 9 years 9 months.” Embarrassed, Harold Gross admitted that his father’s family had neglected to snuff out all the candles after a night of partying and caused a fire that killed eleven people. James Finley recalled that his twenty-year-old grandfather left Ireland after his mother starved to death during the Irish Potato Famine; he traveled only with a younger brother, just twelve years of age. Myrtle Brassaw, writing of her mother’s journey from England to America in the 1860s, described “a terrible disease”–cholera–that “arose among the people, taking the lives of two hundred ten.” Another Myrtle, Myrtle Warrington, had lost a grandfather to the Osceola Mine fire of 1895.

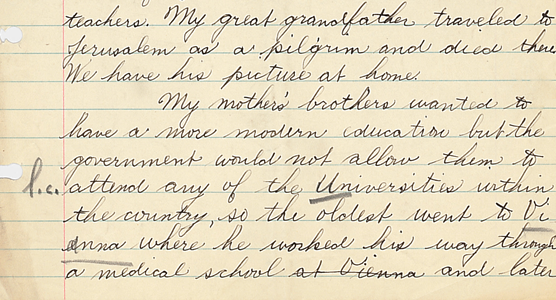

In hindsight, perhaps the most distressing paper was that written by high school student Sadie Kremen, documenting the lives of the Kremen and Futran families. These ancestors came from the Odessa region of Ukraine, wrote Sadie, who noted proudly that all of her mother’s male relatives “were learned men or teachers.” Her uncles, as young men, were so dedicated to learning that they “wanted to have a more modern education but the government would not allow them to attend any of the universities within the country.” The Futran family, like the Kremen family, were Jewish, and the Russian Empire, which ruled Ukraine, had closed many doors to Jews. Sadie’s uncle found opportunity in Vienna and Berlin; he trained as a physician in both cities before returning home and offering his services to Russia during World War I. “Although the government through its admirable educational system,” Sadie said incisively, ”had not permitted him to study within the country, they were very glad to have the services of a trained doctor.” Sadie’s paternal aunts and uncles had encountered similar prejudice from the government in the later years of the 19th century. “Finding the persecution and tyranny of the government unbearable,” they decamped to America, and her parents soon followed. A little over twenty years after Sadie wrote her essay, Ukraine would be caught up in the Holocaust; over 800,000 Ukrainian Jews were killed, a number that undoubtedly included members of Sadie’s extended family.

I cannot let this blog post go by without mentioning a personal discovery in the collection: an essay penned by Ethel Moyle, my great-grandmother. She wrote this piece in eighth grade, the last year of school she attended. I never had the chance to know Ethel, but her paper tells me that she might have been an imaginative young lady–or raised by parents determined to pull the wool over her eyes. “My father’s father was a sailor in a boat for a good many years,” she said. “One day they had a wreck and he was drowned.” In reality, her paternal grandfather had suffered a fatal injury while working as a miner. On the other hand, Ethel explained that her maternal grandfather “died a long time ago, when my mother was a baby. After, my grandmother and mother decided to come to America.” Ethel’s mother had more motivation to misremember her family history: she had been illegitimate, possibly the result of an assault on her mother. Then, as now, it seems that descendants were motivated to remember their predecessors in the best–and most interesting–light.

Perhaps, as I did, you will discover an ancestor’s essay tucked away in the Keweenaw Historical Society Collection. Maybe you will discover a compelling or tragic story that needs to be shared; you might enjoy a memory passed down through the generations. If nothing else, the prose of these young student-authors stands firm on its own merits, more than a century after it was put to paper.

By Emily Riippa, Assistant Archivist